Copyright 2017 by David Ortiz

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-81461-5

Cover design by Brian Moore

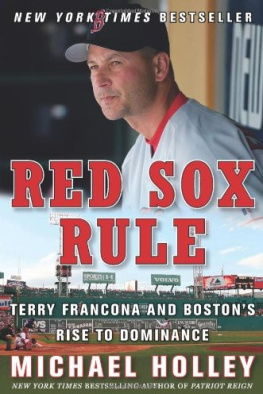

Cover photographs Michael Ivins/Boston Red Sox/Getty Images

e ISBN 978-0-544-81454-7

v1.0417

To Red Sox fans, my second family. Playing for and winning with you is one of the biggest thrills of my life.

David Ortiz

For my lifelong advocates, Michelle and Aryl. Im proud to be your brother.

Michael Holley

Introduction

For many reasons, the statistics say that I shouldnt be here.

I think about that all the time, even when Im lounging on a beach with a nice drink in my hand. The thoughts carry me away, and I alternate between daydreams and remembrances of things that I was spared from. This was a time long before I was celebrated for baseball milestones and home runs in the bottom of the 9th, 10th, or even 12th inning. It was many years before I cursed terrorists and spoke up for freedom without fear. It was before I split my days between trying to win games for the Boston Red Sox and trying to save my sinking marriage, for the sake of my family. Yes, it was even before I became known by a nickname, Big Papi, that resonates throughout Boston, Santo Domingo, and anywhere in the baseball world.

The statistics then had nothing to do with my output as a designated hitter. No one, outside of my family, would have guessed that I would one day redefine the position and accumulate more home runs, hits, runs scored, and runs batted in than any DH in history. But to get there, celebrated and cheered by millions, I had to survive a neighborhood that didnt attract adoring crowds and the bright lights of television.

I grew up in Haina in the Dominican Republic. The city itself was recently cited as one of the most polluted places in the world. There was a battery recycling plant headquartered there, and as a result, battery acid and lead would seep into the soil. Piles of batteries, some as high as three-story buildings, could be found in the city. That alone put lives in danger. Then there was my neighborhood, which I made it out of by grace. My parents, Enrique and Angela, were strict on my younger sister, Albania, and me. They had to be. Our lives depended on it. We were poor, and our neighborhood was teeming with violence and crime. Shootings. Stabbings. Drugs. Gangs.

The statistics say I shouldnt be here.

My parents tried everything they could to protect us from our surroundings while we lived there, all the while hustling to make enough money so we could get out. Our house was small, with the main rooms divided by walls no thicker than plywood. That small house was large enough to have patches of land in the front and back, our yards, and the backyard was the only place where Albania and I could play in the neighborhood. The fear, from my mom and dad, was that wed get caught in some crossfire that had nothing to do with us.

There are a few things from growing up that stay with me now, seared into my memories forever. I remember my parents sitting Albania and me down and showing us a bag. It had what appeared to be a white, powdery substance in it. I can still remember the stern looks on their faces, their eyes making contact with ours and locking there for the entire, brief warning.

You will probably see this. Someone might ask you to take this. Dont do it.

The bag contained a type of cocaine that had been circulating through the neighborhood. My parents were concerned enough to physically show it to us so we would know exactly what to avoid. They also firmly delivered a message that I still share with young people today: drugs can be around you, and someone can offer you drugs... but there is nothing that says you have to take them. Nothing. Ultimately, you control the situation.

Some things were beyond controlling, beyond the shield and shelter of my parents. Once, my mother sent me to the bodega to pick up some groceries. On my way there, I saw a guy murdered. Right in front of my eyes, killed. I saw things that no one should see, especially a kid.

I saw it, yet never became it, thanks to God and my parents. To this day, Im a ghetto boy who made it out, but where I came from still is in me. I dont let people see it, especially in the corporate circles Im in now. Yet I never forget. If I ever do, thatll be the day that I lose my humility, so Im glad to remember.

Im glad that my three children have never had to live under the physical and financial pressures that I did as a kid. But in retrospect, my upbringing equipped me for every success and challenge Ive ever had in baseball. Every single one. Watching my parents in that environment taught me about discipline, hard work, and being a provider, even amid the worst circumstances. Id always laugh inside when I heard people talk about producing in the clutch in baseball. Please. That was nothing. I can tell you that I never felt pressure, not one time, strolling to the plate in a baseball game. I knew I wasnt going to get shot playing baseball. I knew that something I did could lead to a celebration, and I like to celebrate.

As adventurous as my life in baseball was over the course of twenty years, it was still a life in baseball. There were rules in place. Guidelines. In baseball, there were certain things that always could happen, or never could happen. My life, my real life, wasnt like that. And that unpredictability led to several life-changing events.

On the first day of 2002, I received news so devastating that I thought my heart would never fully recover. And Im still not sure that it has. I learned how much sports can hurt people in 2003 and, in 2004, how they can help heal people too. I saw the goodness and beauty of an entire organization, singing together, in 2007. I had my character, my very essence, questioned and mocked in 2009. The next year I was urged to give up baseball and go home. Three years later, in 2013, I was the MVP of the World Series. In 2016, in the final regular-season game of my career, I looked to heaven for the spirit of my mother. My father was standing by my side. The president of the Dominican Republic was there. And on the field, cameras roamed and flashed, prepared to share my story with millions of people.

But that was just a small part of it. It all began in Haina, fighting against violence in the air and on the ground. Thats where I, Enrique and Angelas son, learned to survive. They taught me how to work. The journey that followed taught me how to persevere and yet be transformed.

I find it amazing, and ironic, that a life beyond anything Ive ever imagined has been made possible by playing baseball. I say that because baseball isnt even the sport I wanted to play.

Who didnt want to be like Mike in the late 1980s and early 1990s? I was a kid, and I played and thought about basketball constantly. My friends and I would go neighborhood to neighborhood, trying to find basketball games. I remember playing a tournament in Santa Rosa, about a 90-minute drive from my home in Haina. We knew all the NBA stars: Michael Jordan, Karl Malone, Magic Johnson, Charles Barkley, Larry Bird. I was big for my age, six feet tall when I was 10 and six-four at 14, and I was a power forward. Man, I was athletic, and I could run and jump. I thought it was the most beautiful game, exciting and entertaining, and thats what I wanted to do.

My father Enrique always had different plans. He was happy that I was interested in sports at all, since that made it less likely Id be drawn into the chaotic environment of our neighborhoodpeople caught up in gangs, shootings and murders, people lost to drugs, in a big way. My country, unfortunately, became known as a Caribbean bridge for drug trafficking between the United States, South America, and Europe. There were billions of dollars in international drug transactions, which led to some dark, depressing, and corrupt tales in the Dominican. It had a devastating effect on the culture then, and its still a huge problem now.

Next page