that she has touched.

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

M.F.K. FISHER , The Gastronomical Me, 1943

CONTENTS

Corby Kummer

Dmitras Lebanese Stuffed Grape Leaves, Hommus,

Tabbouleh, and Pita

Barrys Irish Dinner: Baked Fillet of Sole, Mashed Potatoes,

and Carrot-Parsnip Mash

Xotchils Venezuelan Asado Negro, Insalata

Repoyo, Pltanos, and Arepas

Sonis Indian Lamb Biriyani, Tali Machhi, Matur

Paneer, Bhartha, Roti, and Halwa

FOREWORD

CORBY KUMMER

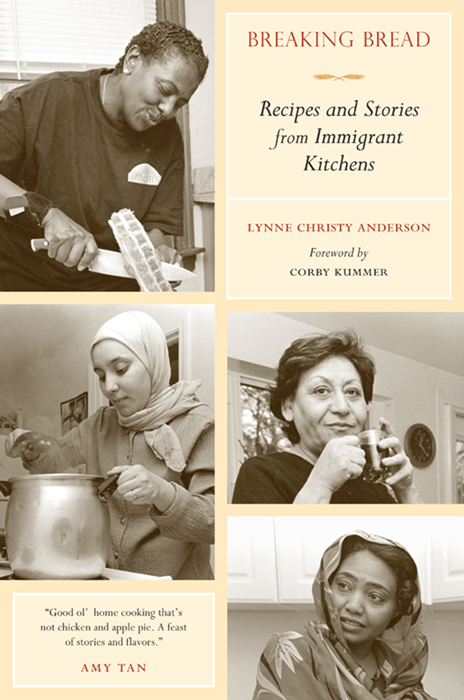

LYNNE ANDERSON LIVES IN MY neighborhoodJamaica Plain, a part of Bostonand is as proud of its diversity as I and the rest of us who choose to live here because of it. But my, what she found in our shared streets! A whole world of cooks, mostly women, living the cultures they came from at the markets I shop in and the kitchens I never see or even imagined were here.

But Anderson, a former professional cook turned teacher of immigrant communities, found them. Families recently arrived from Ireland, Greece, and Italy, traditional Jamaica Plain mainstays, and from countries that have a more recent but strong presence here, like Haiti, Cape Verde, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Brazil. And families from countries I had no idea were so close by: Sudan, Latvia, Morocco, Venezuela, Chile, Vietnam. Yes, she went looking. But I dont think her tour would be so difficult to take in most other large American cities.

Even if other cities might have international riches, though, they likely dont have any listeners and writers as gently sympathetic as Anderson. She went looking for more than interesting dishes most anyone can cook, though she gives us abundant, tempting, and accessible recipes. She also went looking for the meaning of home.

In her warm, subtly attentive interviewsthough she never mentions herself or her way of interviewing, you can sense her tact and acceptance of people just as they areAnderson listens for what is most important to a cook far from the place she grew up. That can be the way to knead pasta dough, the choice of curry stirred into a stew, the friendships formed with the only people who sell ground okra or the vegetables, fish, and cuts of meat that can best reproduce a memory.

And she listens for the language of the women (and a few men) who cook, usually with children or friends, to understand and show us how cooking and food form and forge lasting connections. As they tell Anderson about the lands they left and the lives they led then and lead now, the cooks become lost in their memories, as if the smell of a certain stew is the royal route to the kitchens and the people they most loved there. The actual circumstances that brought them to leave can be too painful to recount directly. It is hunting for mushrooms like they did in Latvia, or stuffing pork into soaked corn husks for Christmas tamales as in Costa Rica, or boiling beef and beets for a health-transmitting broth as in Vietnam, that lets them live again their childhoods.

Not that most of the cooks Anderson found left terribly painful pasts. Some did, and suffered for their beliefs or family circumstances they could not change. But most came here for opportunity, for education, for better lives for their children: the goals that have always driven people to emigrate. And most seem content with the new lives they have madeor, rather, they seem adaptable and resourceful, the necessary calling cards of the immigrant. Finding or improvising the tools and ingredients to reproduce remembered dishes, knowing how to handle food and the way to move in the kitchensubtleties and graces Anderson is alive towill endure displacement and disruptions, will literally keep families together.

This book of vivid, living memories can help you make memories of your own. Through the cooks Anderson presents, you can reproduce some of the elegance of a cinnamon-flecked Persian green herb omelet, the earthiness of Venezuelan roast beef with baked plantain and corn cakes, the surprising satisfaction of Irish baked sole with mashed potatoes (Be sure to use enough butter, a mother admonishes her tech-minded son via a video camera on his laptop screennaturally, given that the best butter in the world is Irish) and a carrot-parsnip mash. Best of all, you canwhatever your own family background, wherever you are nowlive a part of the American immigrant experience through Andersons words and the lives and food she celebrates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I WOULD LIKE TO THANK all of the people who invited me into their homes and so generously shared their stories and foods; I am greatly indebted to all of you. To Robin Radin, who accompanied me with her camera into kitchens, markets, gardens, and far-flung foraging sites, your photos add a depth to this book I could never have achieved with words alone. Special thanks go to my editor, Jenny Wapner, whose gentle guidance throughout the writing of the book has made it much stronger. I am hugely indebted to Cristina Rathbone, who first told me what I needed to do when I didnt have a clue. To Chuck Collins, who read numerous drafts of proposals and early chapters and came up with the books title, thank you. Thanks also to Elsa Auerbach, who has always been there as I tried to teach my way through Bostons immigrant communities, and to Vivian Zamel, who first made me think I could write. My dear friends Dana Burnell, Anna Brackett, and Tracy Strauss read drafts, gave me invaluable feedback, and never got frustrated with my endless editorial concerns. Alice Waters, Corby Kummer, Nikki Silva, Anna Lapp, and Nazli Kibria provided early encouragement for the book and helped to shore up my sometimes wavering optimism. Eva Katz, thank you for showing me how to write a recipe.