ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several people helped in creating this book. I would like to thank Lori Andersen for her work, especially on compiling the resources. I would also like to thank Natalie Dudnytska for her assistance with the chapter summaries. I would like to thank Dr. Jennifer Cross for her editing work and ideas shared throughout the process. And I would like to thank Lacy Compton for her work editing this book.

I thank Joel McIntosh for supporting this project, knowing that it would likely appeal to a relatively small readership.

DEDICATION

I would like to dedicate this book to Ben and his familyRoger, Sherry, and Amanda.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

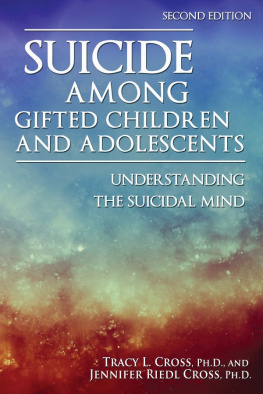

Dr. Tracy L. Cross holds an endowed chair, Jody and Layton Smith Professor of Psychology and Gifted Education, and is the Executive Director of the Center for Gifted Education at The College of William and Mary. Previously he served Ball State University as the George and Frances Ball Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Gifted Studies, the founder and Executive Director of both the Center for Gifted Studies and Talent Development, and the Institute for Research on the Psychology of the Gifted Students. He has published more than 150 articles, book chapters, and columns; made more than 200 presentations at conferences, and has published six books. He has edited four journals in the field of gifted studies (Gifted Child Quarterly, Roeper Review, Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, Research Briefs) and is the current editor of the Journal for the Education of the Gifted. He received the Distinguished Scholar Award in 2011 from the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC), and the Distinguished Service Award from both The Association for the Gifted (TAG) and NAGC. He also received the Early Leader and Early Scholar Awards from NAGC and in 2009 was given the Lifetime Achievement Award from the MENSA Education and Research Foundation. In 2004, he was named the Outstanding Researcher for Ball State University. He serves as the President-Elect of the National Association for Gifted Children.

In addition to an active scholarly agenda, for 9 years he served as the Executive Director of the Indiana Academy for Science, Mathematics and Humanities, a residential high school for intellectually gifted adolescents. He has served as director of two state associations for gifted (Wyoming Association for Gifted Education and Indiana Association for the Gifted). He also served as president of TAG and on the Board and Executive Committee of the NAGC. He will become the President of the National Association for Gifted Children on September 1, 2013.

He lives in Williamsburg, VA, with his wife, Dr. Jennifer Riedl Cross, four children (Ian, Keenan, Colin, Eva) and Bob, the English bulldog.

CHAPTER 4

SUICIDE TRAJECTORY MODEL AND PSYCHACHE

In my understanding of the various theories associated with suicide, I have come to prefer two: Stillion and McDowells (1996) suicide trajectory model and Schneidmans (1993) psychache. These two models resonate with my professional experience of suicide and seem to provide considerable explanatory power about suicidal behavior.

SUICIDE TRAJECTORY MODEL

Stillion and McDowell (1996) developed a theory-based model of suicide called the suicide trajectory model (STM; see ), which includes associated risk factors. The emphasis of the theory is to predict risk for suicidal behavior.

Suicide Trajectory Model Categories and Associated Risk Factors

| Category | Risk Factors |

| Biological | Gender (male) Race (Native American, White) Genetic bases (parental psychopathy) Sexual orientation (homosexual, bisexual) Serotonin dysfunction |

| Psychological | Low self-esteem Depressed mood Feelings of hopelessness/helplessness Aggressive-impulsive tendencies Poor coping strategies Existential questions |

| Cognitive | Poor social problem solving Inflexible thinking Negative self-talk Rigidity of thought |

| Environmental | Familial dysfunction (Impaired parent-child relationships) Social isolation Stressful life circumstances (interpersonal loss) Presence of lethal methods Exposure to suicide completers (friends/family) |

The STM groups correlates of suicide into four categories (biological, psychological, cognitive, and environmental) that provide considerable breadth. This makes conceptual understanding of the numerous predictors of suicide in a theoretical manner manageable. It provides a conception of suicide that offers professionals numerous handles upon which to grasp as they try to prevent deaths. Metaphorically, it provides a categorical system of potential weights that lead the potentially suicidal person in the direction of suicide. The theory attempts to tie together the categories of factors in a coherent manner. Stillion and McDowell (1996) stated:

As we move through life, we encounter situations and events that add their weight to each risk factor category. When the combined weight of these risk factors reaches the point where coping skills are threatened with collapse, suicidal ideation is born. Once present, suicidal ideation seems to feed upon itself. It may be exhibited in warning signs and may be intensified by trigger events. In the final analysis, however, when the suicide attempt is made, it occurs because of the contributions of the four risk categories. (p. 21)

The limitation to the STM, however, is that it is largely made up of correlations or variables associated with suicidal behavior with limited influence from within the person. This is where Schneidmans (1993) work picks up as he moves the conversation from descriptive epidemiology and prediction with some explanation, to a theory that has been empirically validated focusing on the subjective experiences of the suicidal person. I believe this to be the most important contribution to research on the suicidal mind.

PSYCHACHE

I never thought Id die alone

I laughed the loudest whod have known?

I trace the cord back to the wall

No wonder it was never plugged in at all

I took my time, I hurried up

The choice was mine, I didnt think enough

Im too depressed to go on

Youll be sorry when Im gone

Adams Song by Blink 182

Edwin Schneidman was a clinical psychologist and arguably the father of suicidology and thantology (the study of death and the care of the dying) in the U.S. He died in 2009. He spent his career focused on suicide, authoring 20 books and numerous articles about suicide, including one wherein he focused on survivors of suicide1998s The Suicidal Mind. This book provides considerable information about the lived experience of suicide attempters: one of the three died, the second lived for several months before dying of infections, and the third survived but was disfigured by the attempt. Schneidman began the American Association of Suicidology and the journal Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. He also coined the term psychological autopsy.

Psychological autopsy, while often used to determine equivocal deaths, has become an invaluable approach to studying the life of a person who completed suicide. My colleagues and I employed this approach in our early research (Cross, Cook, & Dixon, 1996) and again later (Cross, Gust-Brey, & Ball, 2004). From his many years in the field working with clients, and from previous research, Schneidmans (1993) theory asserted that suicide attempts come from the desire on the part of the person to escape intolerable psychological pain. He called this pain psychache. This profound pains etiology includes several potential pathways and factors. Ultimately, when the pain is unbearable, suicide becomes the path to escape from the pain.

Next page