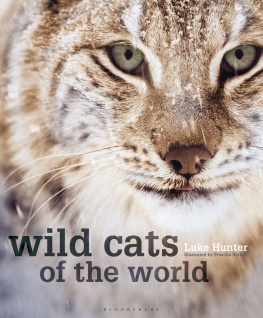

Bloomsbury Natural History

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2015

Luke Hunter, 2015

Illustrations Priscilla Barrett, 2015

Luke Hunter has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: PB: 978-1-4729-1219-0

ePDF: 978-1-4729-2285-4

ePub: 978-1-4729-1220-6

Maps by Lisanne Petracca/Pantherus

Skull illustrations by Sally Maclarty

Design in UK by Nicola Liddiard at Nimbus Design

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

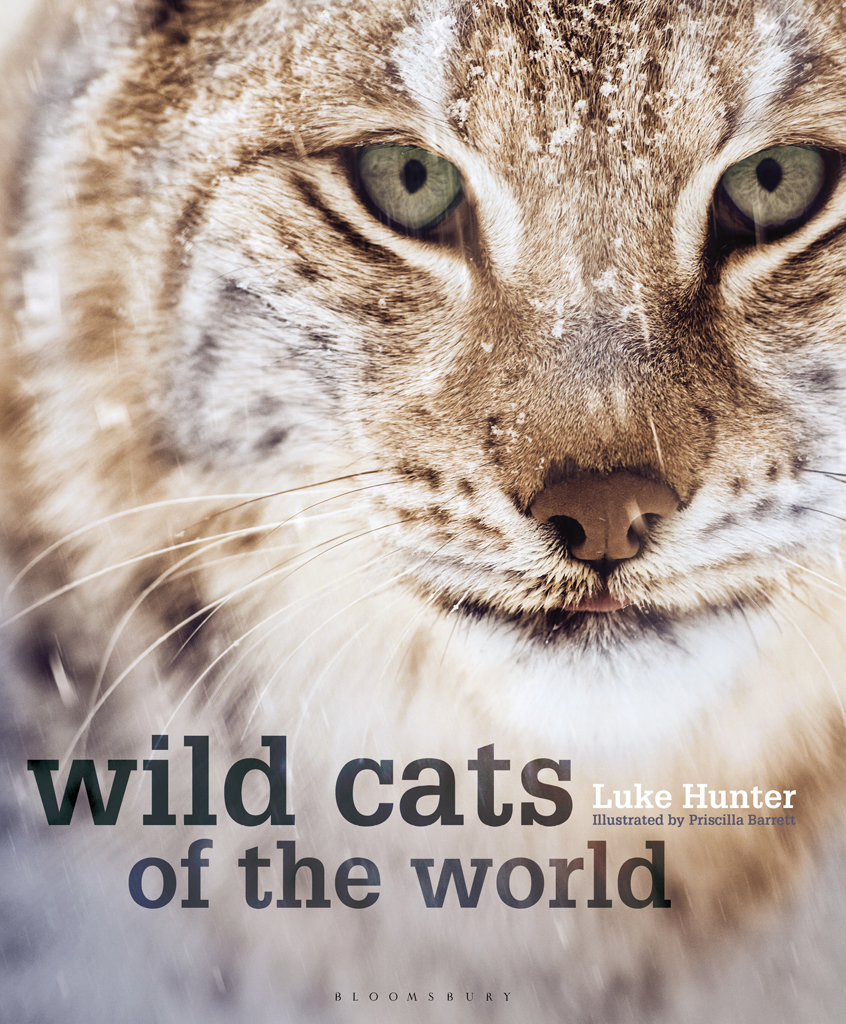

The cat family

With a global population that may exceed a billion, there are perhaps 300,000 housecats for every Tiger left on earth. The most generous population estimates for all wild cat species combined might reach one per cent of housecat numbers; 10 million wild cats, most of them small-bodied, wide-ranging generalists such as Bobcats and Leopard Cats.

The domestic cat is one of the most successful mammals on earth and its most successful carnivore. Resident cat populations occur on every major continent except Antarctica and on most of the worlds offshore islands. Cats can survive in virtually any habitat from the Sahara Desert to sub-Antarctic islands, whether they are cared for by people or not. At least half a billion cats are kept as pets around the world, and there are many hundreds of millions more that live as strays loosely associated with humans or completely feral with no reliance on people at all.

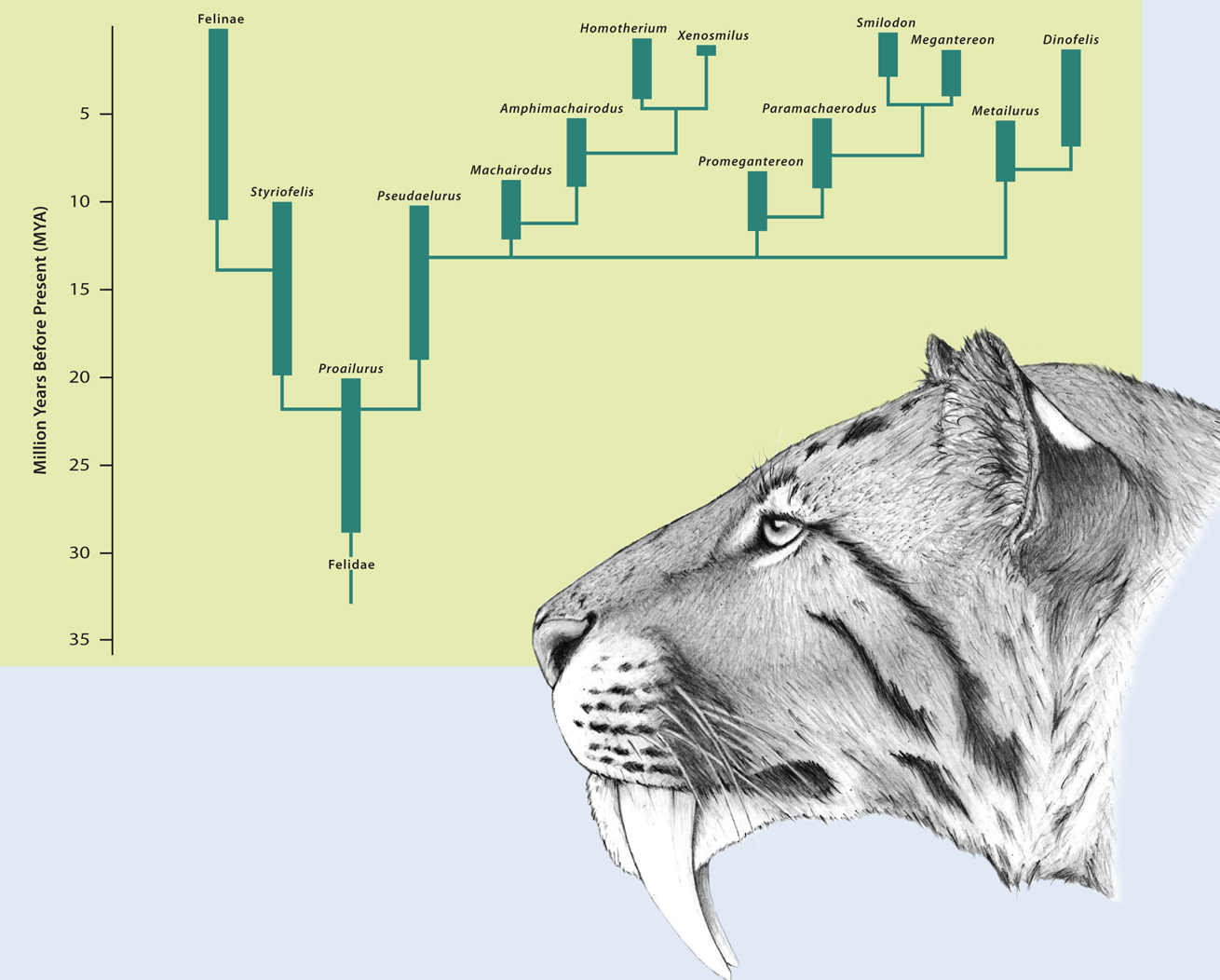

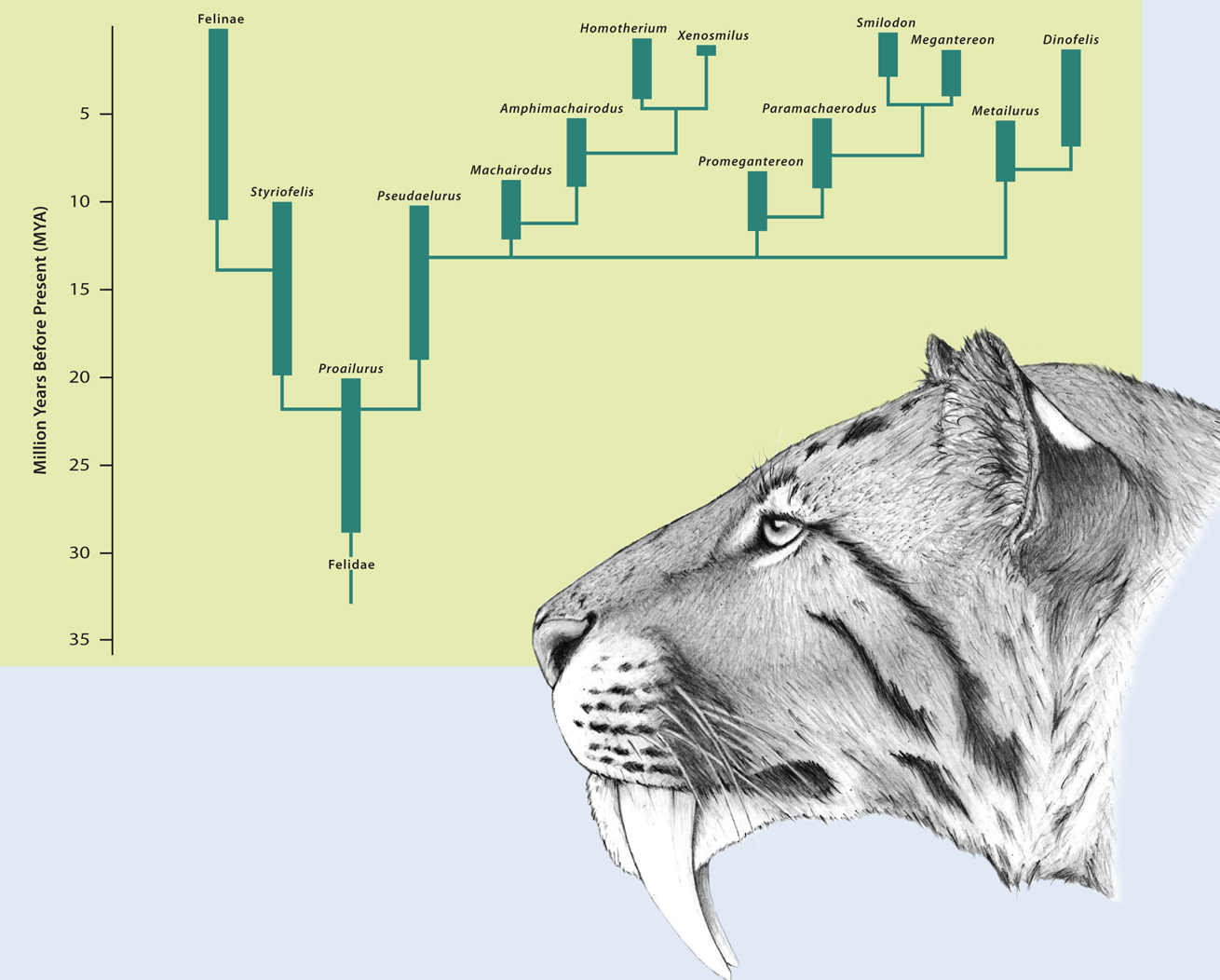

The cats success embodies the evolutionary triumph of the Family Felidae. Felids have walked the earth for around 30 million years and prior to very recent anthropogenic impacts, have been extremely successful. Felid evolution began in Eurasia where the Familys first unambiguous representative sufficiently different from earlier fossil carnivores to be considered a true cat is Proailurus lemanensis. The oldest Proailurus fossils are 2530 million years old from what was then a vast subtropical forested landscape and is now Saint-Grand-le-Puy in France. Proailurus lemanensis is the likely progenitor of all cat species, living and extinct, that have ever lived. By approximately 1820 million years ago, Proailurus had diverged into two distinct genera that seeded the two main branches of cat evolution. One of these, the genus Pseudaelurus included cats which for the first time in felid evolution had reached the size of the modern Leopard. Their skulls and teeth also carried incipient sabretooth features such that Pseudaelurus is now considered ancestral to the felid subfamily Machairodontinae, the sabretooths. This spectacular experiment in felid evolution produced many dozens of species with famously elongated canine teeth and a raft of other modifications in the skull and skeleton that differentiates them from other felids. The sabretooth cats prospered in Eurasia, Africa and the Americas until very recently. The best-known genus Smilodon lived until 10,000 years ago in North and South America, and included some of the most extraordinary, largest felids to have ever evolved. Smilodon fatalis the celebrated Californian sabretooth known from over 1,200 specimens in the Rancho la Brea tarpits was as tall as the modern Tiger but was more heavily built and weighed more, while the massive South American Smilodon populator far out-weighed any living cat at close to 400 kilograms. Both species lived alongside humans.

SABERTOOTH FAMILY TREE

The Machairodontinae and Felinae are two separate branches on the felid family tree that diverged early in cat evolution. All are true cats (Family Felidae) but all living felids are more closely related to each other than to the sabertooth cats. The misnomer sabertoothed tiger (typically used for Smilodon, pictured) is particularly erroneous; the Tiger is more closely related to the housecat than it is to any sabertooth. (Chart redrawn from Anton, M. 2013 Sabertooth Indiana University Press.)

Conversions

Throughout this book measurements, weights and areas have been provided using the metric system, however, those more used to the Imperial system may find the table useful.

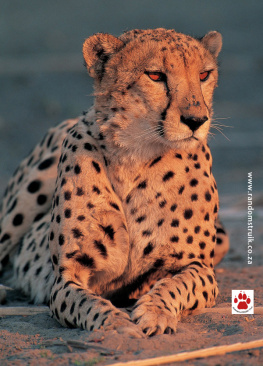

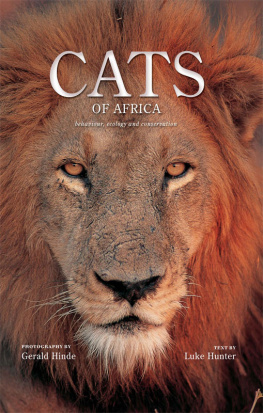

In parallel to the great proliferation of sabretooths, the second major branch of felid evolution arising from Proailurus took shape as the subfamily Felinae, the conical-toothed cats. The Felinae began with Styriofelis, a genus of relatively small species around the size of modern Wildcats to Lynxes. Just as Pseudaelurus was the progenitor of all sabretooths, Styriofelis led to all cat species living today (and many conical-toothed species which are now extinct). They evolved alongside the sabretooths, often with many members of both subfamilies occupying the same environment and presumably with the same complex interrelationships we see among modern cat species today. Nine million years ago, the landscape that today surrounds modern Madrid had at least four species of now-extinct cats representing both subfamilies. Two species of Felinae, one Wildcat-sized (Styriofelis vallesiensis) and one Serval-sized (Pristifelis attica) must have occasionally fallen prey to two sabertooth species which were the size of a small Leopard (Promegantereon ogygia) and a Lion (Machairodus aphanistus). Fast forward to the early Pleistocene of East Africa and the Felinae branch had proliferated dramatically out of the shadows of their sabretoothed cousins. Around a million years ago, the Cheetah, Leopard and Lion shared the African landscape with at least three species of large sabretooth cats. Sadly, we will never know how six large cats from the two great felid subfamilies interacted but their relationships must have been intriguing.