Like many other financially successful tycoons from New England and the Midwest, Edward Drummond Libbey, who had turned a small family glass company in Toledo, Ohio, into the industrial giant Libbey-Owens-Ford, ventured to Southern California in search of a second home in a more temperate winter climate. Since first visiting it in 1908, he had taken a shine to the Ojai Valley, a picturesque agricultural community east of Ventura, eventually purchased a significant amount of real estate there, and in 1914 proceeded to develop his vision for rebuilding the town of Ojai as a romantic Spanish Colonial Village.

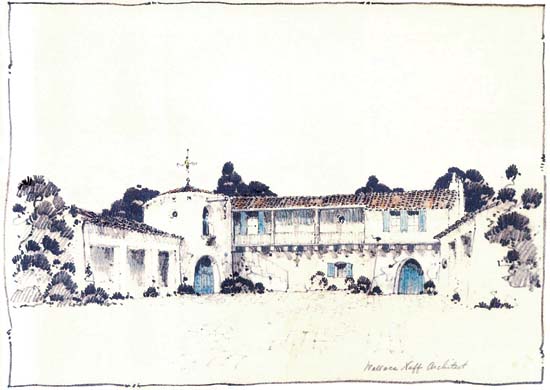

Libbey was already acquainted with the more established architects practicing in Southern California and had hired some of them for various projects, including Myron Hunt and Elmer Grey, George Washington Smith and Richard Requa, who assisted Libbey in planning and redesigning downtown Ojai into the architectural center it is today. Wallace Neff, a young Pasadena architect who had opened an office in Ojai a year after acquiring his license in 1921, may have been the new guy on the block, but Libbey hired him in 1923 to design the Ojai Valley Country Club and Hotel and, while he was at it, a stable building for Libbeys own estate.

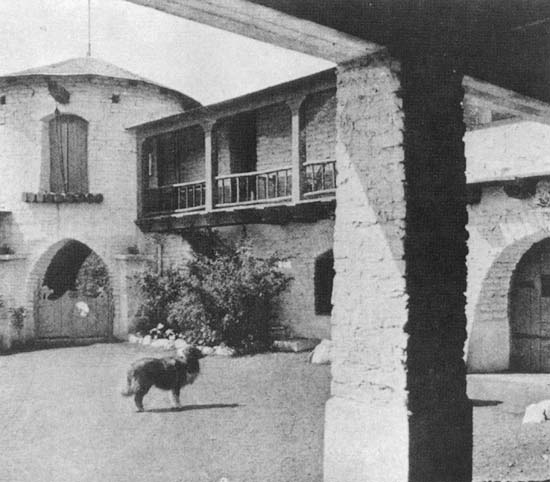

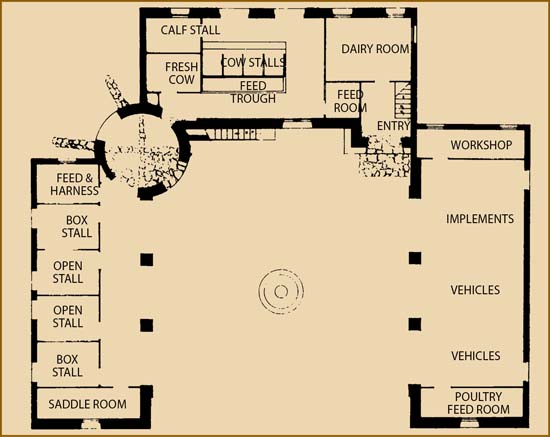

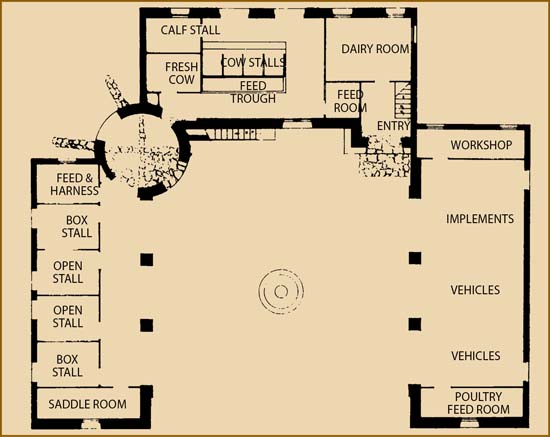

Neffs architectural bent, no doubt encouraged by his clients enthusiasm and vision, tended toward a regional but eclectic aesthetic. The design for the stables in particular, although rustically Mediterranean, also owes a debt to some French farm fantasy. The adobe structure is definitely a utilitarian, vernacular building, but it is whimsically inspired as well by something out of the French countryside. As one can readily see from the original plan and photos that were published in 1924, this brand new building suggested a kitschy spirit that was working hard to convince us that it might have descended from pioneering immigrant farmers from France who had settled in Ojai decades ago.

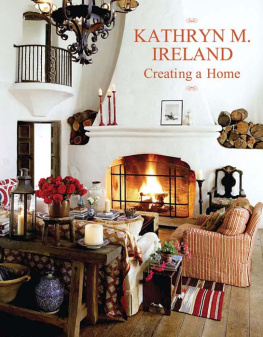

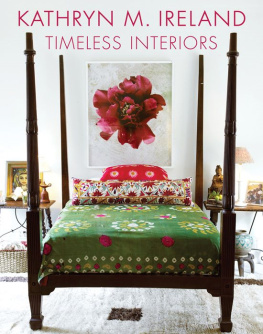

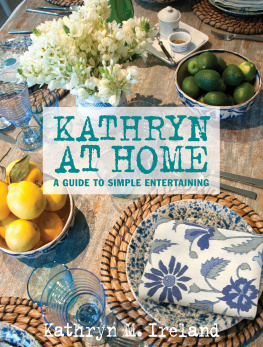

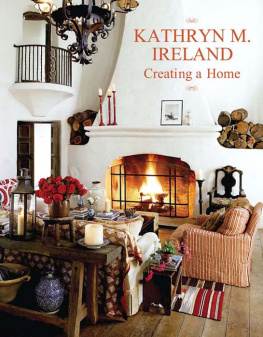

When one adds eighty years of age to the original building, including the subsequent remodeling and additions to the compound designed by the architect Austen Pierpont in the 1930s, and several eventual occupations by people rather than farm animals who were now making the stables their home, it is easy to accept that by the time designer Kathryn Ireland finally saw it in 2003, the property had indeed acquired some real history as a regional landmark. The fact that it was a bit of a shambles when she encountered it only added to its appeal. And so the stables began yet another life under the designers direction, but this was not to be the typical renovation.

One of the inevitable characteristics of most projects designed by professionals (and this appears to have been true of the original Neff product) is that they are neatly finishedthey are of a piece, in a word, done. Often they are so perfectly complete that ones soul cannot enter in. There are no fissures or cracks, no worn surfaces or rough spots that would make one feel they could trespass comfortably and make it theirs. Kathryn Ireland is not of this school. She revels in the rough spots. If you have ever been privileged to visit her home in the South of France near Montauban, you can instantly appreciate her aesthetic inclinations. Her farmhouse there, like the Libbey stables, was a ruin when she found it, and, although much more marvelously comfy and functional now after her makeover, its great attraction and accomplishment, ironically, is that it is still a bit of a ruin. Kathryn has that rarest of abilities to know when to leave well enough alone and savor rather than despair the thing that is not quite finished.

When Kathryn first called me to look at a property she had found for sale in Ojai, I was doubtful. There are times when I imagine my friend was born into the wrong era. She always seems unreasonably ebullient, keen and excited about many things the rest of us take for granted. Although I pretend always to join in her Gatsby-esque enthusiasm (how can one not?), I secretly maintain a healthy skepticism nurtured, perhaps, by too many years of architectural practice. Kathryn often seems like a giraffe with her head gliding through the treetops while the rest of us intently scan the ground at our feet for impediments. So when I first saw the Libbey property, it appeared to be not only a ruin but an incredibly impractical, money pit of a ruin that would take too much time, effort, bureaucratic negotiating and dollars to salvage. I advised her accordingly and suggested a healthier alternative would be for her to get over her fixation for the ruins prospects and move on to an easier opportunity.

Something else I am always learning about Kathryn, however, is never to underestimate her stubbornness once she gets hold of an idea. The combination is an anatomical stretch, but, low and behold, there is a bulldog inside that giraffe! As I consider now what she has accomplished with the place, happily presented in the pages of this book, I must question altogether my initial skepticism and cant help but cheer her forward to the next seemingly impossible or impractical challenge.

I also realize that a significant characteristic of her special talent is being able to recognize that a part of the design challenge is to leave some of it undone. When she refers to the attractions of the worn ruin or the patina of age and use, these are not the usual aesthetic pretensions towards some nostalgically perfect re-creation of age but the rough and tumble facts of our lives, which usually work against perfection. Perhaps it is her experience raising three sons; perhaps it is her own nomadic background or her festively impatient spirit. Whatever it is, she knows that not all designed houses are homes, and we are grateful and full of admiration for what she does (or undoes) and how she does (or undoes) it. Very few people in her industry have her innate understanding of why it matters to celebrate history with all its imperfections, and that interior design, like cosmetic surgery, can be a risky business when perfection is the predominant goal.

Introduction & History

of the Libbey Ranch

I love a good ruin. Whether its a sagging barn, a broken bicycle, a jilted bachelor, or a curdled bearnaise, bringing something spoiled back to life has given me great satisfaction and pleasure from very early childhood. Well-mended Coalport porcelain, imaginatively resewn Irish tabletop linens, and reinhabited stone fishermens cottages with brightly painted shutters continue to give me great joy all these years later.