VIRUSES AS COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS PRIMERS IN COMPLEX SYSTEMS EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD John H. Miller, Editor-in-Chief, Carnegie Mellon University and Santa Fe Institute Murray Gell-Mann, Santa Fe Institute David Krakauer, Santa Fe Institute Simon Levin, Princeton University Mark Newman, University of Michigan Dan Rockmore, Dartmouth College Geoffrey West, Santa Fe Institute Jon Wilkins, Santa Fe Institute VOLUMES PUBLISHED IN THE SERIESViruses as Complex Adaptive Systems, by Ricard Sol and Santiago F. Elena (2019) Natural Complexity: A Modeling Handbook, by Paul Charbonneau (2017) Spin Glasses and Complexity, by Daniel L. Stein and Charles M. Newman (2013) Diversity and Complexity, by Scott E. Page (2011) Phase Transitions, by Ricard V.

VIRUSES AS COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS PRIMERS IN COMPLEX SYSTEMS EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD John H. Miller, Editor-in-Chief, Carnegie Mellon University and Santa Fe Institute Murray Gell-Mann, Santa Fe Institute David Krakauer, Santa Fe Institute Simon Levin, Princeton University Mark Newman, University of Michigan Dan Rockmore, Dartmouth College Geoffrey West, Santa Fe Institute Jon Wilkins, Santa Fe Institute VOLUMES PUBLISHED IN THE SERIESViruses as Complex Adaptive Systems, by Ricard Sol and Santiago F. Elena (2019) Natural Complexity: A Modeling Handbook, by Paul Charbonneau (2017) Spin Glasses and Complexity, by Daniel L. Stein and Charles M. Newman (2013) Diversity and Complexity, by Scott E. Page (2011) Phase Transitions, by Ricard V.

Sol (2011) Ant Encounters: Interaction Networks and Colony Behavior, by Deborah M. Gordon (2010) VIRUSES AS COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS Ricard Sol and Santiago F. Elena P R I N C E T O N U N I V E R S I T Y P R E S S Princeton & Oxford Copyright 2019 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-691-15884-6 LCCN 2018954901 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Editorial: Alison Kalett and Lauren Bucca Production Editorial: Brigitte Pelner Jacket/Cover Credit: Cover art courtesy of Shutterstock Production: Jacqueline Poirier Publicity: Alyssa Sanford This book has been composed in Adobe Garamond and Helvetica Neue Printed on acid-free paper Typeset by Nova Techset Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 C O N T E N T S vi Contents Contents vii P R E F A C E Few examples of the way complexity unfolds in nature (and beyond it) are as fascinating as viruses. Viruses are hypothesized by some to predate the origins of life and its micro- and macroevolutionary play. They strongly influence energy flows in complex ecosystems. They maintain all kinds of relationships with their hosts, from mutualism to pure parasitism.

They are responsible for some of the most deadly pandemics and yet have been coevolving with us throughout all our common history. They have played a major role in our understanding and manip ulation of life and have also attracted the interest of biologists, physicists, and computer scientists alike. Many key questions emerge when thinking of their nature and relevance: What exactly are they? Are they living entities? How did they originate? How similar are computer viruses to their living counterparts? How complex can they become? What is their role in shaping the evolution of complex organisms? What role have they played in the development of society? Can they be compared with software programs, to be run inside their hosts, who provide the appropriate hardware? Why are there so many new emergent viruses and how do they emerge? These questions will be addressed in this book. x Preface Viruses are complex systems, spanning orders of magnitude in size, and an enormous variety of life cycles and habitats. But the study of their behavior and structure, particularly from interdisciplinary frameworks, has also revealed a number of universal patterns of organization. RNA-based viruses display high mutation rates, as predicted by theoretical developments from the 1970s.

They live at the edge of disorder, where high instability but also adaptability occur. This edge is related to a phase transition phenomenon, and its presence is tied to the genetic nature of populations, often described as quasispecies. Other viruses, such as the mimiviruses, are so big that they are actually larger than some of the smallest cells we know. Their life cycle reveals surprising properties, placing them in a new position as a parasitic life form. We will discuss the potential boundaries of the viral morphospace and their importance, as well as theoretical models of viral population dynamics and self-assembly. Models and theoretical approximations have played a key role in this area, in particular the concept of fitness landscapes given their importance in defining the dynamics of their genetically complex populations.

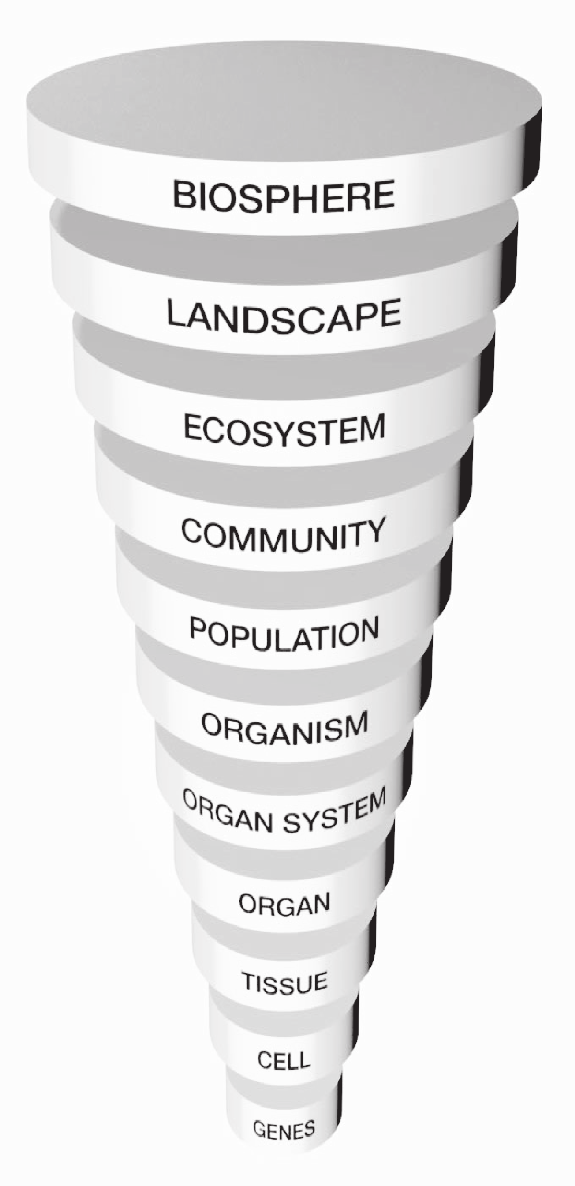

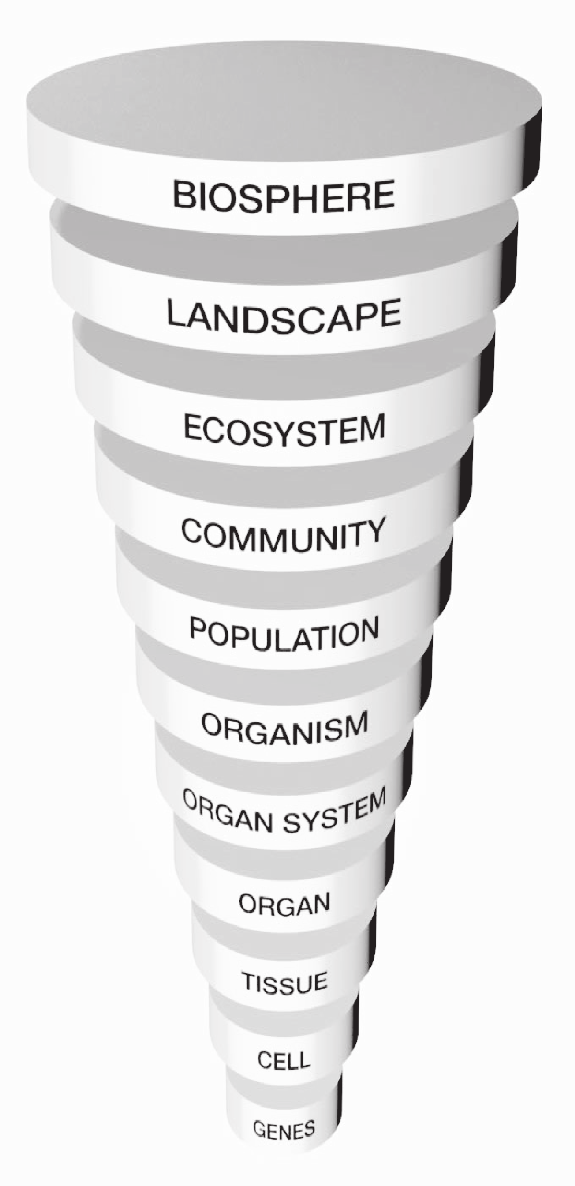

Viruses have shaped the evolution of cells, organisms, ecosys tems and even the biosphere. Such influence spans all scales of biological organization, from genomes to the planet ). Their dynamics involve nonlinear phenomena, tipping points and self-organization processes that have many commonalities with other biological and nonbiological systems. Such similarities might hide universal properties that pervade complexity and in this respect viruses offer a unique window into the origins of complex systems. In this context, we will also pay attention to other systems, such as computer viruses, that share unexpected similarities. Although many excellent books exist concerning the popula tion biology and ecology of viruses or the role they have played within the context of epidemics, there is no major contribution in  Preface xi Marine viruses drive the large-scale turnover Ecological disturbance a of bacterial cells and allows viruses to spill over indirectly (but deeply) from reservoirs to new hosts influence climate and geochemical cycles Epidemics caused by viral Bacteria-phage and other agents have a major impact virus-host interaction networks drive biodiversity changes at the community Viruses are required to level complete the life cycles of several species of insects, such as parasitoids Endogenous retroviruses are required for the RNA viruses infecting maturation and vertebrates have triggered development of vertebrate the evolution of a complex placenta and hypervariable immune cell response.

Preface xi Marine viruses drive the large-scale turnover Ecological disturbance a of bacterial cells and allows viruses to spill over indirectly (but deeply) from reservoirs to new hosts influence climate and geochemical cycles Epidemics caused by viral Bacteria-phage and other agents have a major impact virus-host interaction networks drive biodiversity changes at the community Viruses are required to level complete the life cycles of several species of insects, such as parasitoids Endogenous retroviruses are required for the RNA viruses infecting maturation and vertebrates have triggered development of vertebrate the evolution of a complex placenta and hypervariable immune cell response.

The evolution of cells has been deeply influenced by their interaction with intracellular Molecular innovations, parasites including the origin of DNA from ancestral RNA molecules Origin of first molecular replicator parasites Figure 1. All scales of life are affected by and affect the diversity and evolution of viruses in the biosphere. In this diagram, some key processes and phenomena influenced or caused by viruses are indicated (central picture after Odum and Barrett (2005)). the existing literature that provides the unifying picture presented here. The book has been written to be of interest to researchers and graduate students in virology, evolution, mathematical bio logy, and physics of complex systems. But we also hope it will be appealing to advanced undergraduate students interested in xii Preface broad questions about viruses: where they come from, where they may go, and whether they are alive or not.

Because of its multidisciplinary nature, some parts of the book require familiarity with intermediate-level algebra and calculus. Similarly, the book requires a basic understanding of molecular biology and the processes of information flow within the cells from DNA to proteins. We have made an effort to write every chapter in the most intelligible way, and more biology-oriented readers may skip over the mathematical details but still catch a good sense of what models represent and prove. We would like to thank our many colleagues within virology and complex systems who have been helpful in shaping the ideas presented here, from both the experimental and theoretical sides, including some researchers, visitors, and good friends from the Santa Fe Institute. In particular, we would like to thank Lin Chao, Paqui de la Iglesia, Esteban Domingo, Stephanie Forrest, Fernando Garca-Arenal, Murray Gell-Mann, John J. Holland, Stuart Kauffman, Eugene Koonin, Chris Langton, Susanna Manrubia, Melanie Moses, Andrs Moya, Tom Ray, Rafael Sanjun, Josep Sardanys, Joan Saldanya, Peter Schuster, Paul Turner, Sergi Valverde, Ers Szathmry, Mark Zwart, plus a quite long list of PhD students, postdocs, technicians, and collaborators both in Barcelona and in Valncia The late physicist John Wheeler said about science: We live on an island surrounded by a sea of ignorance.

Next page

VIRUSES AS COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS PRIMERS IN COMPLEX SYSTEMS EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD John H. Miller, Editor-in-Chief, Carnegie Mellon University and Santa Fe Institute Murray Gell-Mann, Santa Fe Institute David Krakauer, Santa Fe Institute Simon Levin, Princeton University Mark Newman, University of Michigan Dan Rockmore, Dartmouth College Geoffrey West, Santa Fe Institute Jon Wilkins, Santa Fe Institute VOLUMES PUBLISHED IN THE SERIESViruses as Complex Adaptive Systems, by Ricard Sol and Santiago F. Elena (2019) Natural Complexity: A Modeling Handbook, by Paul Charbonneau (2017) Spin Glasses and Complexity, by Daniel L. Stein and Charles M. Newman (2013) Diversity and Complexity, by Scott E. Page (2011) Phase Transitions, by Ricard V.

VIRUSES AS COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS PRIMERS IN COMPLEX SYSTEMS EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD John H. Miller, Editor-in-Chief, Carnegie Mellon University and Santa Fe Institute Murray Gell-Mann, Santa Fe Institute David Krakauer, Santa Fe Institute Simon Levin, Princeton University Mark Newman, University of Michigan Dan Rockmore, Dartmouth College Geoffrey West, Santa Fe Institute Jon Wilkins, Santa Fe Institute VOLUMES PUBLISHED IN THE SERIESViruses as Complex Adaptive Systems, by Ricard Sol and Santiago F. Elena (2019) Natural Complexity: A Modeling Handbook, by Paul Charbonneau (2017) Spin Glasses and Complexity, by Daniel L. Stein and Charles M. Newman (2013) Diversity and Complexity, by Scott E. Page (2011) Phase Transitions, by Ricard V. Preface xi Marine viruses drive the large-scale turnover Ecological disturbance a of bacterial cells and allows viruses to spill over indirectly (but deeply) from reservoirs to new hosts influence climate and geochemical cycles Epidemics caused by viral Bacteria-phage and other agents have a major impact virus-host interaction networks drive biodiversity changes at the community Viruses are required to level complete the life cycles of several species of insects, such as parasitoids Endogenous retroviruses are required for the RNA viruses infecting maturation and vertebrates have triggered development of vertebrate the evolution of a complex placenta and hypervariable immune cell response.

Preface xi Marine viruses drive the large-scale turnover Ecological disturbance a of bacterial cells and allows viruses to spill over indirectly (but deeply) from reservoirs to new hosts influence climate and geochemical cycles Epidemics caused by viral Bacteria-phage and other agents have a major impact virus-host interaction networks drive biodiversity changes at the community Viruses are required to level complete the life cycles of several species of insects, such as parasitoids Endogenous retroviruses are required for the RNA viruses infecting maturation and vertebrates have triggered development of vertebrate the evolution of a complex placenta and hypervariable immune cell response.