In memory of

Vera, Viktor and Lyusia

Contents

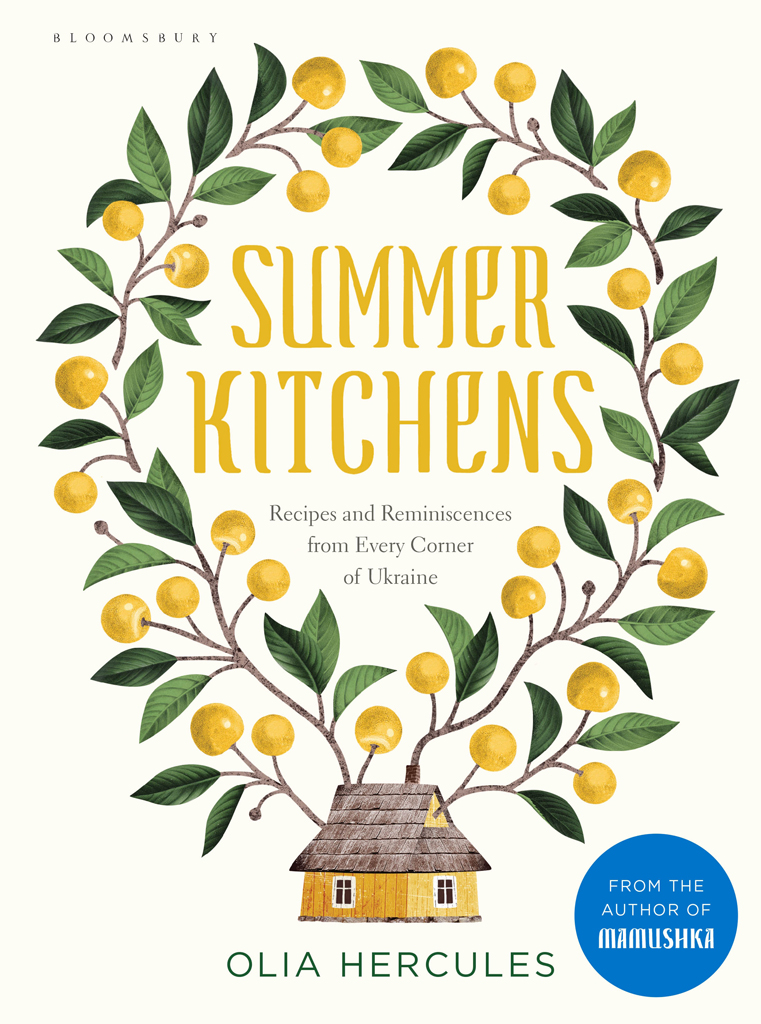

The summer kitchen

This cookbook is not just about cooking in the summer. It is about a very special place, the perfect prism through which to look at Ukraines culinary culture in all its regional, climatic and seasonal diversity.

I grew up in the south of Ukraine, in a small town called Kakhovka. Apart from having a regular kitchen indoors, we had something else: a separate little house, nothing glamorous just a one-room brick structure, which we called litnya kuhnia, summer kitchen. It was situated in our courtyard, closer to the place where we grew our fruit and vegetables, and was a natural and unremarkable part of our lives.

I live in London now, with hardly any space for a shed, let alone a summer kitchen, but the memory of having a separate cooking-workshop space makes me feel as though back then we had more luxury than we thought. It was only when I very casually mentioned summer kitchens to my friends here that I realised they were actually a bit of a phenomenon, quite idiosyncratic and magical. I was suddenly burning to find out more about this tradition. Little did I know that the summer kitchens story would turn out to be even more interesting than I could have imagined.

To clarify, these were more than the outside spaces you find in some hot countries, where people cook al fresco under an awning. They were separate buildings with the main purpose of being a kitchen. People cooked and ate there all summer, and sometimes used them to prepare bigger feasts in winter as well, especially during festivities.

Summer kitchens probably started as an extension of dugout barns called zemlyanky, where animals were kept and people sometimes lived as well. Some of the ones I visited were largely unchanged from the day they were built. The materials they were made of varied from region to region, from brick and shell rock in the south, to wood or clay in central and north-western Ukraine. The local names changed too: they were known as budka (cabin) in south-eastern Besarabia and shopa (barn) in north-western areas.

The reason summer kitchens exist at all is because of the climate. Ukraine is often associated with Russia, and has a reputation for being cold, snowy and harsh. But it is also huge, with a wide range of climates. And in summer, which I remember coming early during my childhood, we would often say that it was hot enough to crack the flagstones asfalt repayetsa, in the local dialect.

Warmed by the blazing sun and ancient humus, Ukrainian soil is some of the most fertile in the world. Called chornozem, black soil, it has also been known as black gold. In the 1940s, the Nazis allegedly attempted to transport trainloads of this precious soil to Germany, and since the 1990s, following the break-up of the Soviet Union, it has become a black market commodity.

In the years after World War II, when things were improving slightly, the following scenario became common. Imagine a scorching-hot Ukrainian summer in the mid-1950s. A young couple would get married. What made sense for them to do, especially in rural areas, was to start with a small building, containing a makeshift bed and a kerosene stove it was both a bedroom and a place where the meals were cooked. Sometimes a couple might already have children by the time they acquired land of their own, so the whole family would stay in this bedroom-kitchen. If there was a craftsman in the village, a large masonry oven called a pich would be built into it.

Their whole life and livelihood would sprout up like mushrooms around this modest structure. Normally it would take six warm months to build the main house, sometimes a year or even longer. During this time, the couple would be planting an orchard and a vegetable patch too. They wouldnt always work on their own. People in the village, sometimes as many as fifty, would come and help out, bringing hay to construct the walls of the khata (Ukrainian clay and straw house), singing as they went. All they asked for in return was some lunch and dinner, and perhaps a similar favour in the future. Once the main house was completed, the family would move there, and the small, interim house would become the summer kitchen.

When my mother was a child, in the early 1960s, my grandparents bought a three-bedroom house. The summer kitchen, an essential feature in their eyes, was missing, so my grandfather Viktor decided to add it on, as an annexe to the main house. But just near the very spot where it felt most natural to build it was a mature yellow cherry tree, and one of the main branches, as thick as a thigh, was firmly in the way. Viktor, the gentlest man, loved the tree so much that he could not imagine cutting this branch off.

What he did next was extraordinary: he simply built the branch into the kitchens structure. So there was this massive tree branch going right through one of the walls and sticking out of the roof. Now you might think that he must have been an eccentric kind of guy to tackle this mad and dubious construction manoeuvre. But in my travels around Ukraine I have discovered other families with equally quirky summer kitchens, born of a similar ethos it seems to me that the underlying intention is to try and live in harmony with nature, with gratitude to the land and what it gives you. Summer kitchens encourage a very intimate, almost spiritual connection to everything living around you.

Remember that, during my grandfathers day, we were still in the Soviet Union. And even though I was the child of 1980s perestroyka, which heralded big changes, I still remember empty shops and long queues to pay the electricity bill or buy mayonnaise (a collective obsession). But unlike people in Moscow and other cities, who had little opportunity to grow their own produce, rural Ukrainians were able to nurture a way of life that historically had served them best husbandry. So at the time a summer kitchen was not just some romantic idea, as it might have become now. It symbolised the core, the backbone of life; it was both a place of hard graft and a sanctuary.

Summer kitchens were practical. In summer the heat could be intense and there was rarely any air conditioning, often not even extractor fans. To have a separate place where frying, cooking and preserving could be done was very handy. Apart from everyday and festive cooking, summer kitchens were where all the fermenting, pickling and preserving happened, on an almost industrial scale, come September. Pick your fruit and vegetables by the bucketful, carry them into the summer kitchen and start the mammoth pickling operation, leaving the doors and windows wide open.