Preaching chastity is an open incitement to anti-nature. Disdain for sexual life and sullying it with the notion of impurity, such is the true sin against the Holy Spirit of life.

When Allah created the earth, said Father, he separated men from women, and put a sea between Muslims and Christians for a reason. Harmony exists when each group respects the prescribed limits of the other; trespassing leads only to sorrow and unhappiness. But women dreamed of trespassing all the time. The world beyond the gate was their obsession. They fantasised all day long about parading in unfamiliar streets.

Sex and Lies was first published in 2017, in French. The book triggered bitter discussion in Morocco, and there were many activists, sociologists and intellectuals who joined me in decrying the state of sexual freedom in our country. More books were published and debates were televised but the laws themselves saw no change. Instead, a series of scandals and arbitrary arrests was reported across the kingdom. In 2019 a famous actress was arrested for adultery after her husband reported her. A senior civil servant was caught in a Marrakesh hotel bedroom with his mistress, who, when the police arrived, threw herself out of the window. Worst of all, upon leaving a clinic in September 2019, the journalist Hajar Raissouni was arrested and, along with her doctor, charged with participating in a clandestine pregnancy termination and with pursuing sexual relations outside marriage. Raissouni, who at the time was working for a newspaper well known for its criticism of the status quo and whose family includes a number of high-profile figures in political Islamism, rapidly became an icon for the campaign for sexual freedom. Observing this proliferation of cases, the film director Sonia Terrab and I decided to launch our manifesto for those obliged to live outside the law. It seemed to us that the systemic hypocrisy prevailing throughout our country had to be exposed. Because, although sexual relations outside marriage are forbidden by law, they are nonetheless practised every day and by everyone, whatever their social background. Moroccans motto is simple: Do what you wish, but never talk about it. So Sonia and I rounded up our friends and our wider social circles; we called on artists, intellectuals and politicians, male and female. On 23 September, dozens of publications printed our manifesto, which had collected almost five hundred signatures.

Over the days that followed, more than twenty thousand people contacted us wanting to join our project. Thousands of women sent us their stories and, through them, we discovered the true scale of the situation. Humiliation at the hands of the police; backstreet abortions; mistrustful doctors refusing to treat women in emergency conditions due to fear of the authorities; and the violent arrests of people in cars and hotels. We discovered the degree to which the Moroccan people are sick of the injunction to lie about their private lives. The degree too to which our repressive laws are increasingly utilised arbitrarily to buy others silence, to blackmail unwelcome neighbours and to exact revenge on the perpetrators of any disservice. Many of Moroccos citizens have come to realise that the laws themselves are responsible for the shadow, the constant threat that holds them back. And they know too that its the poorest, the most vulnerable and the women in particular who pay the greatest price for this sexual repression, while the well-off are able to live their sex lives more or less as they wish.

This growing awareness gives me hope. Like young people across the whole region, in Algeria, Tunisia and Egypt, the young people of Morocco are hungry for freedom; they want to see their right to a private life respected. The battle goes on, more urgently than ever.

Lela Slimani

November 2019

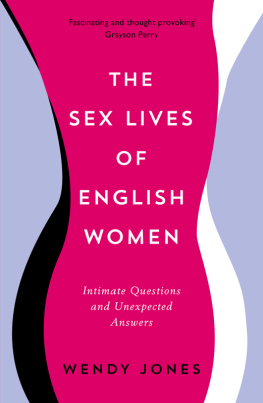

When, in the summer of 2014, I published my first novel, Adle, some French journalists expressed surprise that a Moroccan woman could write such a book. What they meant by that was an unconstrained book, a sexy book, a straight-talking, popular book, the story of a woman suffering from sex addiction. As if, by culture, I should have been more prudish, more reserved. As if I should have made do with writing an erotic novelette with orientalist shades, worthy scion of Scheherazade that I am.

Yet I feel that North Africans are well placed to take on themes relating to sexual suffering, frustration and alienation. The fact of living or having grown up in societies without sexual freedom makes sex a subject of constant obsession. Besides, sex is one issue thats well represented in contemporary North African writing. Its there in the autobiographical novels of Mohamed Choukri, in the poetry and novels of Tahar Ben Jelloun, in the novels and criticism of Mohamed Leftah and in the novels and films about gay life of Abdellah Taa. Erotic, even steamy, literature continues to be reinvented particularly among women, such as Lebanese writer Joumana Haddad and Syrian writer Salwa Al Neimi, whose novel The Proof of the Honey became a bestseller, following in the footsteps of the mysterious Nedjma, eponymous protagonist of the novel by Kateb Yacine.

So my first novel is in no way exceptional. I can even say its no accident that I created a character like Adle a frustrated woman who lies and leads a double life. Shes a woman eaten by regrets and by her own hypocrisy, a woman who steps out of line yet never experiences pleasure. Adle is, in a way, a rather extreme metaphor for the sexual experience of young Moroccan women.

*

When my novel was published, I insisted on doing a book tour around Morocco, to present my book in several of the countrys cities. I visited bookshops, universities and libraries. I accepted invitations from charities and support groups. The two weeks of my tour were a true revelation. I had never doubted the hunger for debate among those I was going to meet, but at every one of my encounters I was struck by how a discussion on the subject of sex enthused people, especially younger people. After the sessions, many, many women came up to me wanting to talk, to tell me their stories. Novels have a magical way of forging a very intimate connection between writers and their readers, of toppling the barriers of shame and mistrust. My hours with those women were very special. And its their stories I have tried to give back: the impassioned testimonies of a time and of its suffering.

My intention here is not to document a sociological study nor to write an essay about sex in Morocco. Eminent sociologists and brilliant journalists are already doing this employ one of their most potent weapons against widespread hate and hypocrisy: words.

*

Its important to recognise quite how brave the women who speak out in this book have been, quite how difficult it is, in a country like Morocco, to step out of line, to embrace behaviour that is considered unconventional. Moroccan society relies entirely on the notion of community dependence. And the community is considered by its members as both inevitable, a fate they cannot dodge, and a piece of good fortune, since they can always count on it for a kind of group solidarity. So our relationship to our community remains profoundly ambivalent. Another cornerstone of Moroccan society is the concept of hshouma, which translates as shame or embarrassment, and which is inculcated in every one of us from birth. To be well brought up, an obedient child, a good citizen, also means being alive to shame and regularly to demonstrate modesty and restraint. Harmony exists when each group respects the prescribed limits of the other; trespassing leads only to sorrow and unhappiness, Mernissi wrote. The price of transgression is very high and anyone guilty of crossing the