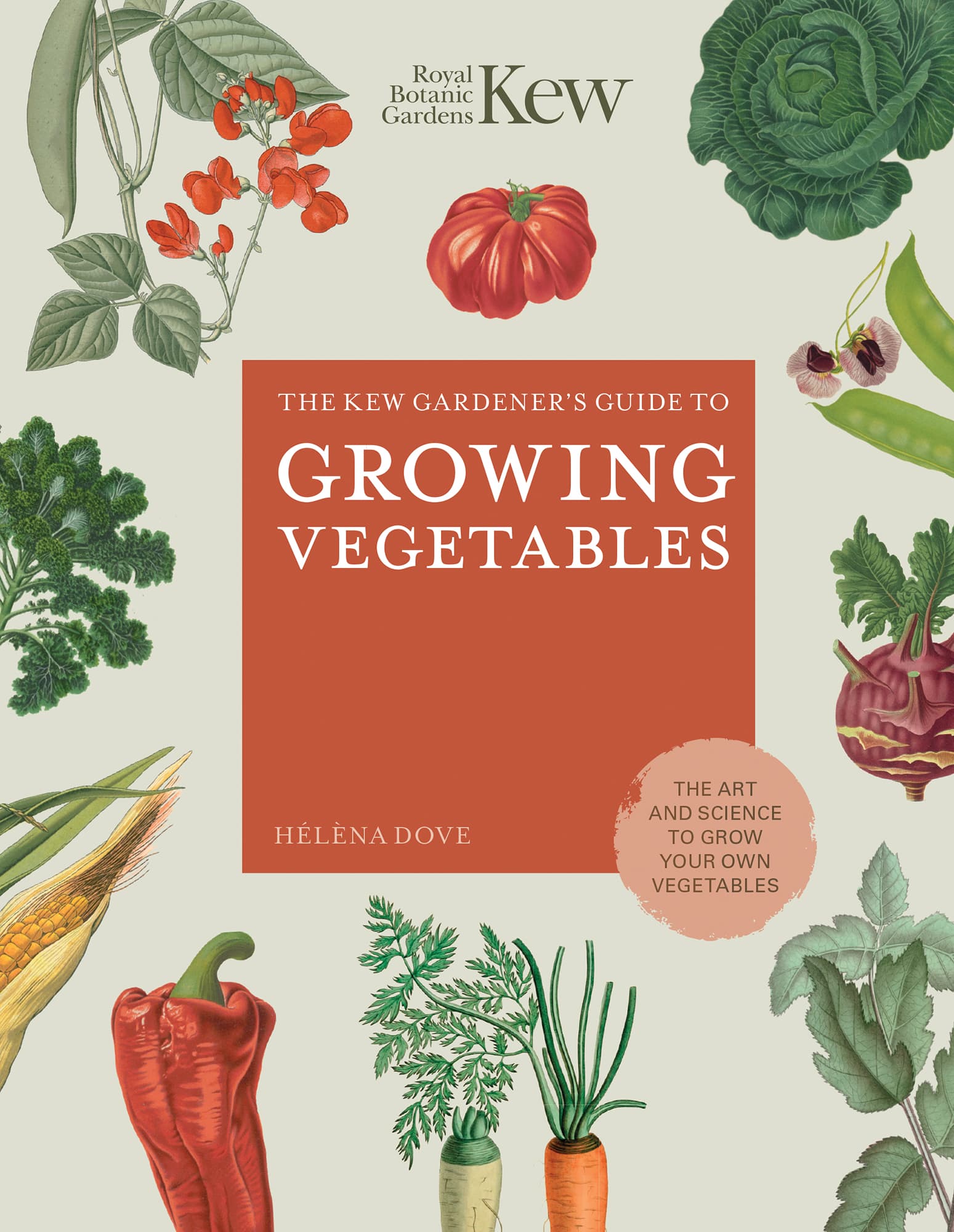

THE VALUE OF VEGETABLES

For many people, growing food is more than just a pastime it is an obsession and a way of life. As well as an engaging hobby, growing the ingredients for your kitchen has many other benefits, too.

When raising food from seed or a young plant, choice can be made over cultivation techniques, and for many gardeners this will include not using chemicals and instead raising vegetables organically. Chemicals are commonly used in commercial food growing to deal with pests and diseases, and to produce the most perfect harvest possible. These chemicals effect the environment around us, and residues inevitably end up on the plate. The home grower can use techniques that do not include chemicals to combat pests and diseases (see ).

By walking into the back garden or cycling to the allotment you can also benefit the environment by reducing the air miles that so much other food travels. Much of the food in supermarkets is flown in from around the world or is transported in trucks from different parts of the country.

The use of fuel and packaging is detrimental to the environment, and to the food itself. Once vegetables are harvested, they start to lose nutrients, sweetness and taste all culminating in the view that locally grown, fresh harvests are best.

Certain crops do not easily survive transportation, even if from a local producer. Crops such as chard tend to wilt and, although completely edible, do not look appetizing by the time they end up in the shops. Other crops are often not available as they do not sell to a wide range of people or may not look perfect to the consumer. Heritage vegetables often fall into this category because they may look slightly unusual: for example, the cracked-skinned beetroot Rouge Crapaudine (nicknamed toad beetroot). They may also be non-uniform, often expensive to crop (as they are not high-yielding) or suffer from diseases. However, heritage crops often provide different tastes or textures: for example, the heritage tomato Ananas, introduced in 1894, has a delicious pineapple flavour.

As well as heritage crops, growing your own vegetables means you can try out crops that have previously been unsuited to your local climate, making these vegetables either non-existent or very scarce to buy. Oca (Oxalis tuberosa) is an Andean crop with a delicious lemony root and is currently being bred to produce marketable harvests, but one plant at home gives enough to try out this interesting ingredient.

Freshly harvested vegetables also encourage more home-cooked dishes and inevitably a good diet with plenty of fresh produce, while the physical action of creating and tending a vegetable garden gives gentle and fulfilling exercise. Gardening has been proven to help lift mood and there is a considerable satisfaction in being outdoors, reaping the rewards of what was sown.

Taking a summer harvest including radish, peppers, courgettes and lettuce directly from plot to plate is a pure delight.

WHAT WE CAN GROW AND WHERE

Understanding your growing space is key to a successful vegetable garden, and getting the most from the plot. Before even putting a seed into the ground, observe the space: where does the sun fall and at what time of day; what type of soil do you have; what is growing well already? The answers to these questions will indicate what crops will thrive.

Hardiness

Researching the hardiness zone your vegetable garden lies in will give an indication of which plants will grow well there. All plants are given a hardiness rating by a governing body such as the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) in the UK. As a rough guide, plants with a rating of H12 are frost tender and will not survive freezing conditions: H3 plants are half hardy and tolerate some cold; H47 plants will live through cold spells, with H4 plants surviving 10C/14F to 5C/23F, and H7 plants living through temperatures colder than 20C/4F.

One way to grow plants that may not thrive in cold conditions is to provide a protected growing area such as a greenhouse or a cloched area. Being able to provide artificial heat to the protected cropping space will again extend the range of vegetables that can be grown, as well as prolong the season of harvest.

When growing vegetables, it is worth noting that some do not like extremely hot temperatures: for example, plants in the brassica family prefer temperatures a little cooler than crops such as tomatoes, so either grow these cooler crops in spring and autumn or provide light shade where possible. Alternatively, use bolt-resistant cultivars such as pak choi Glacier, which withstand high temperatures.

Microclimates

Each growing area will have its own microclimate, which is affected by the lay of the land and hard landscaping. It will influence where crops are planted and what will thrive overall. Researching the equivalent sea level of the garden will give a general feeling for what plants will thrive in the growing area. The higher above sea level the plot is, the cooler and more exposed it is likely to be. Exposed sites will suffer from the wind, which can be detrimental to crops, cause leaf damage and make it difficult for pollinators to fly from plant to plant to pollinate them. The topography of the plot should be noted; if it is on a slope, the aspect of the garden will be accentuated, and the drainage will need improving at the top and possibly also at the bottom.

Once the forced rhubarb is harvested, allow the remaining stems to grow in the light.

In more exposed sites you will be able to grow coastal plants well, such as seakale and cabbage, but you may want to create shelters using hedges or hard landscaping to provide sheltered spots for more tender plants such as tomatoes.

The aspect of the garden relates to where the sun falls. In the northern hemisphere, if the garden faces south, it will be warm and have light for much of the day. North-facing gardens are shadier and cooler, suiting leafy crops.

Forcing

One way of extending a season of harvest is by forcing vegetables such as rhubarb, seakale and chicory. This process works by covering the crop in complete darkness and providing some extra heat, either by bringing them indoors or by surrounding them with a warming material such as bubble wrap, horticultural fleece or manure. Providing these conditions forces the plant to use energy reserves to grow and search for the light, which gives faster growth and leads to a sweeter crop. These crops are often available several weeks earlier than their non-forced counterparts. See also .