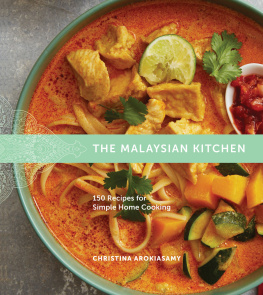

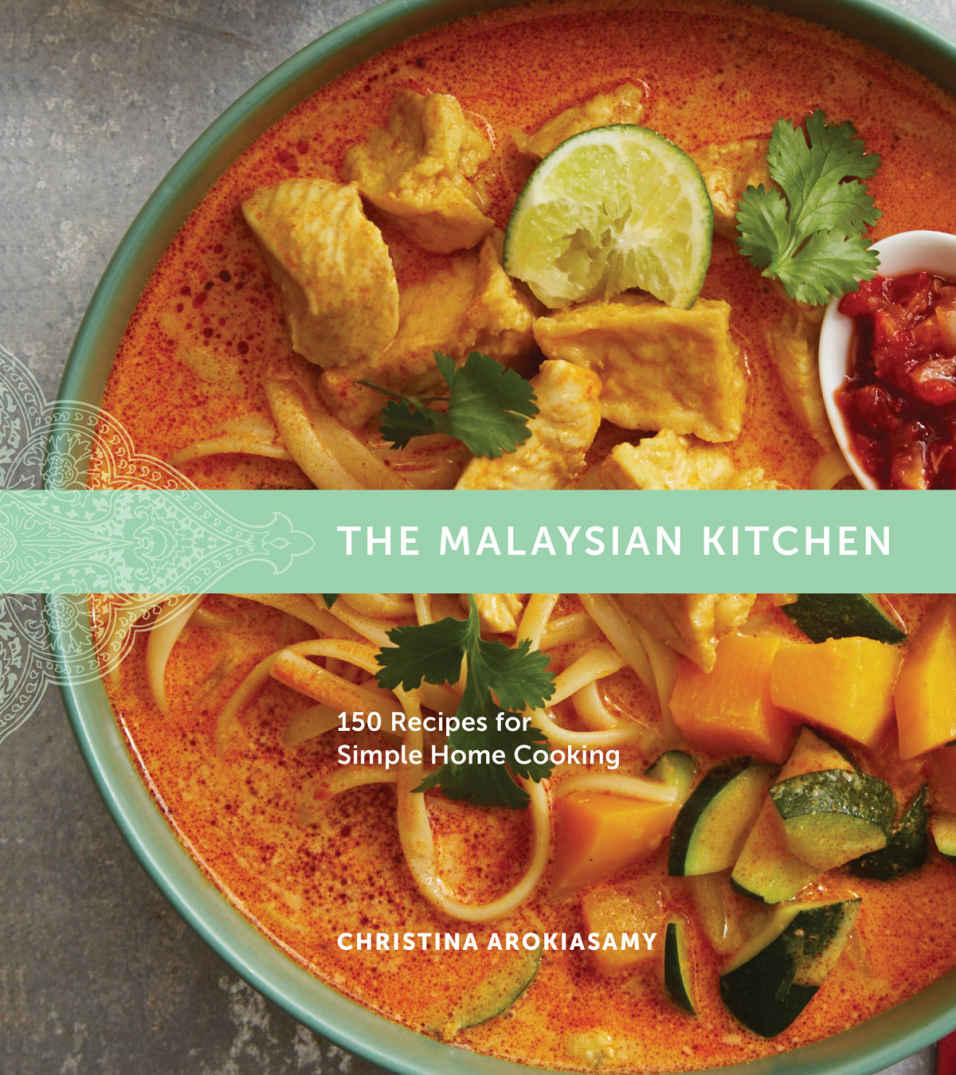

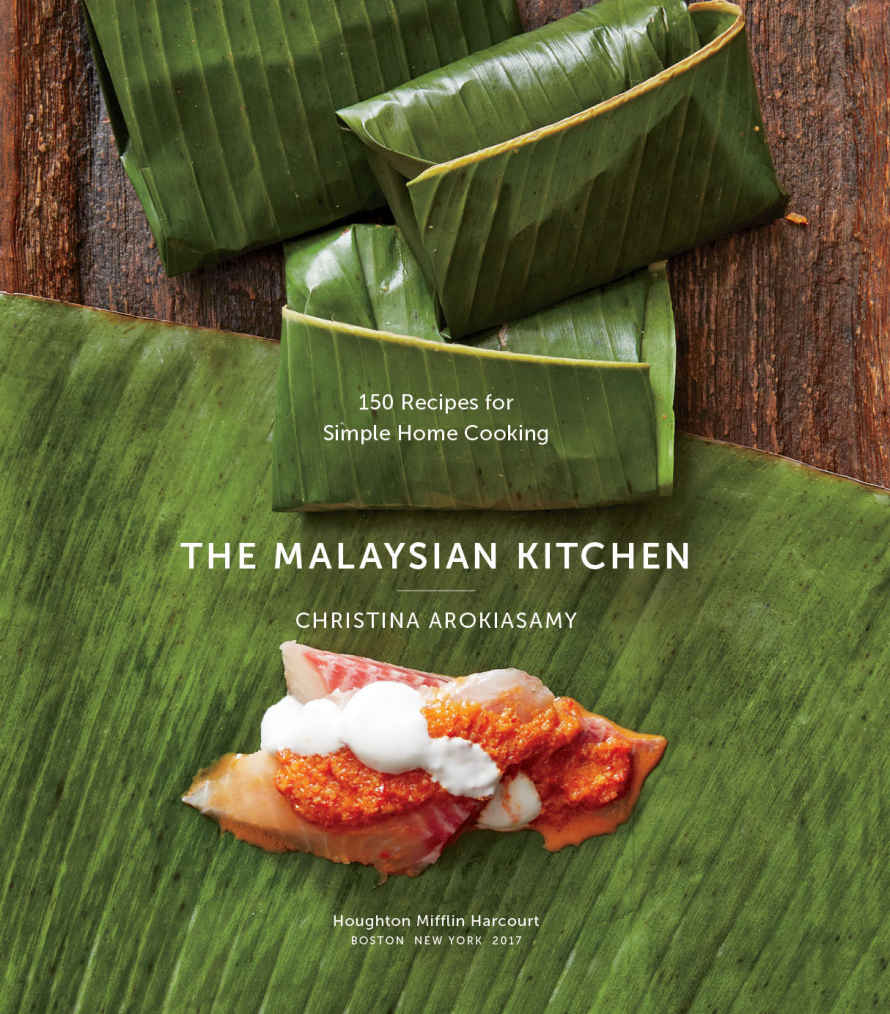

Copyright 2017 by Christina Arokiasamy

Food photography 2017 by Penny De Los Santos:

Pages

On-location photography 2017 by David Hagerman:

Pages

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-80999-4 (hbk)

ISBN 978-0-544-81002-0 (ebk)

v1.0217

This book is dedicated to my mother of blessed memory, Rosalind Francis, for without her I would not be here

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I recall 22 years ago, when I migrated to the United States. I invited a few of my neighbors over to my apartment in Hawaii for a simple Malaysian dinner of beef rendang with coconut rice, mango and cashew salad, a bowl of sambal belachan on the side, and a baked pandan custard cake for dessert. I will never forget my neighbors praise and the way they devoured the dishes with gusto.

And so I agreed to walk my new American friends through a series of cook-along dinners. The six of us would cram ourselves into my tiny kitchen, and I would teach them the under-pinnings of Malaysian cuisine with ingredients that they might never have seen nor heard about.

Although I had a fair collection of cookbooks and had spent loads of time browsing through food magazines to feed my growing interest in upgrading my culinary skills, I had never taught anyone to cook. Before coming to America, my time was spent as a chef in the professional kitchens of Thailands and Balis Four Seasons resorts. Any vacation time I had was spent learning in the kitchens of the Wandee Culinary Institute in Thailand, as I wanted so much to embrace the cooking traditions of the neighboring Southeast Asian countries. During my journey, I was often surprised to find similarities to the dishes that I cooked with my mother in our home in Malaysia.

In preparation for my very first cooking class in my little Hawaiian apartment, I placed the three sisterscinnamon, star anise, and clovesin small bowls on an old bamboo tray alongside fresh lemongrass, galangal, makrut lime leaves, ginger, and other aromatics. Tamarind and colorful bottles of seasoning sauces from my cupboard were neatly arranged on the table. My friends were surprised that even before we began cooking the aromas of the ingredients filled the apartment. After introducing them to the three sisters, I begin to saut the spices in hot oil to release their flavor. A sweet aroma permeated the kitchen and the entire apartment. I love cinnamon sprinkled in my hot chocolate and in my desserts, my neighbor Karen commented, but have never used it in meat dishes. This is incredible. As the beef rendang continued to cook, she inhaled the spices wafting from the pan.

That moment of sharing reminded me what a big part cinnamon played in my own world. I was transported back to Malaysia, where beautiful scents infused my life. My mother was a spice merchant, and my familys colonial home was surrounded by spice trees. I recall that during harvest time, the morning air carried a whiff of spice as the dark almond-shaped cinnamon leaves brushed against my window, delivering a sweet fragrance. I enjoyed watching my mothers seasonal workers with their wrinkled hands skillfully selecting and cutting off the best parts of the bark of the cinnamon trees with special knives. They stacked the moist bark sheets, painstakingly rolled them into long pipes, and left them to dry in the sun. After the pipes had completely dried, the workers cut them into those short sticks that the rest of the world knows as cinnamon. For us, cinnamon was not just a spice; it was a way of life, infused in our food, in our medicine cabinet, and even arranged in vases as decoration. The aromatic brown sticks were sauted in hot oil to add a savory flavor to our pot of chicken curry or to boost the veggie pilafs and lamb biryanis. Mid-afternoon, several quills of cinnamon were brewed with Ceylon tea leaves, making a long delicious thirst quencher for the hot afternoons. I can clearly remember my father placing ground cinnamon in small glass bottles in his medicine cabinet, so he could later create brews to relieve muscle aches, cold, flu, and stomach upsets and to maintain cardiovascular health.

Our yard was a place where you experienced food with your eyes and your nose before your stomach. Among the cinnamon, mango, and curry leaf trees were plenty of ginger root plants, with their blindingly green leaves and scarlet flowers. We blended fresh ginger with garlic as building blocks to begin most of our Malaysian dishes. Fresh ginger was also dried under the tropical sun and ground into a citrus-scented powder used in marinades, salad dressings, desserts, and tea. The subtle green-tea scent of the pandanus palm pervaded our garden, tinted our rice cakes pale green, and infused our custard with sublime flavors.

Central to all this was the kitchen. Like most Malaysian homes, the kitchen was divided into two areas: The dry kitchen was much like the Western kitchen except that it was rarely used for cooking. Rather it was a place for storing plates and cutlery for day-to-day use. More importantly, it was a home for spices such as coriander seeds, fennel seeds, star anise, turmeric, and chili powders, stored in large bottles along with other pantry ingredients. An old wooden bench made a lovely spot for resting. The wet kitchen was where the women gathered, holding onto the bonds of tradition, and working to create masterpiece recipes for the family. This part of the kitchen was a hive of activity: the pounding and grinding of spices into a wet paste; the washing and cleaning of aromatics, vegetables, fish, and meat; the enthusiastic chatter and the din from the clanging of utensils. Whenever we cooked a sambal with chilies, red shallots, and shrimp paste, or had a pot of laksa bubbling away at the stove, the spicy scent would announce to passersby and neighbors that lunch or dinner was being prepared. For most Malaysians, this was an invitation to interact with the neighbors and perhaps share some spicy stories or take a glimpse at what was cooking next door. The wet kitchen was where I first learned to cook.

Food has been an important part of my family for generations. My father would often bring friends home unannounced, and my mother was able to magically prepare a variety of dishes to please the guests. I saw her re-purpose everything and create dishes with whatever ingredients she had on hand. My mother, taught me the details of spice grinding, how to work with the ingredients, and how to smell, feel, and taste the food. But she never concerned herself with quantities and cooking times. A touch of this and a dash of that was the way she cooked without ever using measuring cups or spoons.