The Last Panther

The Breakout from the Halbe Kessel

April-May 1945

Wolfgang Faust

Translated from the memoir

Kesselpanzer

(Cauldron Panzer)

By Wolfgang Faust

Copyright The Estate of Wolfgang Faust

This Edition Published Globally 2015

Bayern Classic Publications

Translated and Edited by Sprech Media

All rights are reserved, including resale,

quotation and excerpt, in part or whole, in all languages.

This is not a public domain text in any part.

The German terms Koenigstiger and Ritterkreuz have been translated as

King Tiger and Iron Cross respectively. While not exact translations,

these are the most widely recognised English terms.

Where appropriate, other German terms are explained in brackets in the text.

Contents

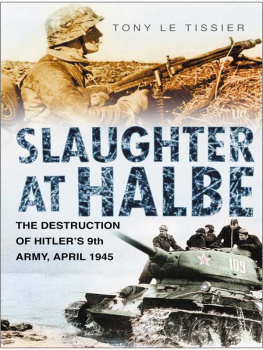

Editors Introduction

While the apocalyptic struggle for Berlin in 1945 has been extensively discussed by historians, the massive battle of the Halbe Kessel (which took place at the same time) has received less attention. In late April 1945, the entire German Ninth Army was encircled by Red Army forces about 30 km south of Berlin, as the Soviets raced onward to the capital. The Ninth Army, which comprised a mix of Wehrmacht, Waffen SS and ad-hoc units, totalling some 80,000 men, became trapped in a Kessel (cauldron or pocket) around a town named Halbe in the Spree Forest. Among them were a large number of civilian refugees, predominantly women and children, fleeing the Soviet advance.

For the German civilians, fear of Soviet occupation was huge: partly a result of Nazi propaganda about Red monsters, but also stemming from knowledge of Red Army crimes against women during the advance. For the troops, there was the fear that capture by the Soviets would lead to deportation to the Soviet Gulag system, in which survival was believed to be only a remote possibility. For both the soldiers and civilians in the Kessel, therefore, escaping and surrendering to the Americans (and not the encircling Soviets) became a desperate priority.

The Ninth Army managed to break out of the Kessel through Halbe, amid scenes of carnage which even veteran troops described as the worst they had witnessed. In a series of splinter groups, fighting vicious but confused battles, the breakout troops and civilians fought through Red Army lines to link up with the German Twelfth Army, who had opened a corridor to them to from the American front in the South West. A few thousand exhausted survivors of the Ninth finally crossed the River Elbe in the closing days of the war, and achieved their goal of surrendering to the Americans; the others were killed or captured by the Soviets.

Among these escapees of the Halbe Kessel was the young Wolfgang Faust, commander of a Panther tank with the 21 st Panzer Division, who had spearheaded some of the breakout attempts. After the war, Faust wrote about his combat in the Kessel, in a memoir entitled Kesselpanzer, which remained unpublished in his lifetime. We have now edited and translated Kesselpanzer as The Last Panther for readers in English, and we hope that the horrific human story of the Halbe Kessel will reach a new audience as a result.

As with Fausts only other surviving book (Tiger Tracks), this memoir was written with combat still vivid in Fausts mind, and is extremely graphic in its depiction of the final chaotic hours of the Third Reich. Some modern readers may be disturbed by Fausts clinical descriptions of battles, while others will value the remarkable glimpse into the mentality of young German troops who had grown up under the Third Reich. Certainly, The Last Panther gives us insights into a part of the war which has seldom been described by those who were present, and never in such ruthless detail.

While bearing in mind that Fausts world view was rooted in the German mid-twentieth century, and not the sensitivities of the present day, I strongly believe that Fausts two books are a remarkable testament to the catastrophe of 1943-45 for both the Soviets and the Germans. I commend both these memoirs to twenty-first century readers who are seeking to understand the Second World War from all its possible perspectives.

Chris Ziedler

May 2015

The Last Panther

Entering the Kessel

In the spring of 1945, the war that we had provoked with such ambition was closing on us like a trap. In January of that year, I was the driver of a Tiger 1 panzer in our defence of the River Oder. In February, my battalion was smashed apart and my commander, Helmann, was burned to death in his turret. By April, in the intense reorganisations required by our collapse, I was made commander of my own panzer with the 21 st Panzer Division, part of the great German Ninth Army. My panzer was one of the superb Panthers, the pride of the panzer troops. My rank was now Feldwebel ( sergeant ) and I commanded a crew of teenagers, who looked up to me as if I was a veteran at the age of twenty. Our units tried to hold the Red advance back from Berlin. This was impossible, and we were scattered, while the Reds stormed onward to the capital.

In the last week of April, the trap was shut. The Red forces encircled our entire Ninth Army, South of Berlin, and shut us into a zone of forests where we could only conceal our vehicles and wait for orders.

The hiding was a torment. We sat in our panzers and sweated. Inside the Russian encirclement, inside a pine forest, inside a forty-eight tonne Panther. That was when I realised how completely caught I was; crouched on the commanders chair in the turret, sweat pouring down my back and my heart thumping like a jack hammer. The shadows of Russian bombers were flickering through the pine branches overhead, and the sound of the Russian artillery was loud even through the Panthers armour plate.

We were trapped. Locked in by the Russians, who would ship us to Siberia for sure if they captured us. Our only hope was to reach the American lines on the river Elbe to the West for the Americans were our great hope now. They were once our enemy, the destroyers of our cities, but they were now our salvation if we could only reach them. To be a prisoner of the Amis meant hot dogs, cabbage and the Geneva Convention. To be a prisoner of the Reds, we were sure, meant slavery, the Arctic Circle and never seeing your homeland again. But there was an entire Russian army between our battle group and the Americans, between our handful of Panthers, our exhausted Panzergrenadiers and a following of civilian refugees who traipsed behind us, sobbing like a funeral procession.

How long do we have to wait, Herr Feldwebel? my gunner asked me.

The Capo will be back soon, I told him. The Capo will know what to do.

The Capo was our name for our platoon leader, our Leutnant. His original unit of six Panthers was now down to three surviving vehicles, and he was attending an emergency officers briefing to decide our groups next move.

The air in the Panther turret was foul: monoxide exhaust, shell explosive, oil and five big, hunched young men who hadnt washed for weeks, sweating in the heat. I opened my commanders cupola. Light flooded in through the hatch: clear, spring light scented with pine needles. Through a gap in the trees, I could see white clouds way up in the blue sky. In a second, though, the sky was crossed with vapour trails and the red-starred wings of the Russian planes, and the reek of explosive blew in on the warm breeze.

The sheer hopelessness of our situation came home to me then.

Our three Panthers were parked among the pine trunks in a dense area of forest. To our East, we had a thin screen of troops as a rear guard, but the Russians were probing and testing that line, minute by minute. The sound of their tank engines rose and fell on the breeze, and we could hear the exchanges of fire between our boys and the Russian infantry who rode on the Red panzers. We knew from experience that the Russian commanders didnt like entering forests, whether from tactical reasons or some Slavic superstition, and their huge Josef Stalin panzers, machines as big as Tiger 1 panzers, could not manoeuvre or traverse their gun barrels between the trees unless they knew the pathways that we knew.

Next page