Gardening with Heirloom Seeds

2006 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Arnhem and Bickham types by Eric M. Brooks

Manufactured in China

This book was published with the assistance of the Blythe Family Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Coulter, Lynn.

Gardening with heirloom seeds: tried-and-true flowers, fruits,

and vegetables for a new generation / by Lynn Coulter.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8078-3011-6 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8078-3011-9 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8078-5680-2 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8078-5680-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Seeds. 2. Vegetable gardening. 3. Flower gardening.

4. Fruit-culture. I. Title.

SB117.C74 2006

635dc22 2005031389

cloth 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1

paper 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1

To Bill

Like Muir, a

mountain-dweller

With thanks to

Michael for the

love and chocolate

chip cookies

In memory of

James and Juanita

Baxter

Contents

Acknowledgments

Gardeners are generous people. The seeds they sow produce a bounty of flowers and vegetables that others can enjoy. In that tradition of sharing, many people have contributed to this project. I am sincerely grateful for the wonderful images, seed packets, seeds, and gardening expertise provided by the following heirloom gardeners, photographers, and seed sellers. Thank you all for your gracious help and support.

Marilyn Barlow, of Select Seeds

Professor David W. Bradshaw, Department of Horticulture, Clemson University

David Cavagnaro, of David Cavagnaro Photography

John Coykendall, heirloom gardener

Wesley Greene, garden historian, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Renee Shepherd, of Renees Garden Seeds

Aaron Whaley, Diane Whealy, and Kent Whealy, of Seed Savers Exchange

Text from William Curtiss Botanical Magazine is courtesy of the National

Agricultural Library, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Heartfelt thanks to Roseanne Key for her friendship and encouragement.

Gardening with Heirloom Seeds

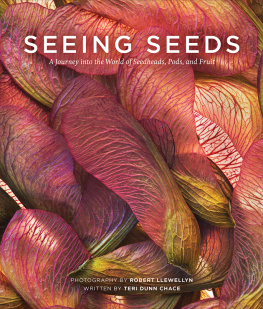

A Celebration of Seeds

There are heirloom seeds asleep in my refrigerator, tucked into brown paper envelopes wound with rubber bands. They have been there since last fall, when I collected them from my garden and dropped them into the crisper alongside some shriveled radishes. Id almost forgotten them until I heard the rumble of a neighbors rototiller and suddenly realized its time to plant.

Theres a science to seed keeping, but Im a laid-back kind of gardener who doesnt stress over it. For me, its enough that a farmer at a roadside stand gives me a sandwich bag filled with ebony seeds and promises they will grow the sweetest melons I ever put in my mouth. I dont mind driving around to find a deserted house Ive passed just once before, when some starry yellow blossoms were beginning to open in a patch of weeds. In the fall, when the blossoms fade, I will return and shred them for their ripened seeds. Keeping seeds this waydumping them into baggies and stuffing them into pocketsmay seem slightly disrespectful, especially when you consider what Im keeping. Heirloom seeds are much more than the promise of next summers crookneck squash or mammoth sunflowers. They are living antiques, handed down from one generation to another. They are an inheritance of flavor or beauty from long ago and, often, far away.

Heirloom seeds have proved to be excellent travelers through time and space. I can expect the old-timey turnips I will plant this year to have the same rosy skin and sweet flesh as the ones my grandmother grew behind her Depression-era rental house in South Georgia. Once my scarlet runner beans are up, their brilliant red flowers will lure just as many thirsty hummingbirds as Thomas Jeffersons did when he grew the beans at Monticello in 1812. Some heirlooms, of course, have been around even longer. You cant get out of elementary school without learning that corn was an important native crop. Early peoples were already cultivating its ancestor, mahiz, when Columbus stepped onto their shores. Exotic amaranths, with their dangling ropes of red, purple, and chartreuse flowers, were known in ancient Greece. Julius Caesars troops carried cabbages with them when they marched into Britain in 55 B.C. Two Englishmen were among the most influential early plant collectors and distributors. John Gerard, gardener to one of Queen Elizabeths advisors, described many new discoveries in his 1597 Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes. John Parkinson, apothecary for James I, cataloged other botanical finds in his 1629 Paradisi in Sole, Paradisus Terrestris.

Eventually, heirloom seeds traveled in the other direction. Immigrants pouring into the New World often carried with them seeds from their cottage gardens, fields, and vegetable patches so they could continue to enjoy the flowers they had always grown or satisfy their cravings for familiar foods in a strange and different land. Many seeds were smuggled in, hidden under suitcase linings and hatbands or sewn into dress seams to avoid confiscation by sharp-eyed officials. There are even stories of tiny lettuce and tomato seeds being glued to the backs of postage stamps and mailed from behind the Iron Curtain on letters bound for America.

Over time, all this seed saving has changed. What started as a quest for previously unknown species or new varieties has become a way to remember our ancestors or native lands. More and more, we are saving seeds as a link to the past.

Luckily, Iowa gardener Diane Whealy saved her own green heritage before it disappeared. Whealys great-grandparents were Bavarian immigrants who sailed to America in 1867, bringing with them seeds from the morning glories they had grown around their European home. Their son (and Whealys grandfather) Baptist John Ott kept the flowers going. Whealy remembers visiting his Iowa farm, sitting beside him on a porch draped in a curtain of velvety purple blossoms with heart-shaped leaves. On one visit, Grandpa Ott gave Whealy and her husband, Kent, a small bottle of morning glory seeds and the seeds of his favorite tomato, German Pink. Grandpa Ott died soon after their trip, and Diane realized the seeds would have been lost if she had not taken them. There would have been no one left to tend the morning glories and tomatoes, no left to save more seeds.

The Whealys decided to share the flower seeds, now christened Grandpa Otts morning glory, with other gardeners who loved old plants. Interest in antique varieties started to spread, and by 1975 the Whealys efforts had blossomed into the Seed Savers Exchange of Decorah, Iowa. To date, the nonprofit organization has preserved an astounding 24,000 varieties of vegetables, fruits, and grains. Its network of more than 10,000 members allows gardeners from all over the world to trade their antique seeds. An offshoot group, the Flower and Herb Exchange, links some 3,000 gardeners equally devoted to old-timey varieties.

If you are wondering exactly what an heirloom seed is or how old a plant has to be before it is considered an antique, the answer is a little tricky. Is that battered cedar chest your aunt left you really an antique, or just old? Most gardeners agree that a plant becomes an heirloom when its been around longer than fifty years, while others set the bar at a century. But others dont hold to a strict definition. Why not include the chili plant your dad brought out of his native Mexico some forty-odd years ago, as long as you love the fiery bite of the peppers and you think of him when you plant the seeds? Its not just the age of that old chest that makes it valuable; its also where it came from and who gave it to you.

Next page