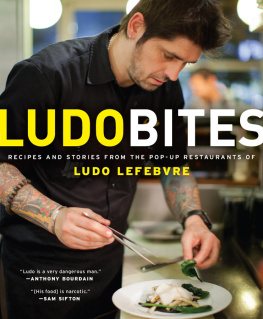

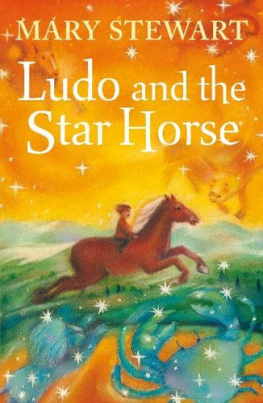

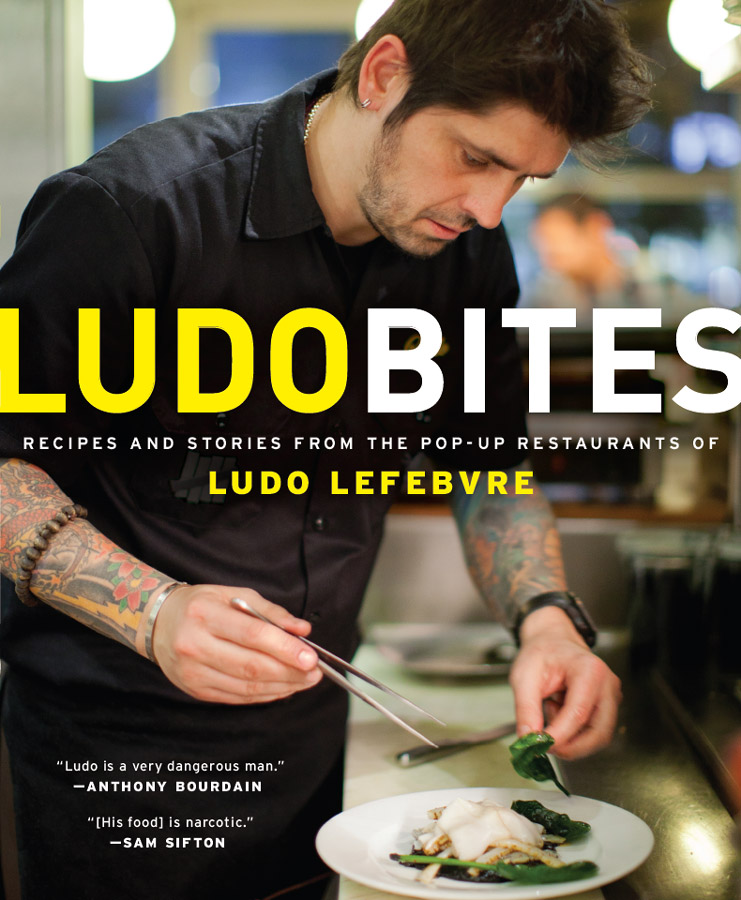

LUDOBITES

RECIPES AND STORIES FROM THE POP-UP RESTAURANTS OF

LUDO LEFEBVRE

WITH JJ GOODE AND KRISSY LEFEBVRE

For Krissy, Rve, and Luca

Contents

Colin Young-Wolff

Colin Young-Wolff

Shayla Deluy

Colin Young-Wolff; painting by Matt Scofield

Its 3 P.M. on a hot September afternoon and the Closed sign has just gone up at Gram & Papas, a breakfast-and-lunch spot owned by my friend Mike Ilic in the heart of downtown Los Angeless fashion district. There are still a few customersa business guy powering through a turkey burger and, over by the window, two women with poached tuna salads who have been talking about their boyfriends since I came in an hour ago. All of a sudden, the griddle hisses and froths as one of the Gram & Papas cooks pours on water and scrubs away the burger grease in full view of the last diners. The cleanup cant wait: a transformation is about to happen. Before the lunching women can gather their purses, a new restaurantmy restaurantwill inhabit this space, as if by magic.

Already my cooks, squeezed into a back prep area, are hard at work, cutting Cantal cheese into batons, frying chicken skin, roasting a pigs head. Wearing black T-shirts with a chefs-knife-wielding rooster on the front and the words Just Make It Happen on the back, my crew is eager to take over the kitchen and do some serious cooking, as soon as the guys in army-green Gram & Papas T-shirts clear out the plastic forks and wipe the mayonnaise smears from the glass partitions. Soon my fresh waitstaff, also in black, will arrive to fold white cloth napkins, light votive candles, and set out the silverware. My wife, Krissy, has that dont-bother-me look as she answers an e-mail plea on her laptop from a big-shot begging for a last-minute tablethree months ago, most of the restaurants seats were snapped up in a thirty-second burst of Internet insanity on OpenTable.

In less than three hours, Ive got 110 people coming for dinner, and I still havent decided what to do with the oxtail broth bubbling away on the stove. Plus the brioche still needs something. Maybe four-spice powder?

Grace! Wheres the four-spice?

Upstairs, chef!

I need it, Grace... now !

Oui, chef. Right away, chef!

Welcome to LudoBites .

I am a chef with a restaurant that has no permanent address, and thus no permanent place to keep the four-spice powder. In order to cook my food, I rely on the kindness of friends or friendly strangers who have a kitchen and dining room to spare. I usually appear for two or three months at a time, always at night.

I like to think of myself as a painter doing exhibitions in different locations. Each new dish I create is another piece of my art, often inspired by the place where Im cooking. My latest exhibition is LudoBites 007, and tonight Gram & Papas is my restaurant. But tomorrow it will belong again to Mike and the sandwich-eating lunch crowd, with barely a sign that I was ever there. That is how the pop-up game is played.

Some people call me the king of pop-ups. Jonathan Gold, the Pulitzer-Prize-winning restaurant critic at the L.A. Times , compared me to a roaming DJ and wrote that what Im doing is revolutionary. In his New York Times review of my cooking, Sam Sifton said, Every plate is a fully realized piece of art. LudoBites has been called a phenomenon, a revolution in dining. I love the way that sounds, but all I know for sure is that LudoBites was an accident.

I was just barely a teenager when I traveled from my home in Auxerre, France, in Burgundy, to the village of Saint-Pre-sous-Vzelay. I was there to work, without pay, at LEsprance, the three-Michelin-star restaurant run by Marc Meneau. From there, I moved 200 miles south to work for Pierre Gagnaire, and then to Paris to work for Alain Passard at LArpge and for Guy Martin at Le Grand Vfour, all of them demanding chefs with small armies of highly trained, meticulous cooks bustling in kitchens with walk-ins bigger than my first apartment. The chefs treated me like the lowly cook I was, rebuking me for my long hair and for showing up to work in a T-shirt. Chef Gagnaire took a shine to me, but he still had me doing prep work for two years before trusting me at the stove. Like all French chefs that came before me, I gradually learned from seemingly eternal repetition and starting at the bottom as a kid.

In 1996, I came to the United States eager to prove myself as the chef de partie at LOrangerie , L.A.s most famed French restaurant. Within a few short months, the chef left unexpectedly, and to my surprise I was promoted to executive chef. After six and a half years at LOrangerie, the owner of the legendary Bastide restaurant asked me to come cook provocative avant-garde food. I eagerly took him up on the challenge, believing that because I enjoyed creating this elaborate, aggressive cuisine, it was what I was meant to cook.

Six weeks after Bastide received a Mobil five-star rating in 2005, its owner, Joe Pytka, decided to close for a couple of months to redesign the space. It was an odd decision. After being there for a year and a half, I finally felt like we had an amazing team in the kitchen. And people were finally starting to get my avant-garde food, which, let me tell you, was nothing like L.A. had ever seen.

Most of the time, my job at Bastide was like a fantasy. Joe treated me well and was extremely generous. I had a great salary, an incredible kitchen, and a huge staff. For my birthday, for Christs sake, he bought me a $15,000 Ducati motorcycle. When the restaurant was temporarily closed, Joe and I ate our way through Europe, flying on his private jet to five countries in seven days. On the way over there, we spent just enough time in New York City to eat a lavish lunch at Jean Georges before boarding the plane to make our reservation at Heston Blumenthals the Fat Duck, outside of London, the next day. Then we were off to San Sebastin, in Spanish Basque country, for a day of incredible pintxos , the Basque version of tapas, and dinner at Mugaritz, to eat the food of Andoni Aduriz, whod come from elBulli. Next we hit Venice, where we ate at, among other restaurants, Harrys Bar, where the bow-tied, white-jacketed waiters brought out plates and plates of simple, delicious food. Now, keep in mind that this trip was barely even planned in advance. Joes assistant called me three days before we left, asking if I had a passport. Sure, why? I asked. Because, she said, were all going to Europe to do some research.

Our dream trip had ended on a strange, sour note. To make a long story short, we stopped in Bangor, Maine, to refuel on our way back to L.A. There, customs officers searched the jet and found my prescription meds (I hate flying). Because Id only found out about the trip days before we left, I took medication we had at home that had been prescribed to Krissy. Having what appeared to be drugs that werent prescribed to you, I found out, is a no-no, especially when youre a foreigner. I was interrogated, strip-searched, and threatened with jail and deportation. In the end, everything worked out, but when I look back on it, I see that as a foreshadowing of what was to come.

Next page