KING ARTHUR

Copyright 2018 Nicholas J. Higham

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018953721

ISBN 978-0-300-21092-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Cheryl

CONTENTS

PLATES AND MAPS

Plates

Maps

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

T his book would have been impossible to write without the prodigious amount of scholarly work undertaken by a whole legion of researchers, stretching back to the nineteenth century. It is particularly appropriate in a work dealing with King Arthur to acknowledge the sense in which I have been carried to this point on the shoulders of so many giants of scholarship working in a variety of interrelated disciplines. Arthurian studies has been an extraordinarily prolific area of endeavour over the last century and more, resulting in an exceptional quantity of published work.

Specifically, Martin Ryan very kindly read and commented on most of the chapters presented here in an early draft; as ever, I am extremely grateful to him. My thanks too go to Lindsay Allason-Jones, Frances McIntosh and Paul Bidwell for advice regarding Sarmatian finds along Hadrians Wall, to Peter Schrijver on the origin of the name Arthur, to Paul Fouracre on all matters Frankish and to Charles Insley for various fruitful discussions regarding the Irish Sea region in the early Middle Ages. Patrick Tosteven very kindly provided photographs of material in Ribchester Roman Museum (. Many of my students over the last few decades contributed to my thinking about Arthur by asking questions to which I felt bound to seek answers; to all go my thanks. I am grateful also to Heather McCallum, Marika Lysandrou, Rachael Lonsdale and Samantha Cross at Yale University Press for commissioning this book and for all their assistance along the way, to Jacob Blandy for his skills as copy editor and to Martin Brown for his excellent maps.

Notwithstanding the number and scale of these many debts, all errors are my responsibility alone.

It is to my wife, Cheryl, though, that this book is dedicated, for she has borne the brunt of my preoccupation with Arthur over the decades and has found herself walking with me up hill and down dale to view sites that so often present as just odd piles of stones. For her good humour, patience and encouragement along the way my grateful thanks.

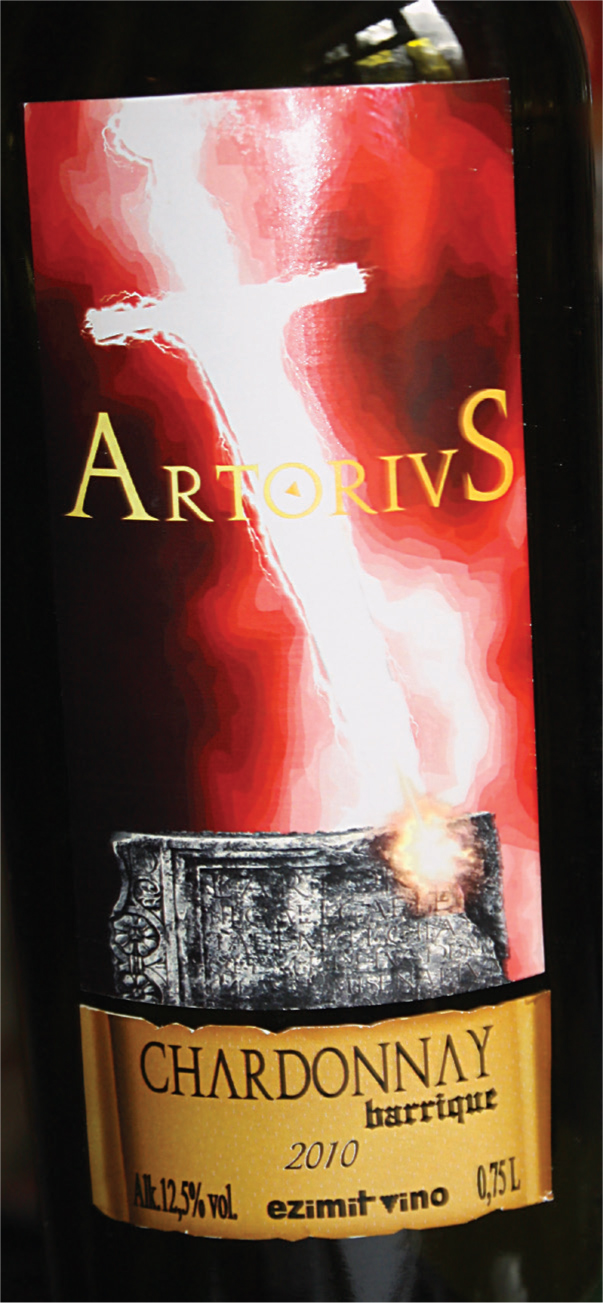

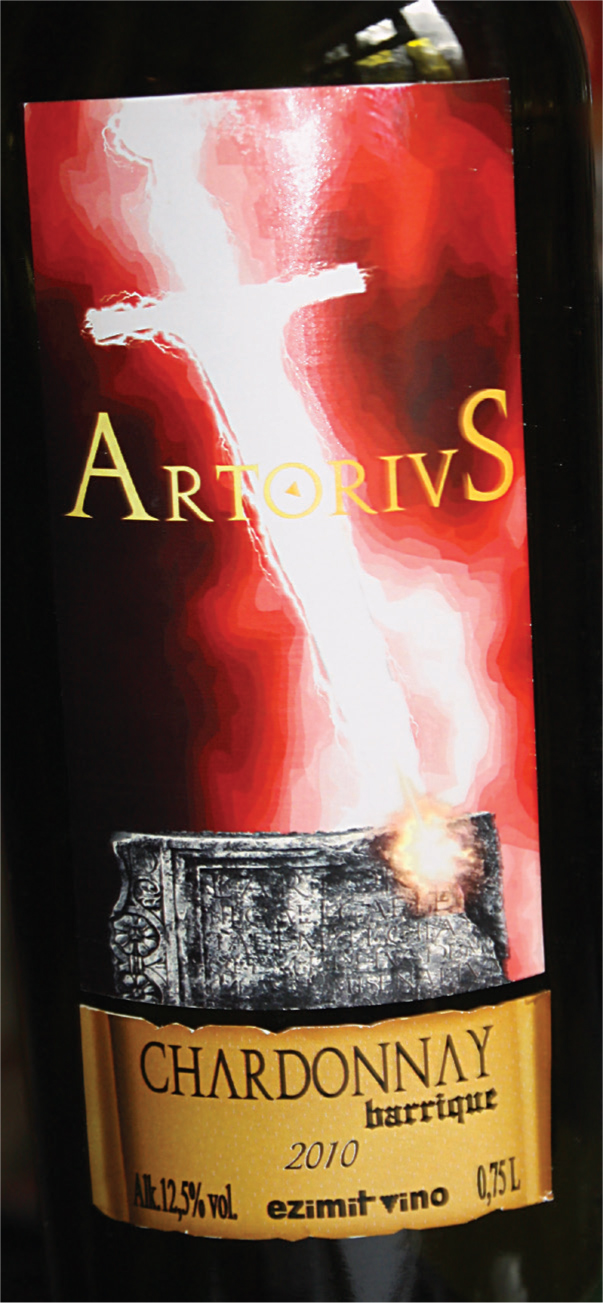

1 A wine label from Podstrana, Croatia, featuring the sword in the stone. The stone depicted is the longer of the Artorius inscriptions (see ).

2 St Martins Church, Podstrana. One of the replica inscribed slabs is visible in the cemetery wall immediately to the left of the church.

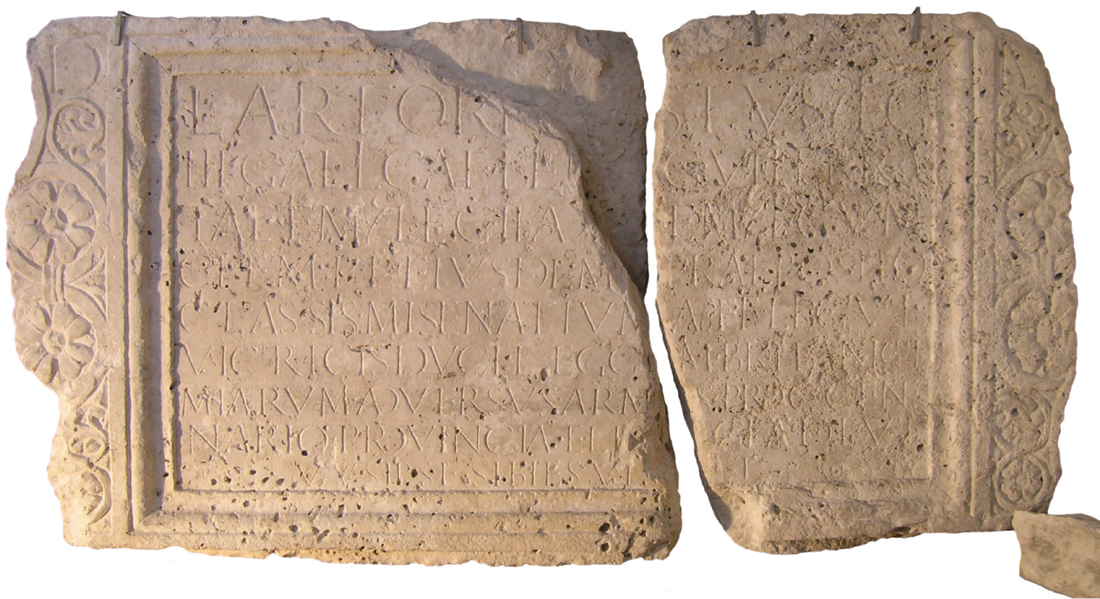

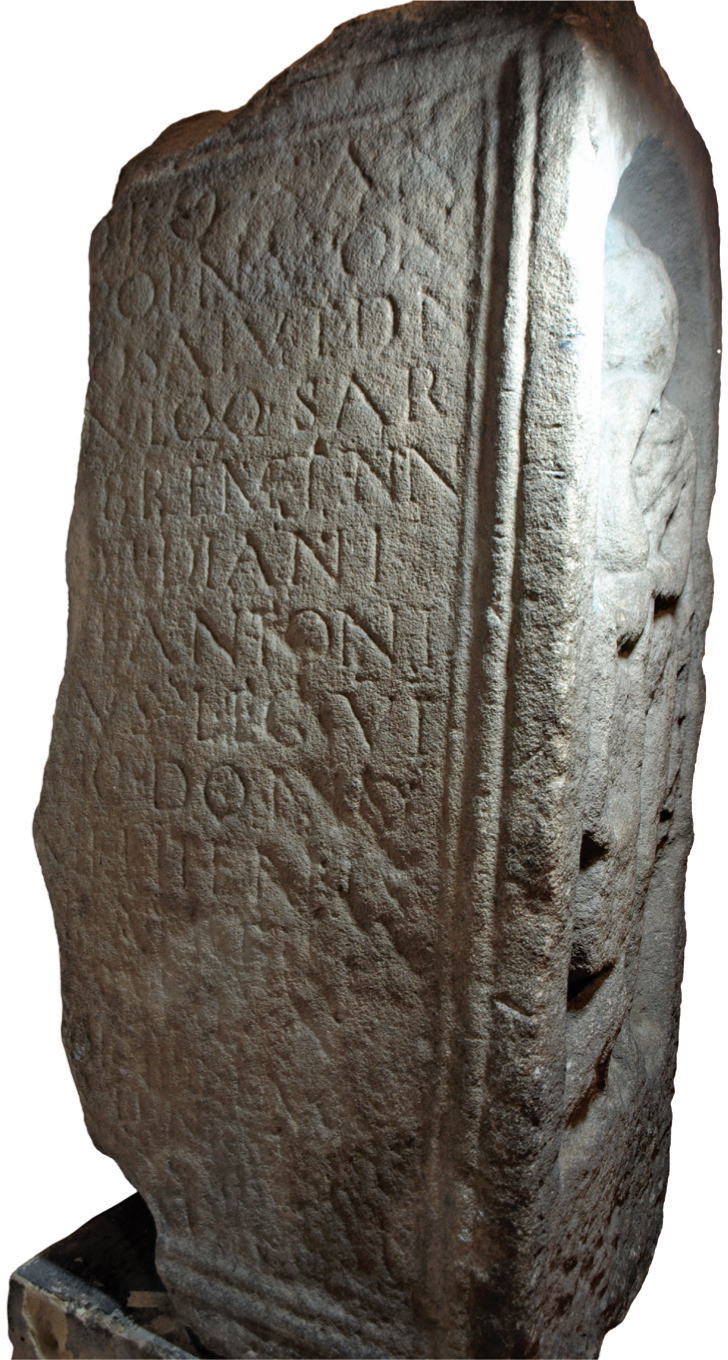

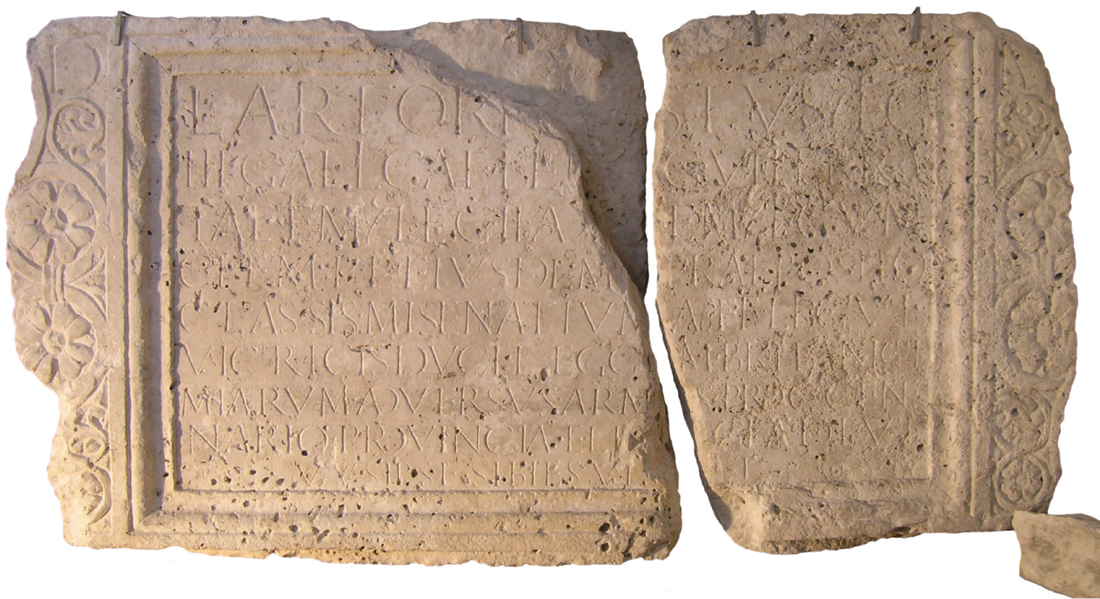

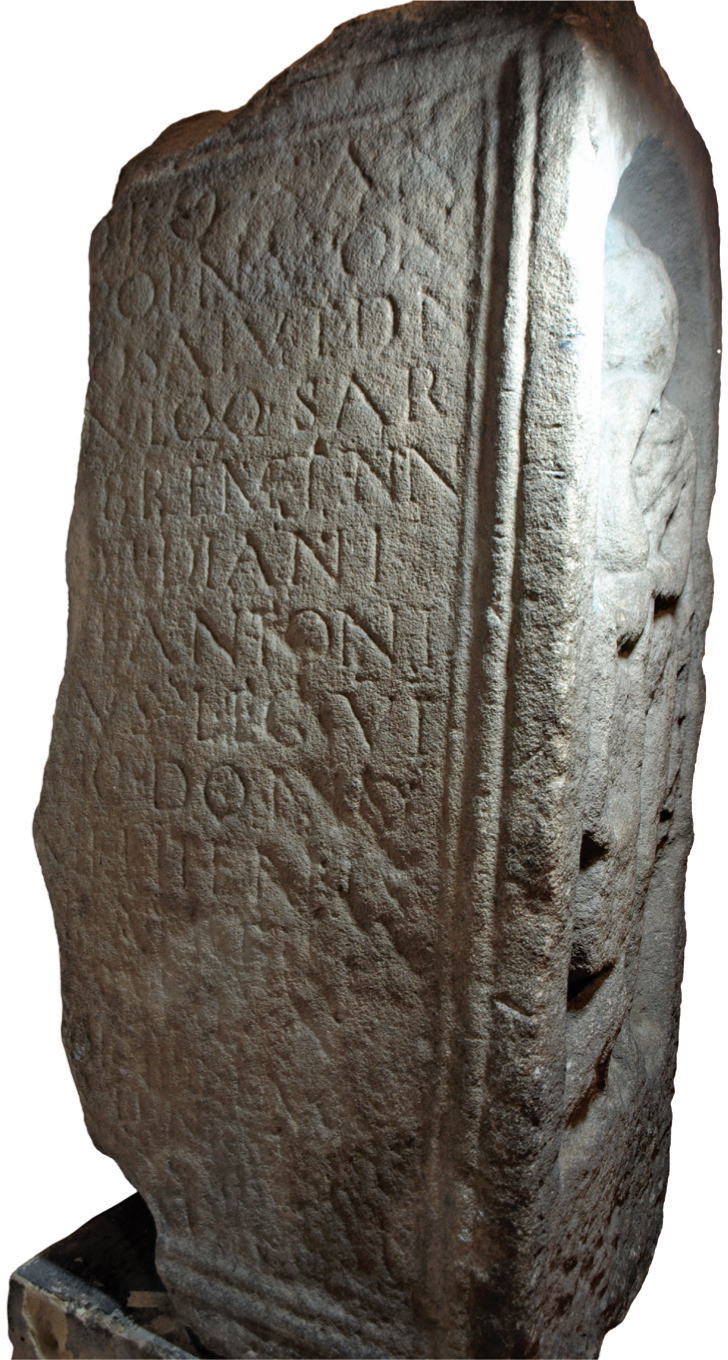

3 The larger Artorius inscription, restored and displayed inside St Martins Church, Podstrana.

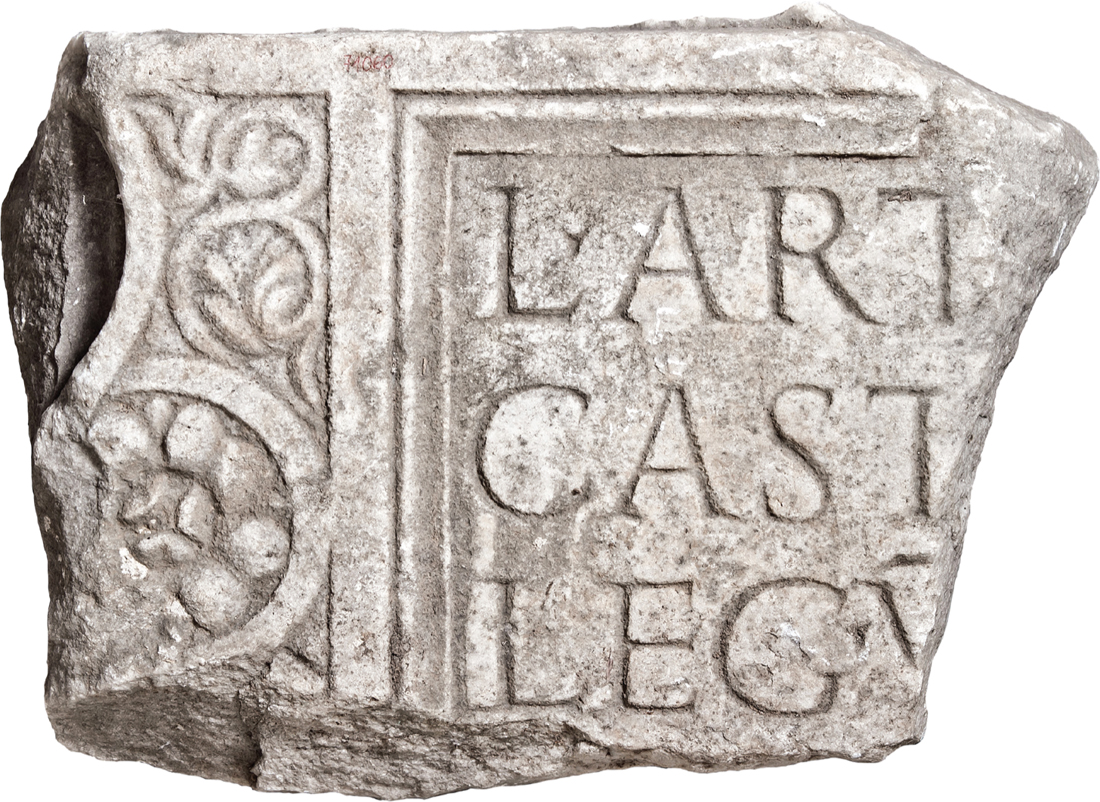

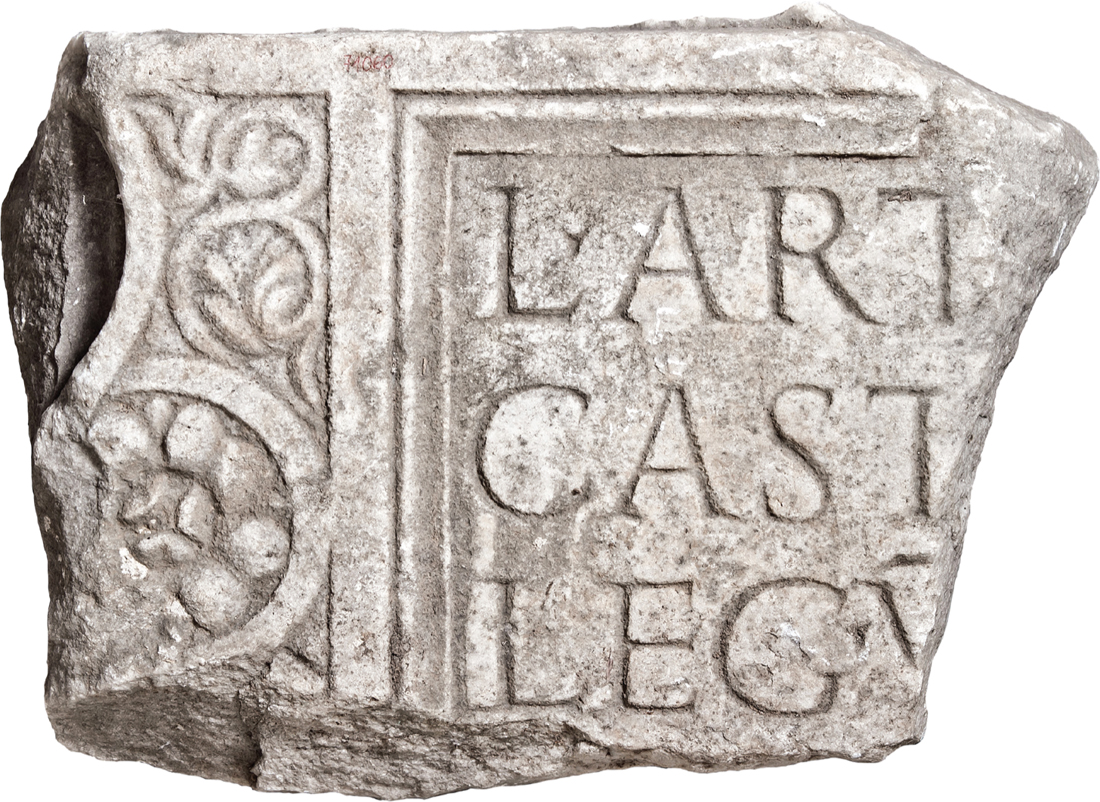

4 One of three pieces of the smaller Artorius inscription that was recently re-identified in the Archaeological Museum of Split.

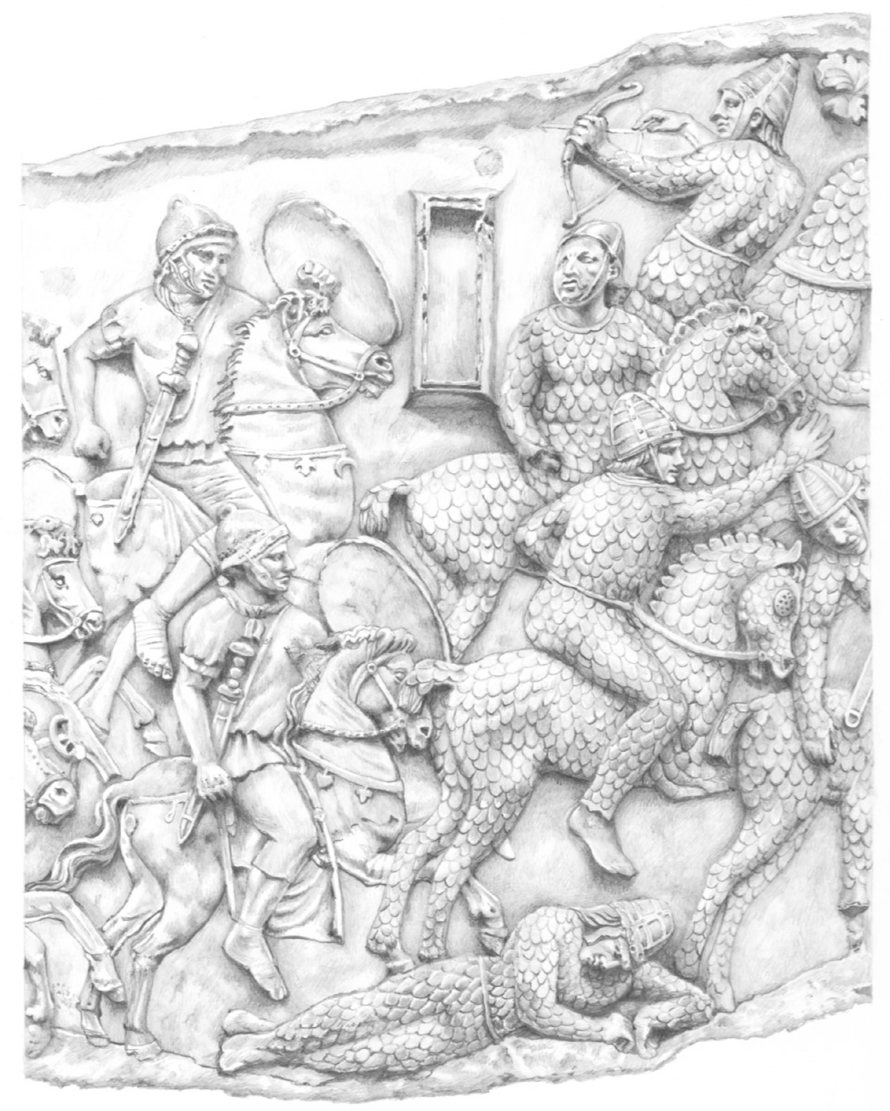

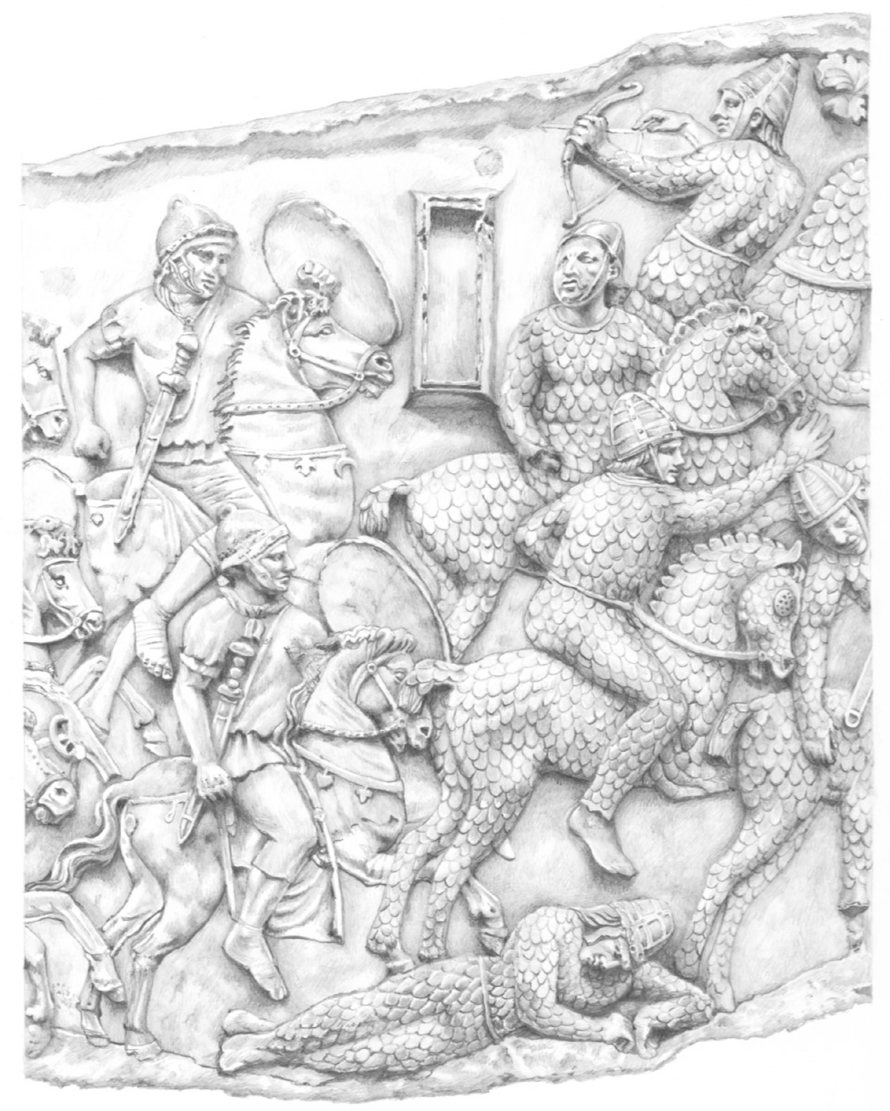

5 A depiction of Sarmatian warriors in flight from Roman cavalry on Trajans Column. This scene provides a near-contemporary vision of Sarmatian equipment, but may not have been particularly accurate in its execution.

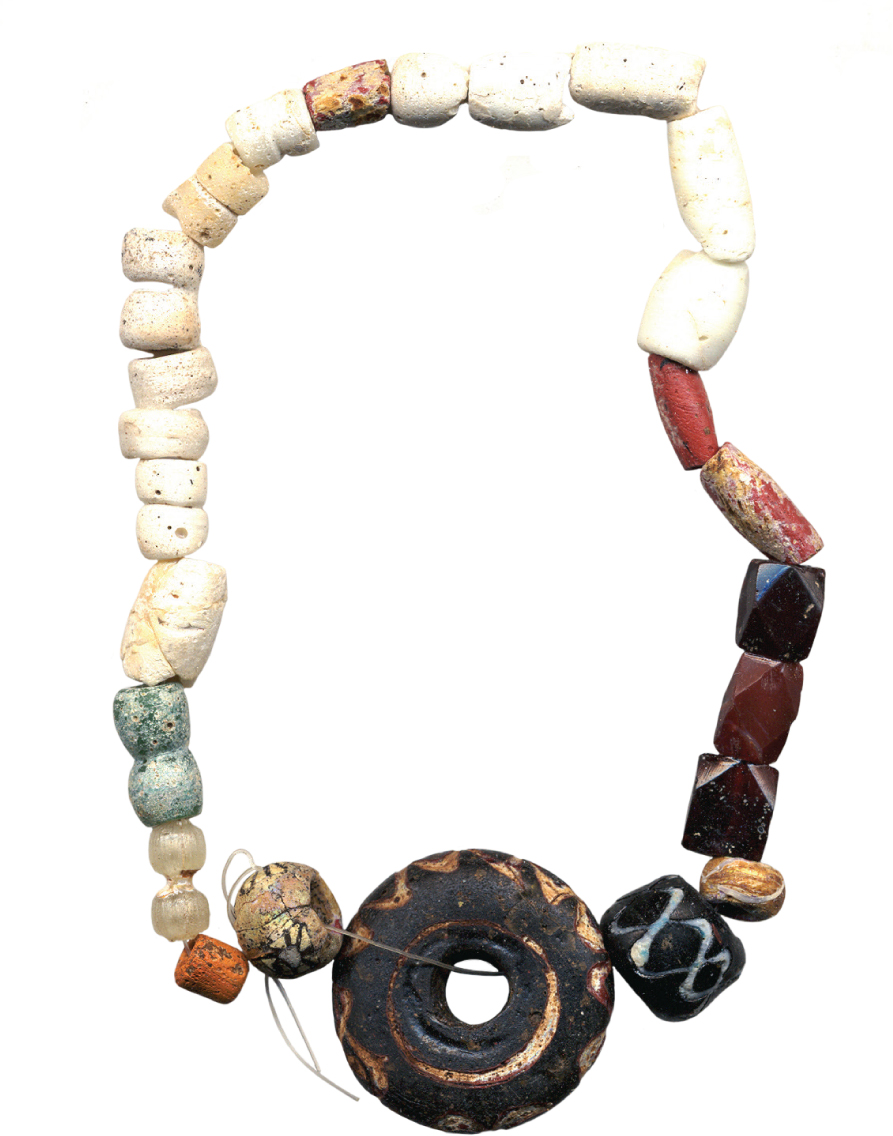

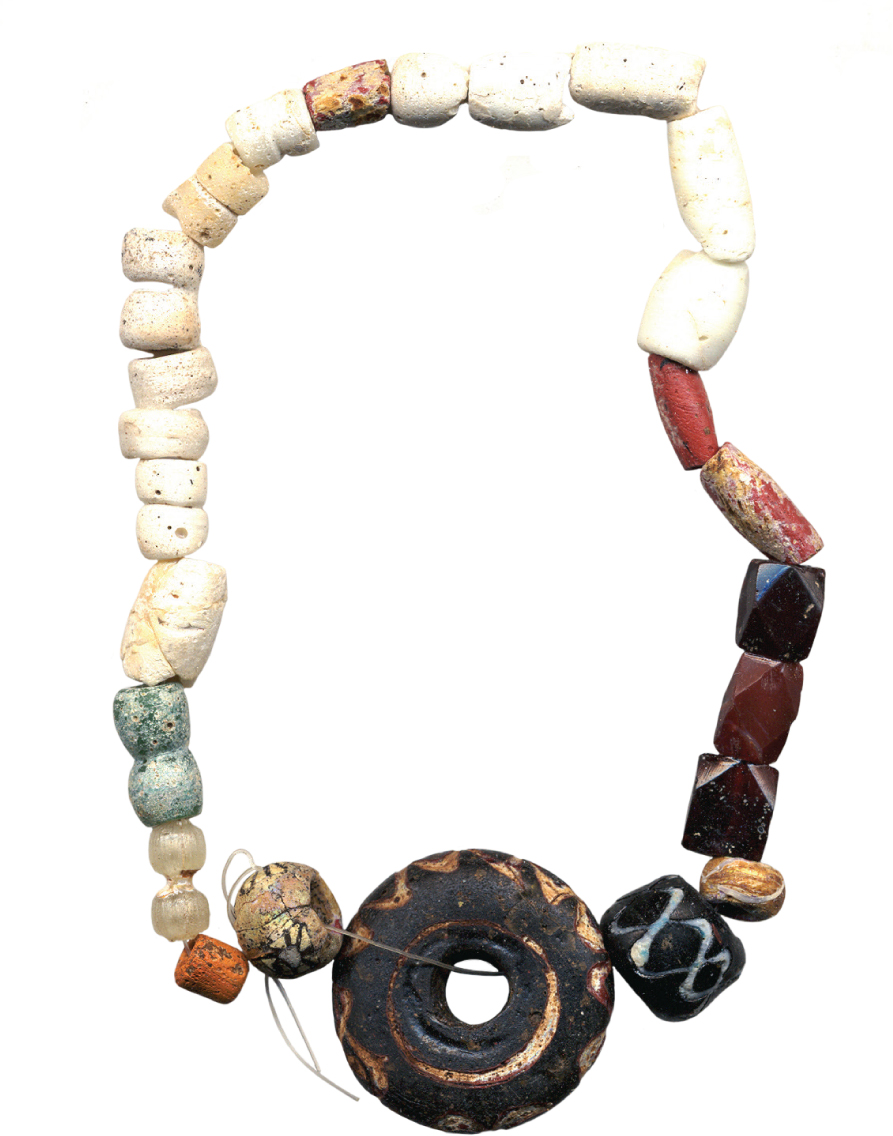

6 Sarmatian beads from Chesters Roman fort on Hadrians Wall: a very rare example of material that has been interpreted as being deposited by Sarmatian warriors serving in Britain.

7 A funerary relief carving of a probable Sarmatian cavalryman found at Chester, perhaps a draconarius serving with the legion stationed there.

8 A lead tamga from Ribchester, which has so far been the sole artefact of probable Sarmatian manufacture that has been found at this, the only cavalry fort in Roman Britain known to have had a Sarmatian garrison.

9 The Apollo monument from Ribchester: the inscription refers to Gordians own unit of Sarmatian cavalry.

10 Three Sarmatian burial mounds at Vaskt, Hungary, reflecting the colonisation of the Carpathian Basin by these Black Sea nomads during the early Principate. No such monuments have ever been found in Britain.

11 Mid-fifth-century Sarmatian pottery from excavations of the brick factory site at Tiszafldvr, in the Tisza valley, Hungary.

12 Sarmatian beads of the mid-fifth century from excavations of the brick factory site at Tiszafldvr.

13 Excavation of the fourth- and fifth-century levels at Ribchester in 2016. Both wall-lines and industrial workings are now being uncovered, comparable to many other Roman fort sites in northern Britain.

14 A stone footprint at the Dl Riatan stronghold of Dunadd (Argyll), which may have been used in ceremonies of royal accession by Scottish kings.

15 A sword-in-the-stone motif features on the late medieval crozier of the archbishop of Siena. This derived from the cult of St Galgano, which developed in the late twelfth century at nearby Montesiepi.

Next page