CONTENTS

PREFACE

Seventeen years ago I moved to London from Japan and after three years I began my cookery school, Hashi Cooking. I teach students ranging from complete beginners to professional chefs how to make authentic Japanese recipes, with a little fusion inspired by my travels around the world.

I had never dreamt that my teaching could reach the level that it is now, but it seemed to develop naturally. I enjoy interacting and connecting with people. Its always been in me. Teaching my culinary heritage and Japanese cooking skills is an extremely important part of my life and I feel extremely blessed to do what I am most passionate about.

Growing up, I was fortunate enough to have had a mother who cooked fresh food for each and every meal, every day. I remember, as a child, I would wake up and go downstairs to the familiar sound of grating in the kitchen. This was my mother, shaving a solid piece of dried and smoked bonito fish to make the flakes for dashi stock. Each day she would shave the fish to obtain the freshest bonito flakes that were then made into dashi stock for miso soup, which was served at breakfast. These days most home cooks use instant dashi stock powder to make this soup, but if you were brought up with the fresh, real flavour it is hard to come to terms with these fast, modern alternatives.

My family continue to live in Kyoto where I grew up, a city in which we always had an abundance of seasonal mountain vegetables. Like most Japanese chefs, I learnt to cook with the seasons to achieve the best flavours. I return to Japan once a year, often in the spring or autumn as this is when my favourite ingredients are available. Early in the spring, I look out for the woody and nutty flavour of freshly picked bamboo shoots, while in autumn I am drawn towards matsutake mushrooms, also known as the Japanese truffle. Simmered lightly in dashi stock and served with the citrus fruit yuzu to cut through their earthy flavour, these mushrooms taste divine.

It is these moments of sheer joy that have developed my dedication to real Japanese flavours, and to introduce them to others through my teaching. At its core, my teaching style looks to challenge the myth that Japanese cooking is complex and mysterious. I want to break down these barriers by providing easy-to-follow recipes and cooking methods that can be painlessly adapted to the Western kitchen, as well as explaining the versatility and nutritional properties of unfamiliar ingredients.

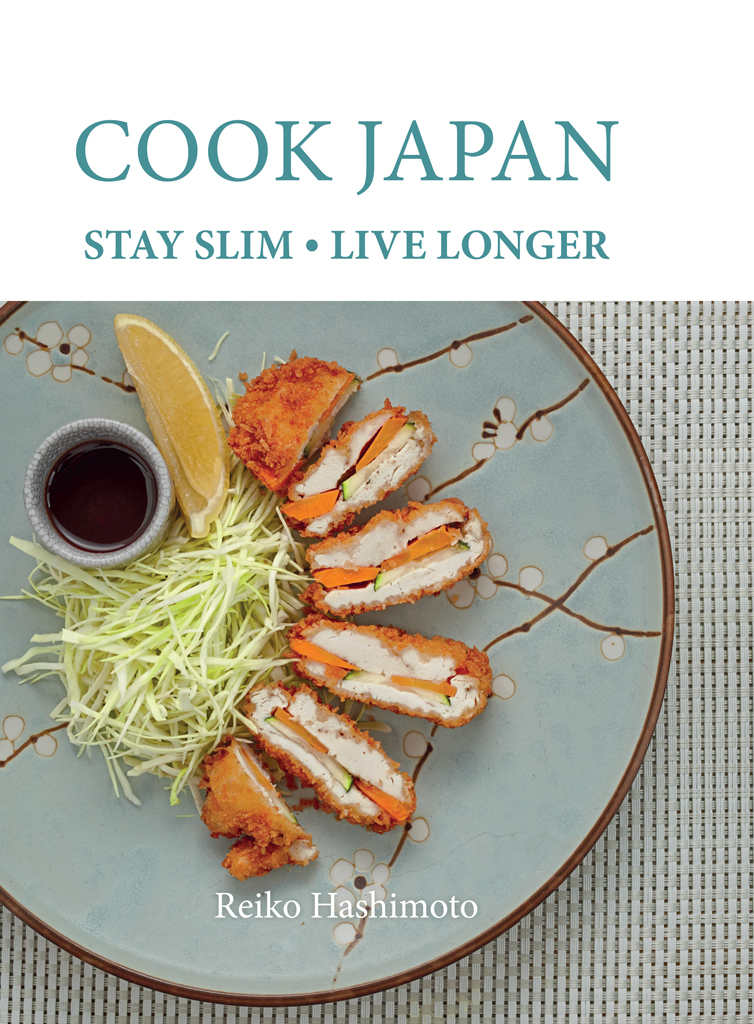

The Japanese Diet

As a health-conscious chef, I have long been aware of the specific health benefits of the Japanese diet. Japan boasts one of the highest life expectancies in the world, and only 3.6 per cent of the Japanese population have a body mass index over 30, which is the international standard for obesity, compared to 32 per cent of Americans. The reasons for this are undoubtedly the diet, with many Japanese people subscribing to the notion eat with your eyes a nod to the importance of colours, crockery and food presentation.

Typically, Japanese meals consist of an array of textures and flavours, which are eaten slowly and, in comparison to the western diet, contain fewer fats or processed ingredients, and far less dairy and meat. Versatile ingredients such as miso and two of my personal favourites seaweed and tofu contain an array of vitamins and minerals that promote excellent health, and most importantly lead to mouthwateringly good food. Tofu is revered in Japan, and Kyoto in particular is famous for the delicacy of its tofu, but in the west this ingredient is often neglected or considered vegetarian-only. Tofu is something I try to eat every day during my visits to Kyoto, as it is beautifully clean and rich and you can find a huge variety of types from different regions. I suppose we see tofu as the French see cheese. Although it may be unlikely to find tofu of quite the same quality in the UK, the recipes in this book, I hope, will teach an appreciation of this unique and delicious ingredient.

Offering authentic and clearly explained recipes, this book is your gateway to the cuisine that gives Japan one of the lowest obesity rates and longest life expectancies in the world. It also offers you an insight into the food culture of Japan, which has remained so close to my heart.

INTRODUCTION

COOK JAPAN

Food really is central to Japanese culture. From mothers creating bento boxes each day for their children to take to school to friends gathering around a nabemono (hotpot) for a shared meal or visiting sushi bars to have your food prepared in front of your eyes food is everywhere.

In Japan we have different kinds of restaurants for different kinds of foods and experiences and visit them accordingly: an okonomi-yaki restaurant for an okonomi-yaki pancake, a ramen shop for ramen noodles (and each with its own speciality broth), and of course a sushi bar for sushi. Japanese diners have an extremely discerning palate, especially when it comes to rice. In fact, many people might be surprised to hear that sushi restaurants are rated based on the quality of their rice rather than their fish.

Another crucial aspect of Japanese food, especially sushi, is presentation, something which has made the dish popular worldwide. The importance of presentation is key to every meal every day in Japan, as families dine from many small and beautiful pieces of crockery, each with its own shape and texture to enhance the appearance of the food and the pleasure of dining. If you ever wondered why Japanese knives are renowned for being so sharp, just consider the visual effect of a perfectly cut piece of fish or vegetable upon a plate. This is why it is crucial to invest in a good knife when beginning your journey into Japanese food. When presenting a meal, consider how you slice your vegetables, tofu or meat and the colour combinations. Bear in mind that when we eat with chopsticks, we tend to slow down so this is another reason why we should try to ensure good presentation. Youll find yourself enjoying looking at your meal for so much longer.

STAY SLIM

Each time I return to Japan I notice that, in general, people are very slim. In recent years the obesity rate in Japan has risen slightly however, coinciding with the increasing popularity of western recipes, food products and eating habits in Japan. So what is it about the traditional Japanese diet that keeps the Japanese so slim?

Typically, Japanese meals consist of an array of dishes, textures and flavours which are eaten slowly with chopsticks, served in small portions and savoured. The Japanese table is considered a work of art, with presentation an extremely important part of the dining experience. This, along with the well-known saying eat only until youre 80 per cent full and the specific set of ingredients we use, have led to Japan having the lowest obesity rate in the developing world.

In comparison to many western diets, the Japanese diet is low in fat animal fats and dairy in particular with milk often supplemented with a soy alternative and meat replaced by soya products such as tofu. Tofu is an incredibly versatile ingredient that is so often misused, however it is incredibly high in protein, easy to transform into a delicious dish and contains less fat and fewer calories than the same quantity of meat. The Japanese diet takes the rest of its protein mainly from seeds and fish, the latter of which also contains good fats and minerals.