For Rich, who never licks the spoon, and Alex,

who never misses an opportunity

And for Patricia and all the lessons I learned in her kitchen

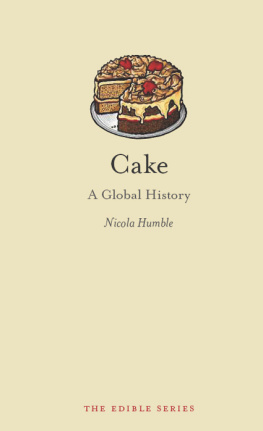

What is a cake? You might think that the answer is so obvious that we dont even need to ask the question, but this established teatime treat has stirred up more controversy than you might at first imagine. So before we embark on our social and cultural history of cake, we had better get our definitions straight. In 2014 the British tax body HMRC took Tunnocks of Scotland to court. Tunnocks make that beloved British treat, the tea cake: a glossy chocolate-coated dome of marshmallow atop a solid biscuit base, all wrapped in distinctive silver and red foil. On this occasion HMRC were more interested in their Snowballs, however, which are close cousins with the tea cakes and consist of globes of mallow, coated in chocolate and covered in coconut. The problem was that Tunnocks described their Snowballs as cakes. HMRC, meanwhile, felt that they were more properly a biscuit. The reason that this was so contentious is that while chocolate-coated cakes are zero rated for tax (the seller doesnt charge value added tax on sales but can recover any VAT it has itself incurred), a chocolate-coated biscuit is standard rated. One can see how the trouble arose; HMRC had already waded into these waters twenty-three years previously, when it tackled McVities over the categorisation of their Jaffa Cakes (according to the McVities website, the original combination of light sponge, dark crackly chocolate and the smashing zingy orangey bit the latter a layer of firm jelly which can be pleasingly revealed by teasing off the upper chocolate layer with the teeth). HMRC lost on that occasion for three principal reasons. First, the Jaffa Cakes ingredients are those of a cake (egg, flour and sugar), and the batter which is used to make them is thin and not thick. Second, their texture is like that of a cake they are soft and friable (crumbly, in other words) rather than crisp and brittle. However, the most famous part of the ruling as far as British trivia goes was the third point: that Jaffa Cakes go hard when stale like cake rather than soft like biscuits.

HMRC were to lose in 2014 too. This time, however, the ruling was based on a different set of principles and is worth quoting, as much for amusement as for instruction:

A Snowball looks like a cake. It is not out of place on a plate full of cakes. A Snowball has the mouth feel of a cake. Most people would want to enjoy a beverage of some sort whilst consuming it. It would often be eaten in a similar way and on similar occasions to cakes; for example to celebrate a birthday in an office. We are wholly agreed that a Snowball is a confection to be savoured but not whilst walking around or, for example, in the street. Most people would prefer to be sitting when eating a Snowball and possibly, or preferably, depending on background, age, sex etc. with a plate, a napkin or a piece of paper or even just a bare table, so that the pieces of coconut which fly off do not create a great deal of mess. Although by no means everyone considers a Snowball to be a cake, we find that these facts, in particular, mean that a Snowball has sufficient characteristics to be characterised as a cake.

There is something rather wonderful about the picture of a bench of learned appeal lawyers coming to such a precise decision about something as frivolous as a snack (they noted that they tasted a range of similar confections in moderation in the process of coming to their decision). But their words are actually rather interesting. The Jaffa Cake ruling was based on ingredients and the way the cake behaved after baking (whether it went soft or hard). What the judges in the Snowball case chose to dwell on, however, was the occasion on which cakes appear: birthdays and other celebrations, as part of a sit-down occasion, not as street food, at a time when they can be savoured. The report of the 2014 appeal at a tax tribunal listed seven key traits which legal precedent had established as important in distinguishing cake from biscuit: ingredients, manufacturing process, unpackaged appearance (including size), taste and texture, circumstances of consumption (including time, place and manner of consumption), packaging and marketing.

However, there is clearly some room for manoeuvre here too. Jaffa Cakes do not have the traditional appearance of a cake: they are flat and, to all intents and purposes, biscuit-like. A Snowball, meanwhile, is not baked, and does not contain flour; meringues have also been accepted as cakes as far as tax law goes. The tribunal judges agreed that Snowballs did not have all of the traits of a cake, but they had enough. So going back to our opening question: what exactly, then, makes a cake a cake?

This book answers that question. Over the course of its chapters we find that the Snowball judges were correct: its about occasion as much as ingredients. We also see that cake is a treat in some way, not often part of a meal, but central to the ties that bind families and communities together. It signals hospitality and welcome; not offering cake to a guest is a way of keeping a visit short. Even in the long-ago past, sweetness and occasion marked it out in subtle ways from bread. Its not vital, of course; no one is claiming that cake has a foundational part in the human diet. But that said, if we strip back the layers of icing, if you will, we see that to understand what cake is and what it means to us both now and in the past, we need to deal with a good number of themes which are very important indeed: the spread of international trade and the opening up of the New World (sugar and spices); the transnational migration of people (how cakes travelled and were transformed); the history of female domesticity and emancipation (the gendered nature of baking and how that is breaking down); the importance of appearances cake as art; and the rise and cementing of national traits and pastimes, to name but a few.

For many people, cakes mean memories, almost always of celebration, family and love. Because they are fairly cheap to buy and easy to make, cakes are both accessible and familiar to most in the Western world. They have played their parts in social occasions and treats for centuries, and in many different forms and tastes. In all these settings, however, cake has always carried a symbolism far in excess of its nutritional importance or, for a long time, its monetary value. For centuries cake has gone hand in hand with weddings, birthdays and funerals; it has accompanied small children to school in lunch boxes and tuck boxes; it has said I love you, congratulations and Im sorry. A be-candled cake carried in to a party marks someone out as special and its bearer as a nurturing and loving provider. A homemade cake is one of the most nostalgic (and oftentimes unrealistic) emblems of motherhood and domesticity, and one of the reasons that many people feel so attached to family recipes and cakes which are trotted out on regular occasions. Other family memories are built on shop-bought confections a Battenberg, a Lamington or a Twinkie is less likely to be part of a home bakers repertoire than a simple sponge (certainly the Twinkie, with its list of unfathomable ingredients) but many people will still sigh nostalgically at the sight of the pink and yellow squares, the coconut covering, or the soft yellowy sponge in its plastic wrapper. Cake is more than a foodstuff: it is the stuff of happy memories and a comfort as well as a sugar fix to get you through the afternoon.

Next page