PENGUIN  CLASSICS

CLASSICS

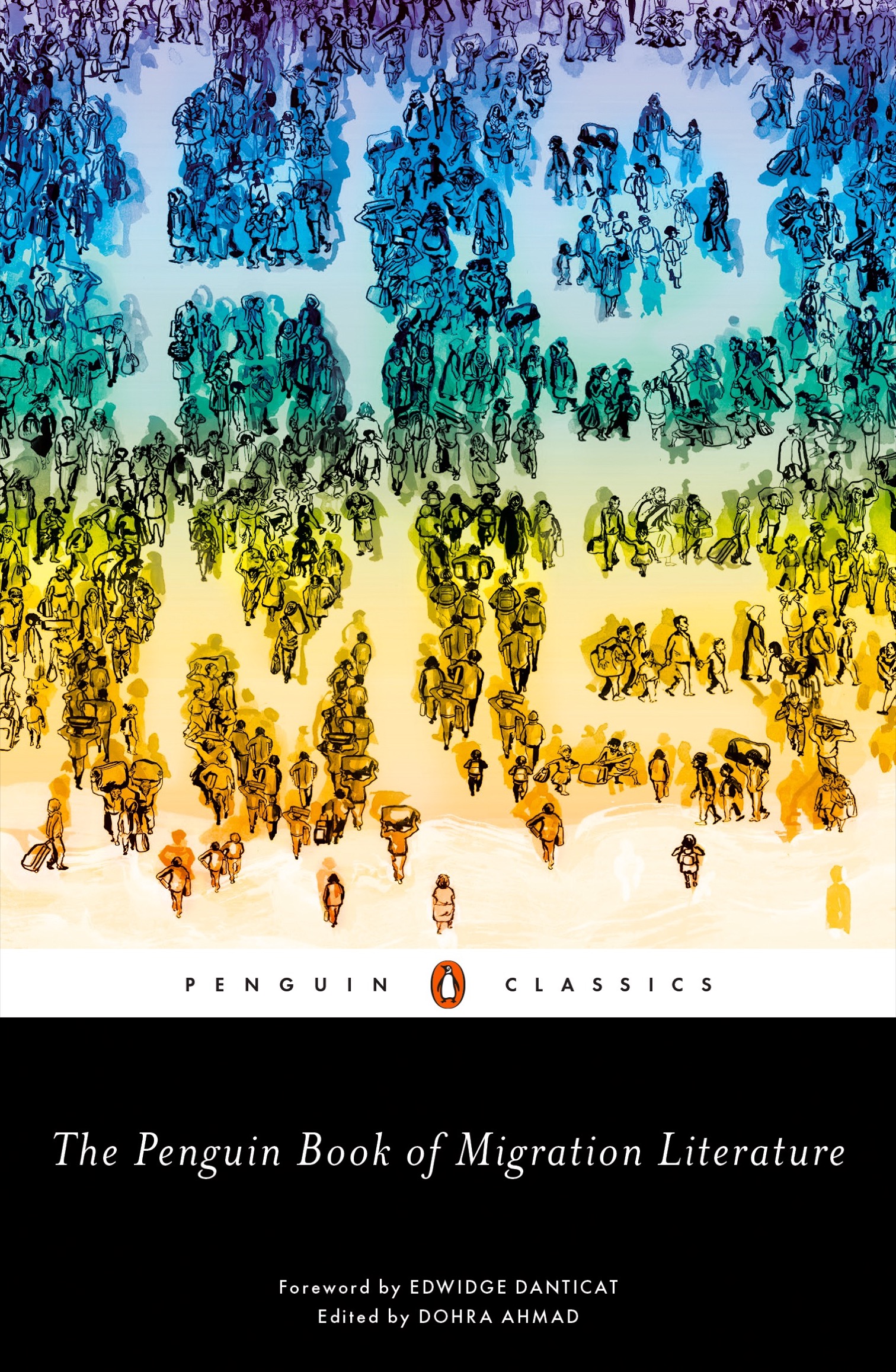

THE PENGUIN BOOK OF MIGRATION LITERATURE

DOHRA AHMAD is professor of English at St. Johns University. She is the author of Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America, editor of Rotten English: A Literary Anthology, and coauthor (with Shondel Nero) of Vernaculars in the Classroom: Paradoxes, Pedagogy, Possibilities. Ahmad also contributed an introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of The Housing Lark by Trinidadian author Sam Selvon. Born in Chicago, she has lived in Amsterdam, Lahore, and San Francisco, and now lives in Brooklyn with her family.

EDWIDGE DANTICAT is the author of numerous books, including Everything Inside; The Art of Death, a National Book Critics Circle finalist; Claire of the Sea Light, a New York Times Notable Book; Brother, Im Dying, a National Book Critics Circle Award winner and National Book Award finalist; The Dew Breaker, a PEN/Faulkner Award finalist and winner of the inaugural Story Prize; The Farming of Bones, an American Book Award winner; Breath, Eyes, Memory, an Oprahs Book Club selection; and Krik? Krak!, also a National Book Award finalist. A 2018 Neustadt International Prize for Literature winner and the recipient of a MacArthur Genius grant, Danticat has been published in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Harpers Magazine, and elsewhere.

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Published in Penguin Books 2019

Introduction and selection copyright 2019 by Dohra Ahmad

Foreword copyright 2019 by Edwidge Danticat

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

A portion of the foreword by Edwidge Danticat was published in different form in We Must Not Forget Detained Migrant Children in The New Yorker, June 26, 2018.

constitute an extension of this copyright page.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Ahmad, Dohra, editor, author of introduction. | Danticat, Edwidge, author of foreword.

Title: The Penguin book of migration literature : departures, arrivals, generations, returns / edited with an introduction by Dohra Ahmad ; foreword by Edwidge Danticat.

Description: New York : Penguin Books, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019004724 (print) | LCCN 2019010719 (ebook) | ISBN 9780143133384 (pbk.) | ISBN 9780525505167 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Emigration and immigration in literature. | Immigrants in literature. | Exiles in literature.

Classification: LCC PN56.E59 (ebook) | LCC PN56.E59 P47 2019 (print) | DDC 808.8/03552dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019004724

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Cover illustration by Matt Huynh

Version_1

For migrants everywhere

Contents

THE PENGUIN BOOK OF MIGRATION LITERATURE

no one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark

WARSAN SHIRE , HOME

And, hungry for the old, familiar ways, I turned aside and bowed my head and wept.

CLAUDE McKAY , THE TROPICS IN NEW YORK

defining myself my own way any way many many ways

TATO LAVIERA , AMERCAN

Foreword

One of my earliest childhood memories is of being torn away from my mother. I was four years old and she was leaving Haiti for the United States to join my father, whod emigrated two years earlier, to escape both a dictatorship and poverty. My mother was entrusting my younger brother and me to the care of my uncle and his wife, who would look after us until our parents could establish permanent residencythey had both traveled on tourist visasin the United States.

On the day my mother left, I wrapped my arms around her legs before she headed for the plane. She leaned down and tearfully unballed my fists so that my uncle could peel me off her. As my brother dropped to the floor, bawling, my mother hurried away, her tear-soaked face buried in her hands. She couldnt bear to look back.

Even the type of carefully planned separation that my parents chose tore their hearts out. Whenever they were eating, my mother used to say, they wondered whether my brother and I were eating, too. When they went to bed at night, they wondered if my brother and I were sleeping. Even though we spoke to them on a scheduled call once a week, they never stopped worrying and longing for us.

It is perhaps that ache and longing that made my parents take me to visit Haitian refugees and asylum seekers who were being held at a detention center near the Brooklyn Navy Yard when our family was reunited in New York, in the early 1980s. I have continued to visit detention facilities over the years, including ones where children are held, either alone or with their parents. At a childrens facility in Cutler Bay, Florida, most of the boys and girls had been detained for so long that theyd transitioned from childhood to adolescence behind those walls. Then there were the Miami hotels turned detention centers, where women and children were being held for weeks or months at a time. Up to six women spent twenty-four hours a day in one room, often with crying babies and toddlers, while armed guards patrolled the halls.

One of the most distressing aspects of migration, for both adults and children, is how invisible the migrant can become, even when being detained, or imprisoned, in our proverbial backyards. When vulnerable populations are kept hidden, or are forced into hidingwhich is the daily reality of so many undocumented migrants, immigrants, and refugeesthey not only live in the shadows; they become slowly erased and their voices become muffled or go unheard.

Thats why its so illuminating to have a book like this at this particular time, an indispensable anthology full of intimate and deeply moving poems, short stories, novels, and memoirs about what its like to live on the margins of borders today. This book dares to ask what departures, arrivals, and returns are like, what being in motion means at a time when, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 68.5 million of our fellow human beings are coming and going because of war or economic, environmental, or political instability.

The Penguin Book of Migration Literature: Departures, Arrivals, Generations, Returns also explores what home is and can become. Is home the place where we are born, where, as we say in Haiti, our umbilical cords are buried? Or is home the place we die, where we are buried? Or is home the place where we toil in between? The place to which weve sacrificed our youth, our strength, the place to which we have given the best years of our lives? Some of us are born speaking one language and will die speaking another. We are seeds in one soil and weeds in another.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS