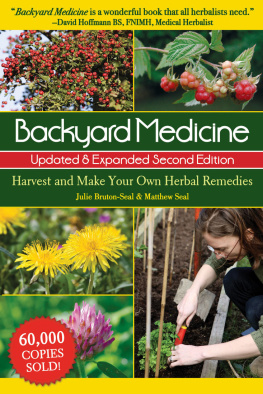

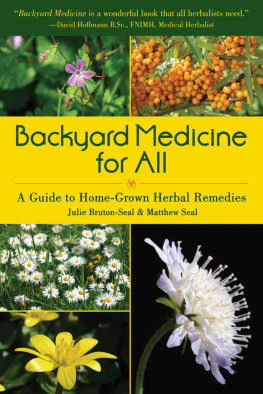

Julie Bruton-Seals long experience as a practising herbalist combined with husband Matthews publishing know-how has produced a great new herbal for the 21st century. This is the book that I take most recipes from. While there have been many excellent herbals over the years and centuries, this is the most useful to me practically. Hedgerow Medicine has become a popular book, which is unsurprising with its excellent photos and easy to use format.

At last! A herbal with photographs. I have longed for a book like this for years. It will rapidly become a classic.

This is a book about common British hedgerow plants and their medicinal uses. We began with a list of 100 species, which we thought was a severe selection already, but our publisher wisely persuaded us to concentrate on our top 50 choices in greater depth. These are all wild plants (many also occur as weeds) that are abundant, easy to identify, cost nothing to pick and in most cases will survive your harvesting. Each has well-known, sometimes forgotten or even novel medicinal values what the old herbals called the virtues of the plant.

Most of the species you find in our pages will be ones youd expect, such as nettle, elder, hawthorn, dandelion, mugwort, mullein, bramble, rose and burdock; these grow almost everywhere but are actually powerful, proven and significant herbs to which we gladly dedicate most space. Commonness is not to be despised: it means a plant has the survival adaptations needed to accompany and even thrive alongside our changing civilisation. As you will never keep clover or couch grass out of your lawn or red poppy out of your fields forever, we say: take advantage of their medicinal and survival strengths, and use them for your own benefit.

Sometimes we include less likely plants, like the majestic teasel, which we make into a flower essence for joint pain, or lycium, source of the fashionable imported goji berries but actually a British hedgerow species for over 250 years. A few plants seemed to choose us, as when self-heal invaded our garden while we were planning the book, and we looked again at its uses; rosebay and sweet cicely also eased their way in. It was difficult to make a selection, which is bound to be subjective, but all the plants we have included are ones that Julie uses in her herbal practice and has found medicinally effective.

We list the plants alphabetically by familiar common name. Each plant is given only a short description, as it is generally unmistakable, or we describe similar family members that are used interchangeably. In some instances, such as comfrey, when it is important to make an exact and positive identification, we provide precise details. We go on to outline the habitat, distribution, related species and parts used of each plant.

The text blends the history, folklore, botany, economic and other uses of the plants together with their modern herbal applications. Each entry concludes with easy-to-follow recipes and bullet points of main medicinal benefits. We tie the ailments and benefits together by including both in a comprehensive index.

In case it is gripping you to know how we divided the work, Julie the herbalist usually initiated the writing and Matthew the editor completed it, but often we operated the reverse way. The words sometimes came first and sometimes the images.

Julie was our photographer, using a Nikon D80 digital camera. Every image is original and shot for this book; in just a few cases an illustration is reproduced by Julie from an old herbal. Matthew was chauffeur and plant spotter, and fulfilled a lifetime ambition by being key grip on our photo shoots.

We worked together on choice of pictures and design template, but the books appearance is essentially the result of another collaboration, that between Julie and InDesign software. Our goal was to make visually stimulating spreads, with a few sumptuous full-page pictures, in our publishers phrase, and a friendly but informed text. Asked for at least ten larger images, we supplied well over twenty. We hope the armchair reader will be inspired into harvesting action.

We particularly thank practising fellow herbalists Christine Herbert and Paula Stone, who read most of the text and saved us from some embarrassing errors. Needless to say, the opinions expressed here are our own, and we take responsibility for them.

We have acknowledged sources in the notes to the text, and thank copyright holders for permission to include extracts from their work. If we have overlooked or been unable to locate copyright owners we will gladly add details in a later edition.

We are especially grateful to the books godparents, Merlin and Karen Unwin, for their forbearance and intrepidity: not many publishers would have entrusted unknown authors with the design, organisation, editing and copy-editing of their own book.

We are grateful to the John Innes Foundation Collection of Rare Botanical Books and Ken Dick, the former Librarian, for wonderful access to a splendid botanical library, with its added virtue of being situated so close to our home; we also thank the British Library and Norfolk Record Office for unfailing help.

We travelled widely over England and Wales in pursuit of our plants, and thank Karin and Peter Haile for herbal hospitality. There are too many delightful and helpful B&B owners to name individually, so well simply recommend Alastair Sawdays books and website as a guide to lovely places to stay.

The book was planned in early 2006, with photography in earnest from autumn 2006 into autumn 2007. This tight schedule meant we had a calendar year for everything. We had one shot, sometimes literally, at some plants, and fell foul of the weather in the wet spring and summer of 2007, notably for hawthorn flowers. We did get some shots, as the vignette shows, but never the stunning big landscape view we wanted. Many photos were taken from beneath the protection of an umbrella held by the intrepid, soaked key grip. We also had some close scrapes, such as finding bilberries in Surrey and wood betony in Lincolnshire when wed almost given up on them.

We shouldnt end without thanking the plants. Hedgerow medicine-harvesting, like foraging for wild food, is best done with respect for both habitat and individual plants. In the vervain entry we quote an old prayer of thanks used when picking it; we received gifts from all fifty of our plants. And we now begin to understand why Dutch herbalist Herman Boerhaave would lift his hat in respect whenever he walked by mother elder.