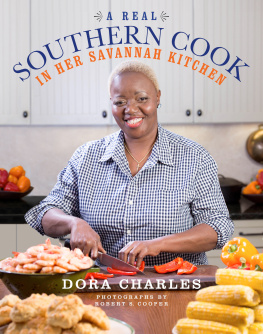

Copyright 2015 by Dora Charles

Photographs copyright 2015 by Robert S. Cooper

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Charles, Dora.

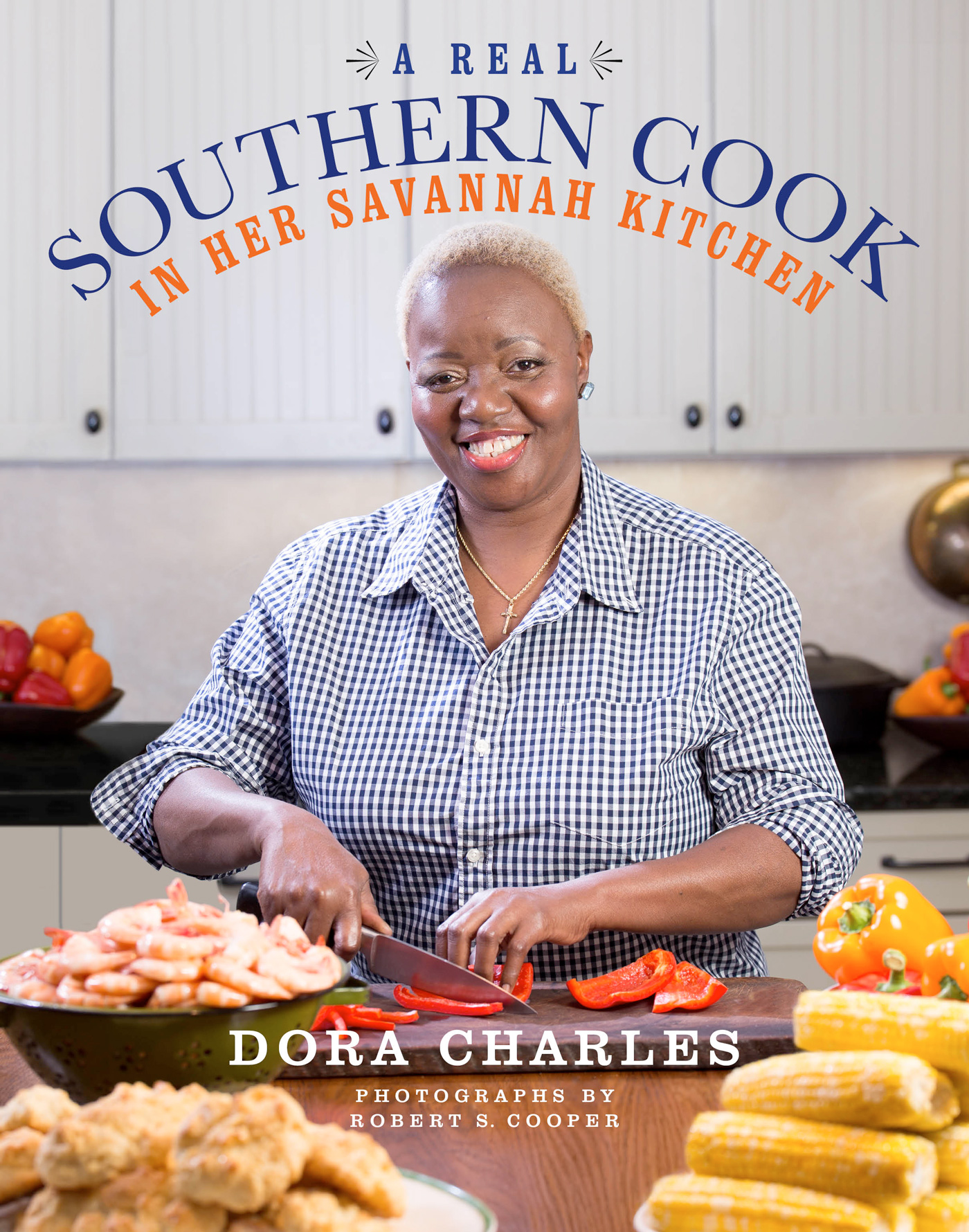

A real Southern cook : in her Savannah kitchen / Dora Charles ; with Frances McCullough ; photography by Robert S. Cooper.

pages cm

Includes index.

A Rux Martin Book.

ISBN 978-0-544-38768-3 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-544-38577-1 (ebook)

1. CookingGeorgiaSavannah. 2. Cooking, AmericanSouthern Style. I. McCullough, Fran, date. II. Cooper, Robert S., date. III. Title.

TX715.2.S68C487 2015

641.59758724dc23

2015010770

Book design by Jennifer K. Beal Davis

Ebook design by Rebecca Springer

Food styling by Erin McDowell

Assisted by Sarah Daniels

v1.0915

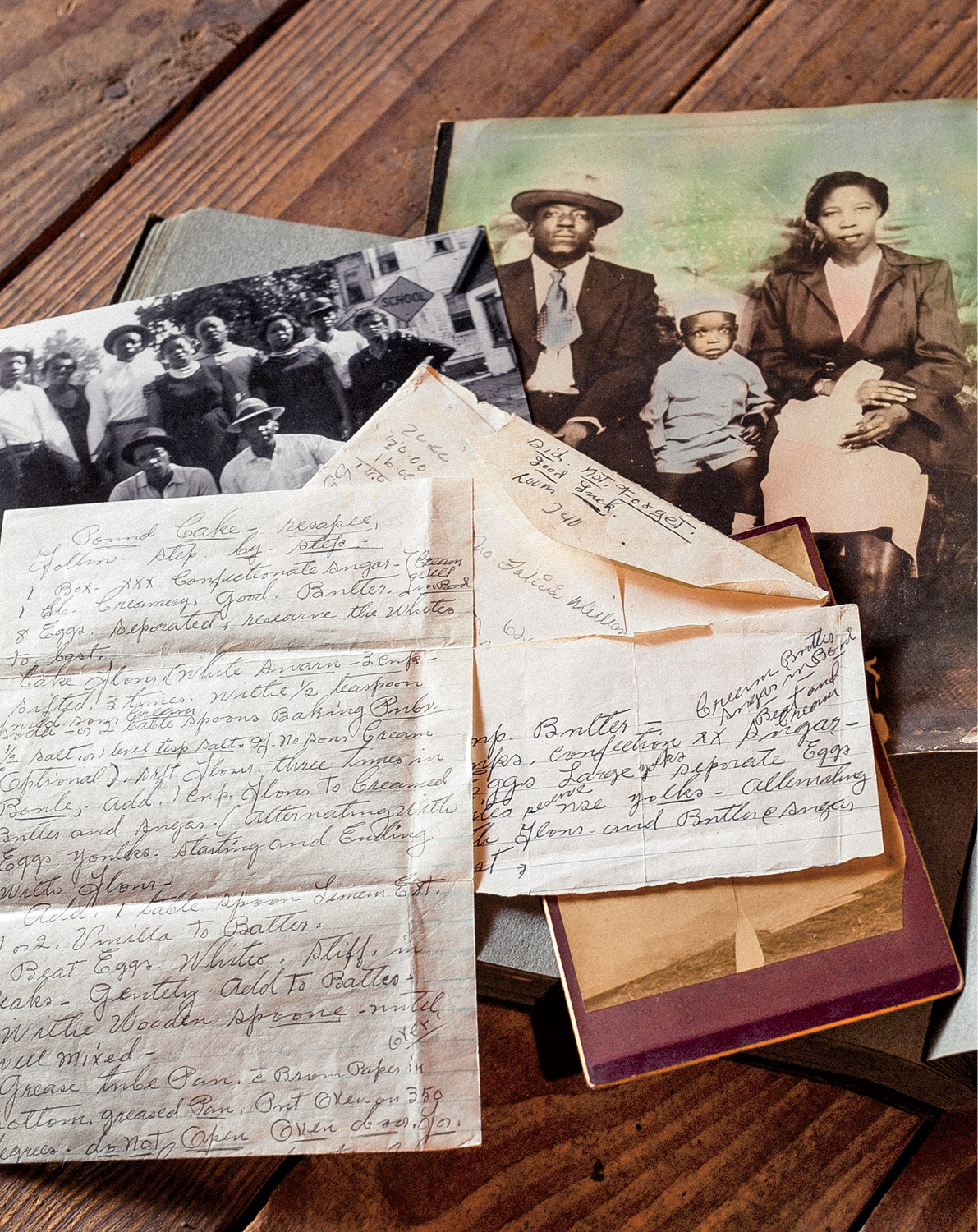

finding my way

The only mother I ever knew was my grandmother. My mother died when I was just a year and a half old, and my Daddys mother, a wonderful woman named Hattie Smith, left her home in the country and came to live with us in Savannah. By the time I can first remember things, Daddy was married to my stepmother, Sallymy brother and sister and I called her Sexyand eventually they lived upstairs in the beautiful Victorian house in Savannahs historic district that hed been smart enough to buy for $15,000 in the mid-1960s. That house on East Duffy Street had fifteen rooms, which was a good thing, because there was plenty of room for all of us, including Sexys grown children when they visited and sometimes my half-sisters, Marilyn, Hattie, and Lilliemae, and the half-brothers Skeeter and Thads. Daddy said no one was half of anything and we were all sisters and brothers in the same big familyand he took good care of all of us.

I was the baby in the downstairs family with my grandmother, and I always wanted to be like her. Shed had fifteen children of her own, all born at homeonly ten survivedwith just a spoonful of corn liquor to get her through the deliveries. She was sweet and kind, but also firm and to the point. She wore an apron all the time and never came out of the downstairs kitchen if she could help it. We ate at her table and were generally her responsibility, even though Daddy was head of the household. She was a church lady, and she didnt play with us, but she did see that we always went to church with her.

Sometimes there were potlucks on special days, and she would bring covered dishes. Those were some eye-popping feasts they laid out. People always looked out for my grandmothers food, and we were proud of her. Everyone knew her fried chicken was the crunchiest on the outside and the juiciest on the inside, with just the right spices to bring it to life. Her baked beans were like no others, so deeply flavored and satisfying they were almost a meal in themselves. And her sweet potato pie was a legend then and still is today, when I make it for all my family and friends at Christmas.

the old days in the country

There was no stopping for pain or blood; you had to keep working until there was no more sun in the sky.

In fact there was always a fabulously good cook in my family, going right back to slavery, when both sides of my family labored on plantations in the Lowcountry, the coastal area of South Carolina and Georgia. The women were house slaves, so their skills in the kitchen spared them the cruel work in the fields from dawn to dusk. We grew up hearing the stories of slave times, and the tales of the cotton harvest, when my great-grandfathers hands got so tender theyd bleed, stick in my head todaybut there was no stopping for pain or blood; you had to keep working until there was no more sun in the sky. The Emancipation Proclamation and, much later, the boll weevil finally put an end to those labors, but the family went on to farm as sharecroppers, working just as hard plowing and growing corn, tomatoes, and peas. Almost all of the crops and the money that came from themtwo thirdswent back to the landowners. My father, who was born in 1918, worked those fields too, and he had to drop out of school before he learned to read or write to help out with the crops.

Only one of my fathers nine brothers and sisters survives today, and thats my Aunt Laura, eighty-three years old, who lives in Savannah too. Her stories of growing up on the sharecropping farm are vivid. The farm was in Blackwell, Georgia, about five miles from Monticello, one of the biggest cotton-growing areas in the South.

My family grew cotton, corn, tomatoes, peas, and even cane. They made their own cane syrupits the maple syrup of the South. They had two cows and some pigs and chickens. They churned their own butter and made their own lard. They picked their own apples, peaches, and pears and knew where to find all the berries and other wild fruit and nuts. They cured their own bacon and hams. They grew sweet potatoes and white potatoes, peanuts, cabbage, greens of all kinds, carrots, and beans, even lima beans. My grandfather and the boys fished and hunted for ducks, rabbits, squirrels, and possums. A big treat was possum and sweet potato dinner, though Aunt Laura hated it and refused to eat it. The possum would be soaked overnight in vinegar to take the wildness out of it, and then it would be roasted, surrounded by sweet potatoes.

There was a huge kitchen in the farmhouse, and one year my grandmother canned more than a thousand quart jars from her own garden, so many that my grandfather had to add new wooden shelves up to the ceiling. The water was spring water, lugged up the hill by the children before they went to school or out to the fields in the early mornings. The family was really poor, but the food was so delicious that they often ate like kings. All the sharecroppers helped each other out, traded produce, and shared what they had. Although they could never seem to get ahead, always owing the bosses rent or money for seeds or fertilizer or flour or something else they had to get at the company store, it was a warm community that made its own funtelling ghost stories, singing, and passing along tales from the old days. Aunt Laura remembers a very old woman who had been a slave coming over sometimes to talk to my grandmother about slave days. Little Laura would run and hide under the bed when she came because she looked like a witch and talked about very scary things, like the story of a child being traded for a pot of cane syrup.