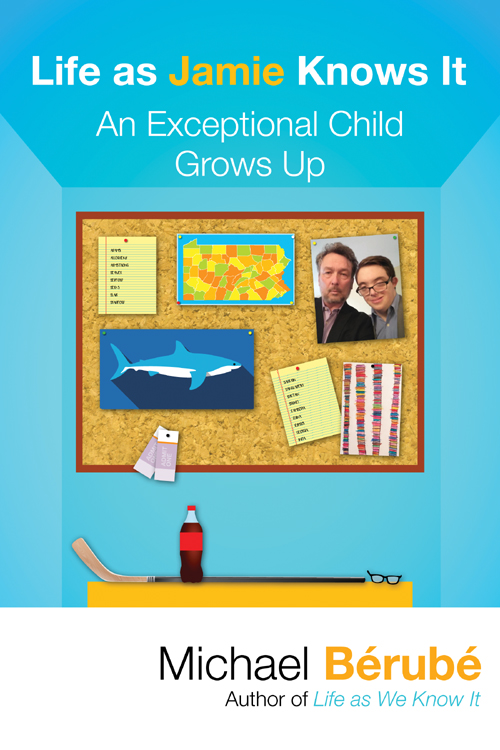

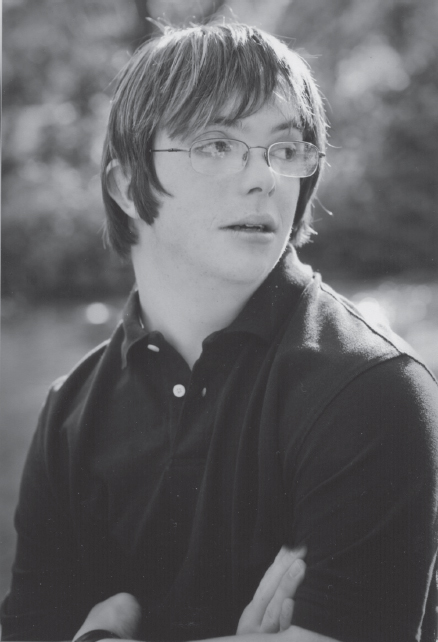

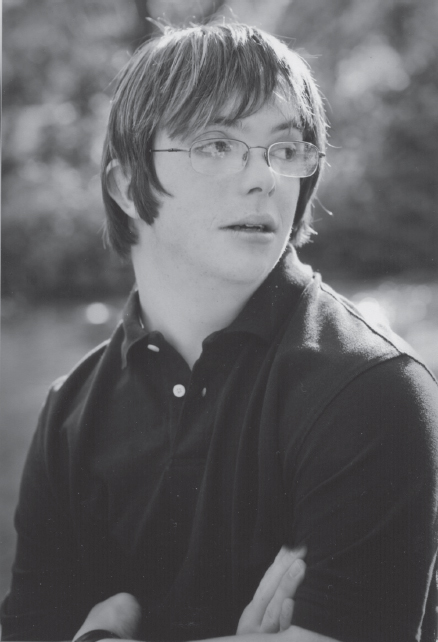

Jamie Brub, senior portrait, State College Area High School yearbook, 2011.

Photo: Helen Richardson, courtesy of the Brub family

It took a couple of villages to raise Jamie. He is lucky to have a wonderful extended family and family friends; on Janets side especially, he has spent innumerable days of delight with awesome aunts, uncles, and cousins, and my own birth family has always loved him dearly. But in the villages of Champaign, Illinois, and State College, Pennsylvania, we could not have raised Jamie without the help of the physical, occupational, and speech therapists of his youth, his medical professionals, and his dozens of teachers and paraprofessionalsnot to mention his legions of paid companions (formerly known as babysitters), all of whom he remembers fondly and vividly. To all of them, to his Special Olympics coaches and volunteers, and to his current employers and assistants and associates in the grown-up world of work, this book is dedicated.

Reintroducing Jamie Brub

My little Jamie loves lists. That was how I opened Life as We Know It twenty years ago, writing my first draft when Jamie was only three and a half years old. Well, my Jamie is no longer little. But he still loves lists; he is, I think, the most astonishing and assiduous maker of lists I have ever met. When he has to entertain himselfwhen he is waiting for breakfast or sitting through one of his parents lectures or just keeping himself occupied while he watches one of his dozens of wrestling videoshe takes out a legal pad and writes down (a) various Beatles songs along with the year of their release or (b) various opponents of the wrestler known as the Undertaker or (c) cities from one of his world atlases, cities from the Middle East or Central Asia or Indonesia or South America or Wisconsin, or (d) all sixty-seven Pennsylvania counties in alphabetical order, from Adams to York. He makes all his lists from memory, with the exception of the cities lists, which he copies out of the atlas.

We have hundreds of these legal pads in our house, and we are always buying more.

I am not sure exactly when little Jamie stopped being little. In his tween years he was still a waifshort, skinny, and easy to carry if carrying was needed. I have a video of him from late 2002, when he was eleven, and his voice is impossibly high and squeaky. Then again, that was true also of preadolescent Nick, and I wondered, as I went through our old family videos to convert them to DVDs, Was there a time when my children huffed helium? Down syndrome is associated with shortness of stature, and my wife, Janet, once predicted that Jamie would grow no taller than 5 feet 2 inches. I said 5 feet 6 inches. I won the Jamie height-prediction pool: Jamie is now 5 feet 7 inches, and somewhere in his teen years he developed wide, powerful shoulders and a strong upper body. He is a Special Olympics swimmer and loves work tasks that involve physical exertion. Buying him dress shirts is a challenge: he has an eighteen-inch neck, almost like a football linemans, and a short torso. But we think that, all in all, he is a reasonably attractive young man.

In French, he would be (and I sometimes call him) un gentil et sympathique jeune homme. (Aussi, entre nous, il est adorable.) He is bright, gregarious, even ebullient in social gatherings, and his lists are the product of his amazing cataloguing memory and his insatiable intellectual curiosity about the worldits people, its creatures, its nations, its languages, and (perhaps most of all) its culinary traditions. If it were possible for Jamie to travel everywhere on the inhabited globe, he would do it, and he would try to ingratiate himself with his hosts, just as he does when he greets the owner of our local Indian restaurant by bowing, hands clasped, and saying, Namaskar. (The owner, Sohan Dadra, is delighted by this.)

In the years after the publication of Life as We Know It, I was warnedrepeatedly and emphaticallythat its all very well and good to write about a child with an intellectual disability when your child is young and cute. Children with intellectual disabilities go over best, evidently, when they are young and cute, long before anybody has to worry about things like their adolescent friendships (or lack thereof) and their burgeoning sexuality and their thoughts about mortality and their prospects for employment. Adults with intellectual disabilities are another thing entirely: any number of peoplethough I have not made a list of their nameswho coo solicitously over a toddler with Down syndrome might find themselves recoiling, either from awkwardness or from outright revulsion, from the adult with Down syndrome who sits down next to them on the bus.

So let me establish this much at the very outset: my little Jamie is no longer little. But he has remained cute for twenty yearsexcept that his cuteness, as he has grown, has taken forms no one could have imagined when he was little. Sometimes it is a matter of realizing that our Jamie can be witty and observant, even incisively so; sometimes it is a matter of understanding how dramatically his own self-understanding has deepened as he has grown.

I think of the fresh spring day in 2002 when Jamie informed me that we could not walk to school (he was in fourth grade) because the ground was strewn with berries and we would have polka-dot feet. Or I think of the moment in early 2005 when we emerged from the local gym, having done our racquetball-and-swimming routine for the weekend, and Jamie, seeing me put his gym card in my wallet, declared, Michael! Thats my card! I can have a wallet. Im a teenager. Im allowed. (Ever since then he has called me Michael, though we occasionally call each other sir. And ever since then, he has had a wallet. I took him at once to Target, where we bought a wallet and placed his gym card and his school ID in it. The next morning he walked to the bus stop with his right hand placed firmly on his back pocket, with his mind on his wallet and his wallet on his mind.) Or I think of our trip to Boulder, Colorado, in 2008, where I was to speak at the Coleman Institute for Cognitive Disabilities, and I showed Jamie the design of the Denver International Airport, with its famous peaked canopy roof, white fabric stretched over the skeleton of the main terminal. Some people say it looks like the snowy mountains of Colorado, I told Jamie, some people say it looks like tents or Native American tepees. And some people say it looks like the meringue on a lemon meringue pie. You know, the pie with the white fluffy stuff on top?

Mm hm. Jamie nodded, adding something unintelligible.

Im sorry, sweetie, what did you say?

He repeated the unintelligible word unintelligibly. This happens now and again; his speech tends to be unclear, and he sometimes isnt sure he has the right word, as when he told me to shave with a rooster when he meant shave with a razor (he was four) or when he complained, in the course of a long walk, that we would be like the Ramones (he was sixteen, and Nick and I never found out just what he meant). To make matters worse, he speaks too quickly, most likely because he has a father who speaks too quickly. Fortunately, he has seemingly endless reserves of patience when people ask him to repeat himself, and I know of only a handful of instances in which he became frustrated with his auditorsas when he finally explained to his family, after repeatedly asking for soosee, that it comes from Japan.

![Jamie Knight [Jamie Knight] - Revealing His Virgin](/uploads/posts/book/141323/thumbs/jamie-knight-jamie-knight-revealing-his-virgin.jpg)