Tokyo. Home to 10% of Japans population, Tokyo would take a lifetime to fully explore. Rather than any coherent center there is a mosaic of colorful neighborhoodsShibuya, Asakusa, Ginza, Tsukiji, Shinjuku, and dozens moreeach with its own texture.

Side Trips from Tokyo. A quick train ride to Nikko or Kamakura will provide all your shrine and temple viewings. Hakone offers spectacular views of Mt. Fuji and numerous lakes. In Kamakura, the 37-foot Daibutsuthe Great Buddhahas sat for seven centuries, gazing inward.

Nagoya, Ise-Shima, and the Kii Peninsula. Ise Jingu (Grand Shrines of Ise)the most important site in Japans national religionis found in Ise-Shima National Park. To the south, the Kii Peninsula has magnificent coastal scenery and fishing villages. Inland, the mountain monastery of Koya-san looms mythically with 120 temples.

The Japan Alps and the North Chubu Coast. Soaring mountains, slices of old Japan, famed lacquerware and superb hiking, skiing, and onsen soaking are found here. In Kanazawa is Kenroku Garden, one of the three finest in the country.

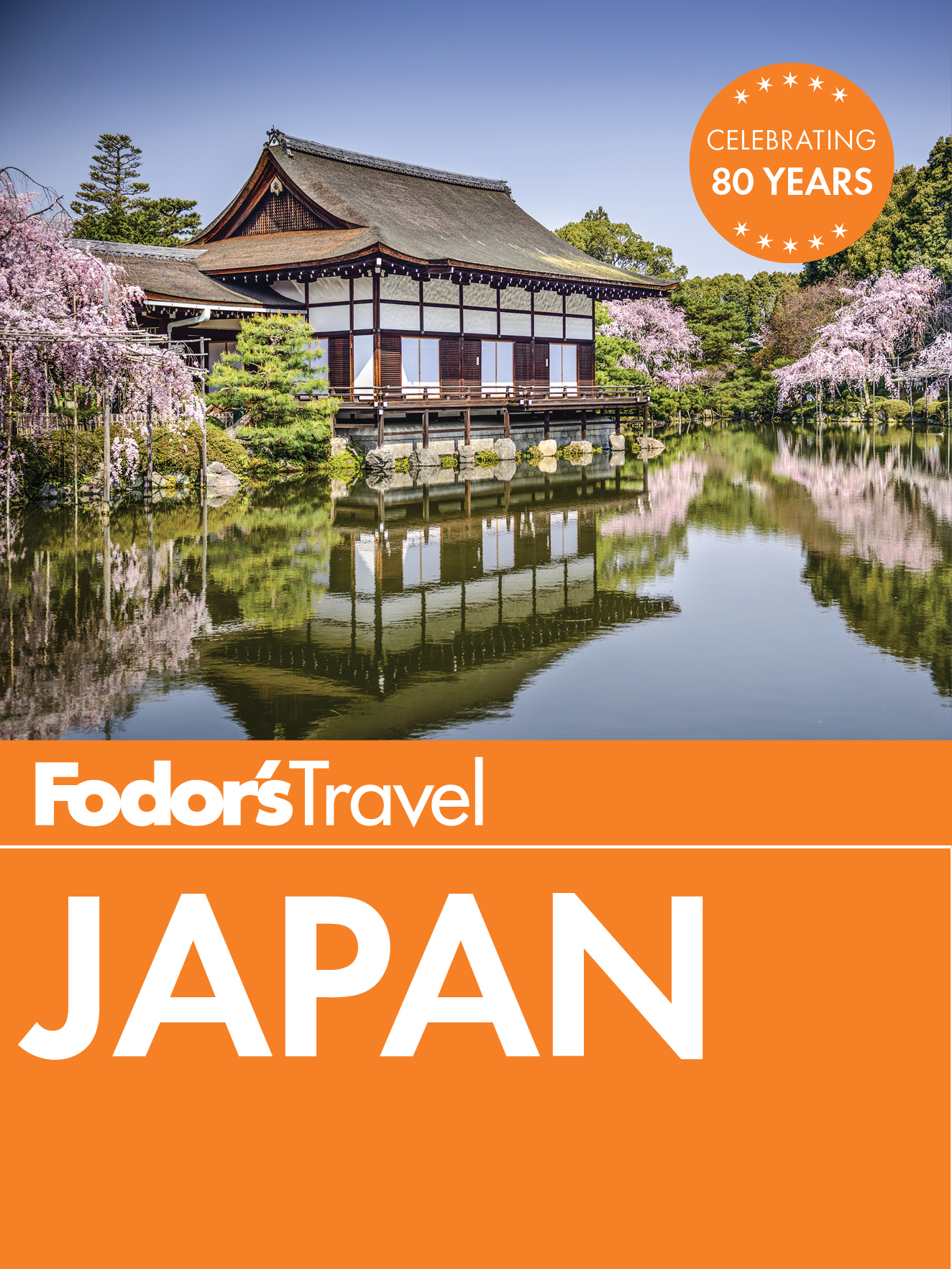

Kyoto. Japans ancient capital, Kyoto represents 12 centuries worth of history and tradition in its beautiful gardens, castles, museums, and nearly 2,000 temples and shrinesKinkaku-ji and Kiyomizu-dera top most itineraries. Here youll also see geisha and sample kaiseki ryori, an elegant meal.

The Kansai Region. Nara may not match Kyotos abundance of sacred sites, but its expansive park and Great Buddha at Todaiji Temple are among Japans finest. Osaka offers a mix of bright lights, as in the Dotombori entertainment area, and tradition, such as at Osaka-jo castle. Just minutes by train from Osaka is Kobe, where European and Japanese influences have long mingled.

Western Honshu. Mountains divide this region into an urban south and a rural north. Hiroshima is the modern stronghold, where the sobering remnants of the charred A-Bomb Dome testify to darker times. Offshore at Miyajima, the famous torii shrine gate appears to float on the water. In Okayama, Bizen masters craft the famous local pottery.

Shikoku. Thanks to its isolation, this southern island has held on to its traditions and staved off the industry that blights parts of Japan. Theres great hiking, dramatic scenery, some of the countrys freshest seafood, and the cant-miss traditional dancing at the Awa Odori festival in Tokushima.

Kyushu. Rich in history and heavily reliant on the agriculture industry, lush Kyushu is the southernmost of Japans four main islands. At Aso National Park you can look into the steaming caldera of Mt. Naka-dake, an active volcano. With its rolling hills and streetcars, Nagasaki is often called the San Francisco of Japan, a testament to the citys resurrection from the second atomic bomb.

Okinawa. Okinawa is known as the Hawaii of Japan. Relaxation and water sports are the main attractions of this archipelago, located some 700 km (435 miles) south of Kyushu. A paradise for snorkelers and scuba divers, the islands teem with reefs, canyons, and shelves of coral.

Tohoku. Mt. Zao draws skiers, while tourists clamor for a look at the juhyo, snow-covered fir trees that resemble fairy-tale monsters. Sendai is a good base for trips to Mt. Zao and Matsushima, a bay studded with more than 250 pine tree-covered islands. Make time for the traditional town of Kakunodate and Japans deepest lake, Tazawa-ko.

Hokkaido. Japans northernmost island is also its last frontier. Glorious landscapes, hiking, and skiing adventures await. In February, the Sapporo Snow Festival dazzles with huge ice sculptures. To the south are the famous hot springs of Noboribetsu Onsen and Jigokudani (Valley of Hell), a volcanic crater that belches boiling water and sulfurous vapors.

Politics

After Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi retired in 2006 following an enthusiastic spree of free-market economic reforms, Japan stumbled through seven years of political instability. Three prime ministers from the Liberal Democratic PartyShinzo Abe, Yasuo Fukuda, and Taro Asocame and went in quick succession without consolidating leadership. Fed up with LDP fecklessness, the Japanese public elected Yukio Hatoyama from the Democratic Party of Japan in 2009, turfing the LDP from power for the first time in decades. Unable to deliver on his big campaign promises, including a pledge to move the U.S. military base in Okinawa, Hatoyama resigned after less than a year in office. He passed the DPJ reigns to two short-lived successors who couldnt break through the political gridlock. Finally, elections in 2013 brought the LDPs Shinzo Abe back for another go at leading the country, and he agian won a majority in December 2014. This time, Abe promised an ambitious Abenomics economic development strategy while making no secret of his hope to amend Japans pacifist constitution to allow the nation to maintain a standing army. Public reaction to the former has been enthusiastic; to the latter, ambivalent. An increasingly assertive China has many wondering if Japan should remove the constitutional constraints on its Self Defense Forces, but memories of World War II are fresh enough in collective memory to prompt second thoughts. At the core of this national debate and political maneuvering is the issue of how Japan sees itself: a bold nation actively shaping world affairs, or a peaceful middle power focused on growing an economy that assures the good life?