Also by

Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene

and from McFarland

Women, Art and the New Deal (2016)

Winifred Black/Annie Laurie and the Making of Modern Nonfiction (2015)

Seeing the American Woman, 18801920: The Social Impact of the Visual Media Explosion (Katherine H. Adams, Michael L. Keene, Jennifer C. Koella, 2012)

Women of the American Circus, 18801940 (2012)

After the Vote Was Won: The Later Achievements of Fifteen Suffragists (2010)

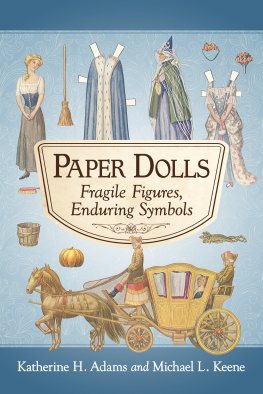

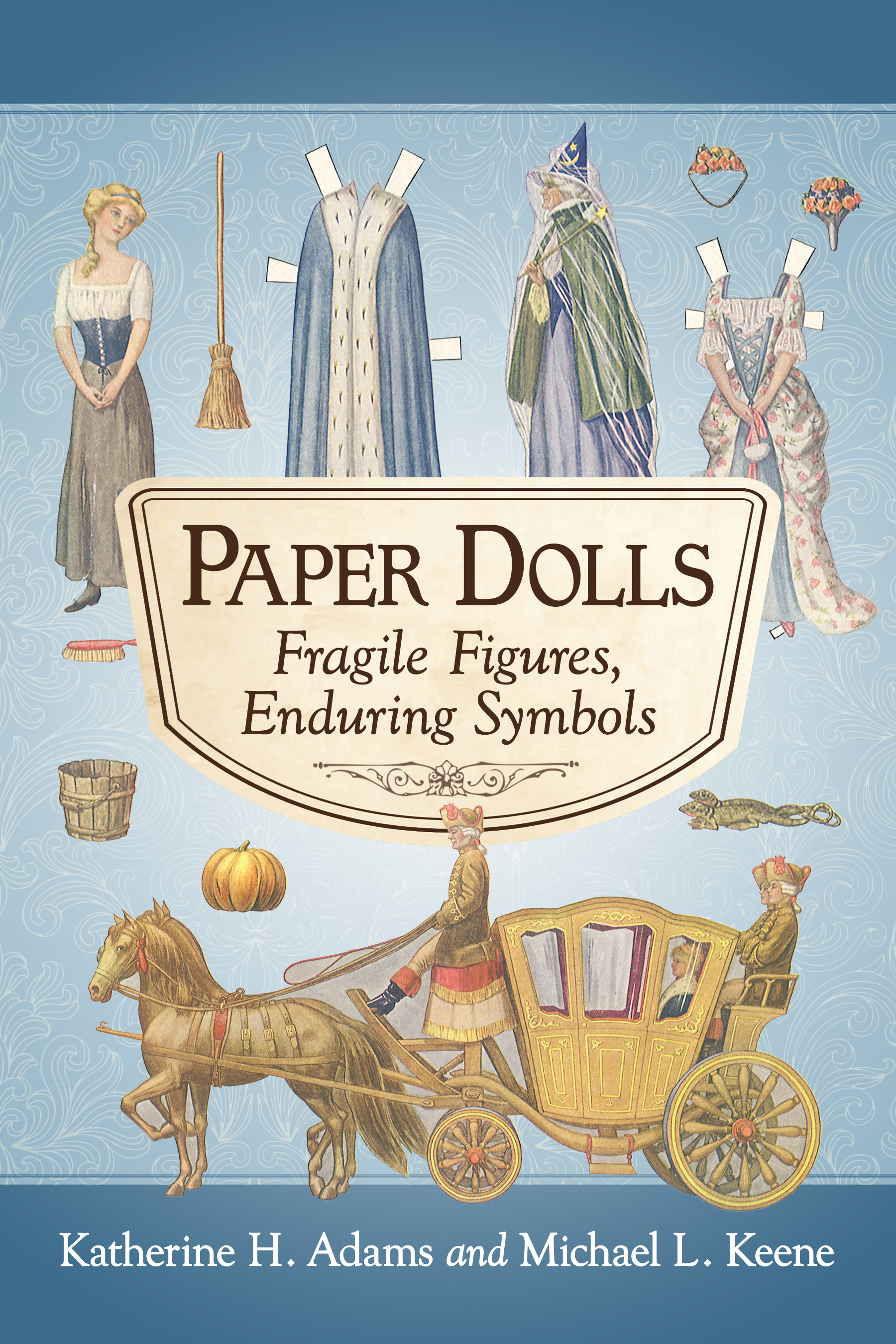

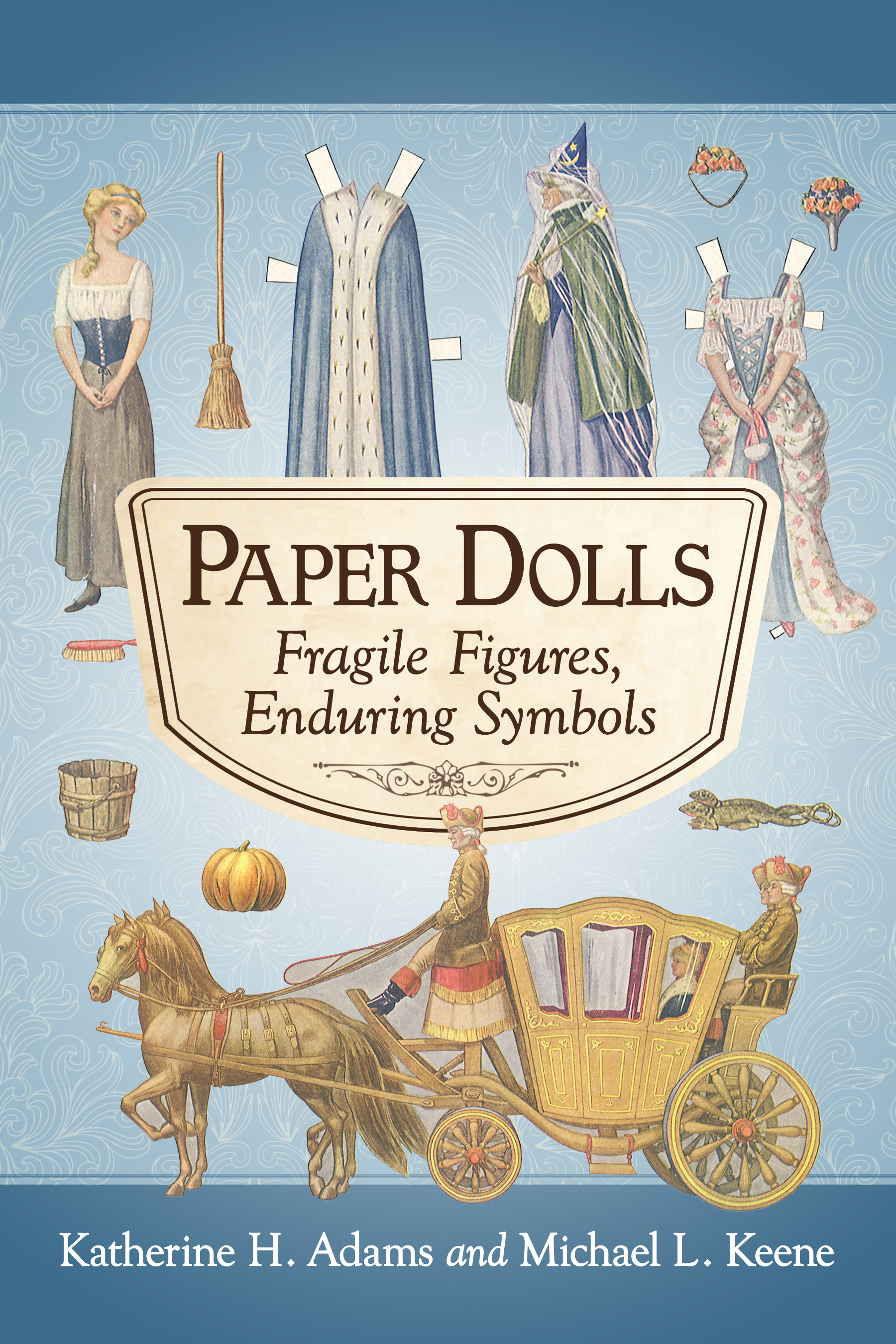

Paper Dolls

Fragile Figures, Enduring Symbols

Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2939-1

2017 Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover image of 1920 Cinderella paper dolls 2017 PicturesNow

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

KHA: For Barbara Ewell

MLK: For all my family

Acknowledgments

As always when we write, we would like to thank the fine librarians of Loyola University, especially Pat Doran and Jim Hobbs.

Kate would additionally like to thank her chair, John Biguenet, and her dean, Maria Calzada, for their kindness and their support. She also profited from insights about the project provided by her departments ELF writing group chaired by Hillary Eklund; by her colleague Laura Murphy; and by Jane Joyner and the Camp Street Readers.

Books came for this project from many libraries through interlibrary loan. We also profited from the research assistance of Mary Borgo at Indiana University.

For the excellent images, we are indebted to the Photoshop skills and generosity of Willie Wax.

Introduction

The longest chain of paper dolls recorded by the Guinness Book of World Records, created in Hendersonville, Tennessee, in August 2014, measures over 25,000 feet, or almost five miles. A British group, led by mixed media artist Paula MacGregor and a non-profit community organization, Slack Space, is now attempting to break that record with dolls made from a template and colored by volunteers. To reach that goal, MacGregor has set up creation stations at community centers, schools, libraries, shopping centers, and fairs. Both through her website and these booths, she is attempting to involve adults and children and thus increase participation in the community, her plan being to join all the dolls by their arms and hands as a symbol of unity.

The paper doll can be read as creating a continuum not just of joined arms and hands but of meaning, throughout history. Certainly over the generations paper has had a great impact as the conveyor of writing and as the medium for the paintings housed in museums. But other sorts of more ephemeral paper images of human beings, wielded as actual item and as symbol by people of all ages and classes, have also had a huge influence, in organizing lives and conveying meaning, their power changing to do the work of different cultures and eras.

Paper dolls, often referred to as paper figures or idols when not expressly intended for children, are two-dimensional figures drawn or printed on paper for which accompanying clothing may also be made.

Paper Dolls through History

Paper dolls have a long history of conveying meaning. Papercutting to create images became common in China with the invention of paper in the first century CE, as a means of crafting religious messages.

The paper figure would quite differently become the jumping jackor pantinin France beginning during the reign of Louis XV. This articulated figure provided amusement to adults as well as a means of critiquing the aristocracy, political satire made possible through a seemingly harmless toy. In various forms, paper figures would endure as a means of satirizing politicians, including, recently in the United States, Sarah Palin, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump.

In the early nineteenth century in England and in the United States, along with continuing to impact politics and social values, paper dolls appeared in stories for children, the emphasis on clothing indicating the transformations possible, especially through active education. As deployed in toy theatres, paper dolls also involved their owners in the extremes of exotic characters and crises.

As paper dolls came into the United States, their accompanying stories would soon be shortened, often appearing just on the envelope in which the dolls were sold. A deluge of products by McLoughlin Brothers and other companies, involving scores of appropriate, affluent outfits, would provide a powerful ongoing vision of American values, depicting the accepted as well as the outsider or Other. Even with no written text, or perhaps especially without one, these dolls, clothes, and accessories would tell an influential (white, middle-class) American story.

Into this century, when fewer children play with traditional paper dolls, their symbolic power has continued apace. In plays, films, and an amazing quantity of novels, both in the teen and adult markets, these figures have continued to serve a complex function, depicting what might be required, of good teenagers for example, as well as the spirited rejection of traditional expectations. And in recent decades, as demonstrated by exhibits and books, many artists have embraced the paper figure to work out their own responses to the current era of paper-thin security and permanence.

What Work They Do

Through the centuries, paper images have concerned religion, politics, and moral codes; the heights of creativity; cultural definitions of womanhood, motherhood, and the family; the proper approach to education; the dictates of fashion; self-image and self-esteem; even the end of life. In developing all of these topics, in many iterations, these figures have always concerned change. As Dominique Buisson mentions, Paper reigns supreme in the subtle game of transformation.

One English paper doll set that sold well in the United States had a title emphasizing dramatic difference: The Protean Figure and Metamorphic Costumes (1811).

These and so many other figures, employed from papers origins in China forward, have portrayed the quick transformations of human life, its ephemeral nature, these images made not just by courtiers or publishers or a few highly trained artists, but across communities, by adults and children, an ongoing presence in material culture. Social critic Gerry Canavan wrote recently that Today anything could happenimmortality is invented, the aliens finally show up, the comet is spotted that will kill us alland we would believe it. We are bathing in change, marinating in it, maybe drowning in it. And one means that people have always employed to respond to change, and at times to direct it, has been the paper figure.

Chapter 1

Paper Power Begins

Paper dolls have a history of symbolism, witchcraft and sorcery, critic Suzanne Aker has claimed, and indeed they do, having been made not only to entertain children but to create religious and social meaning, with a focus on metamorphosis. From the beginning of paper production, in China and Japan, paper figures have protected the home, shepherded the dead, separated good from evil, and taught the young. This vulnerable medium, certainly more fragile than stone or marble, has provided a unique means of considering the thousand natural shocks that the flesh is heir to, the changes of a moment, of a lifetime, or of history. Many of the earliest of figure types have remained powerful, as the actual also became a symbol that could shape the messages of novels, plays, films, television shows, and video games.

Next page