Contents

The activities in this book require the use of knives, axes and various woodworking and carving tools and should be performed with great care and under adult supervision. Neither the author nor publishers can accept responsibility for any loss, damage or injuries that may occur as a result of these activities, and the author and publishers disclaim as far as the law allows any liability arising directly or indirectly from the use, or misuse, of the information contained in this book.

Introduction

Think of how many times a day you use a spoon. This simple, ordinary tool is a part of our everyday lives, intimately entwined with acts of eating and socialising, from stirring our first cup of coffee to scraping the last bit of pudding from our bowls. And who doesnt like to spoon in bed?

The spoon is the first tool we learn to use as children, and using it transports us back through human history to a time when our lives were very different, but our utensils very much the same. Using a spoon speaks of our evolution as humans, of our graduation from chips of wood the Anglo-Saxon spn through to the beautiful Roman, Scandinavian or Celtic spoons which have inspired some of the designs you will see in this book.

Spoons are really bowls with a handle, which ask to be held, and by better appreciating our relationship with them we make our lives better. One of the things I hope this book will suggest is how much thought goes into creating something so small and apparently insubstantial as a good wooden spoon which requires so very many things to be right to be truly good. We will celebrate the value of the tools we use, of our magnificent landscape and our key resource, the wood itself, and perhaps foremost the actions of the individual maker and his craft processes.

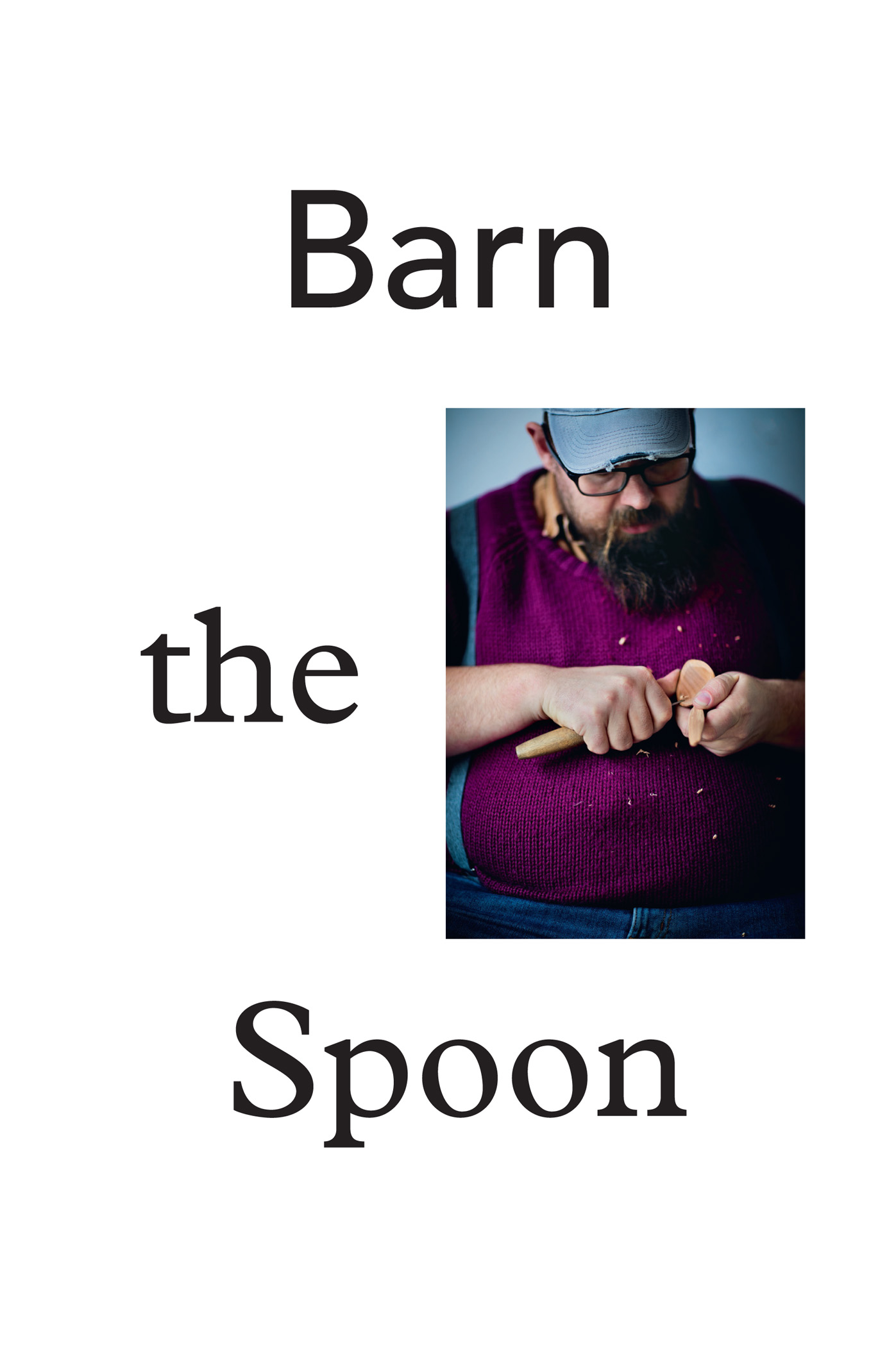

As a craftsperson, spoons are something upon which I have been able to build a life. Creating these small, functional sculptures has allowed me the chance to explore the concept of beauty in three dimensions, and through the process of carving using axes and knives I have discovered how satisfying making functional objects can be. I have now spent many years making spoons. I have lived in forests, learning about wood as it grows; I have been lucky enough to spend time with acknowledged experts in different aspects of woodwork, seeing how they approach their craft. All of this has left me with a great and subtle sense of a green wood movement.

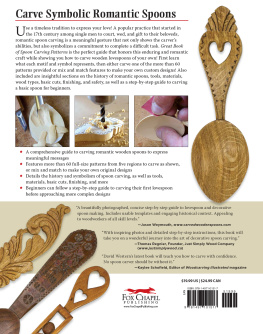

The definition of green wood, and green woodwork, is key to understanding the way that I create spoons. A live tree is 50 per cent water, and green wood differs from this only in so far as it is cut down, so dead, but it is still wet. Knives and axes are the key tools of the green wood worker, as they allow us to efficiently work wet wood into spoons, whereas dry or seasoned planks where the water levels within the wood have reached equilibrium with their environment tend to be worked with more industrial tools, like bandsaws and belt sanders.

Green woodwork is sympathetic to both environment and materials, and quite separate from the industrialised aspects of wood processing which only distances the individual from the tree. Green woodworkers often cut the wood themselves, or source it from tree surgeons, and the relationships we build, and the understanding of woodland practice which we acquire, has a big impact on the way we think about making spoons.

I see spoons as the emblem of, as well as the gateway to, a broader cultural understanding; what has been called a new wood culture or perhaps more appropriately a wood culture renaissance. Both of these terms are about having a holistic approach to woodwork, which includes lifestyle, and about recognising that trees are fundamental to the way we have evolved as human beings. We need them to breathe, of course, but they are also central to our ideas of home and humanity trees have given us everything from the timbers for our houses to the bows and arrows which defined our human ancestors.

The wood culture renaissance is about the rebirth of a way of life which places a sustainable interaction with trees at its centre. For woodworkers like me, its about finding a way of working which takes a step back from machinery and puts forgotten skills back at the heart of making. Being mindful of the way we work deeply affects the physical form of our craft objects, foregrounding questions of provenance and our relationship to things we buy. These issues are pertinent today and run counter to the trend of the last century of industrialised mass production.

People have been using spoons since prehistory, with our earliest ancestors adapting horns, shells or chips of wood to help them eat. The ancient words for spoons suggest this, with the Greek and Latin word derived from cochlea, or spiral shell, and the Anglo-Saxon spn means simply a chip of wood. Virtually all early cultures used wooden spoons to cook with and all developed their own spoon making traditions: the Shang Dynasty in China used spoons made out of bone, while the ancient Egyptians revered the wooden spoon enough to be buried with them.

The earliest known inhabitants of northern Europe were certainly woodworkers: a Neolithic stone axe found at Ehenside tarn in Cumbria is between 5,000 and 6,000 years old. That the Iron Age Celts of Britain used spoons is evidenced by the discovery of a small wooden ladle during excavations at Glastonbury Lake Village. Despite the propensity of wooden artefacts to rot, recent discoveries have shown that Anglo Saxons and Vikings both produced wooden spoons for domestic use.

The process of carving a spoon provides a lens into a historical period when our lives were simpler and more sympathetic to the natural environment than those we lead today. The humble, rural way of life suggested by wooden spoons was largely displaced by our industrial, metropolitan age, and is considered old-fashioned at a time when we are dissatisfied with factory, but not office work at least on the surface of things. A resurgent craft movement, recognising our need to make and do, is surely born out of the knowledge that we are not fulfilled by our sedentary, digital lives. On the fringes, people are beginning to remember the benefits of rural life, and a well-made wooden spoon, like good studio pottery before it, suggests an alternative world away from that which we currently inhabit.

Next page