Introduction

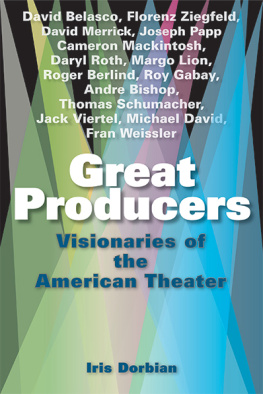

More than twenty-three years ago, I signed a contract with producer Joseph Papp to work on a definitive oral history of the New York Shakespeare Festival/Public Theater, the most significant not-for-profit theater group in the country. Over the course of the next eighteen months, I interviewed more than one hundred and sixty people and turned nearly ten thousand pages of transcript into a roughly eleven-hundred-page manuscript. I considered it then, and still consider it today, the most significant and compelling work Ive done in more than forty years of journalism. The story of why something with so much to recommend it would take so many years to appear is in some ways as dramatic and surprising as the book itself.

I came to this project because Joe Papp, in search of a collaborator, came to my agent, Kathy Robbins. Though theater was not my main passion, Kathy thought of me because, despite decades of difference in age, Joe and I shared a common background as first-generation Americans, both raised in Brooklyn by Yiddish-speaking immigrant parents.

Also, I had a feeling for collaboration and voice: in the years before and since, Ive worked on books involving Patty Duke, Carol Matthau, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Sid Caesar, and Ava Gardner. More than that, as a journalist I knew that Joes story was among the most significant of contemporary cultural narratives, a critical piece of American theatrical history, and I wanted to be part of telling it.

In his years with the Shakespeare Festival and the parallel Public Theater, Joe had made theater in America both accessible and essential. Hed produced landmark plays like Hair, A Chorus Line, That Championship Season, The Normal Heart, and Short Eyes, plays that people had to pay attention to because they transcended their moment in time.

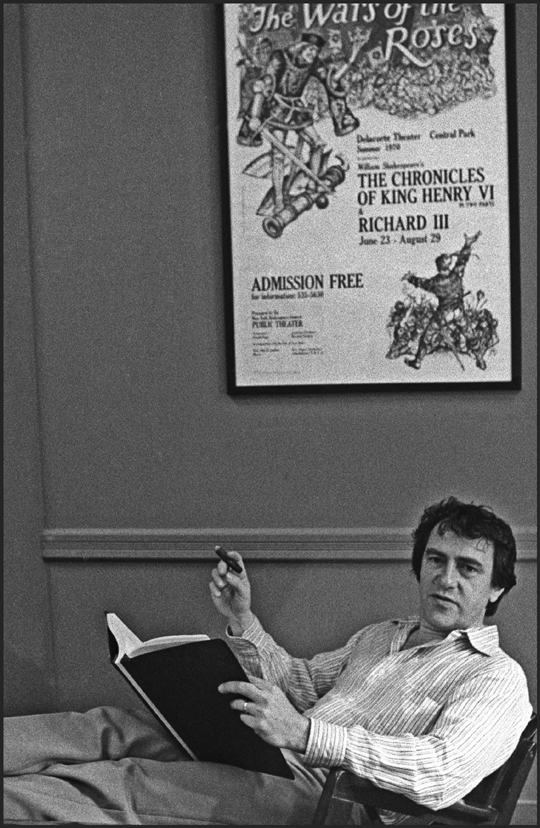

Papp had been essential in starting the careers of actors like George C. Scott, Meryl Streep, Raul Julia, Kevin Kline, James Earl Jones, and Martin Sheen. Hed had towering disputes with everyone, from New York Citys all-powerful bureaucrat Robert Moses to the very playwrights and actors he hired, but almost everyone ended up doing their best work for him. When he died the New York Times, noting the more than 350 plays hed brought to the stage, called him one of the most influential producers in the history of the American theater. He was larger than life just by being himself.

A story like this, filled with alive, articulate not to mention theatrical people, turned out to be especially suited to the oral-history format. There is a vividness and immediacy about direct speech, a sense of life about individuals speaking for themselves, that makes oral history the most intrinsically dramatic of narrative mediums. The people interviewed were, almost without exception, wonderful talkers and tellers of tales.

The weaving together of these various strands created a kaleidoscopic tapestry of memory that made a virtue of what sounds like a potential liability: every participant has their own story, their own truth, and everyone remembers the same situation in slightly different ways. But this Rashmon effect also means that when you put all these stories together, minor discrepancies fade and the joined voices provide a sense of the texture of reality, of what actually happened, which nothing else can. In a similar fashion, even though the severity of the illnesses that killed them prevented me from talking to Michael Bennett (A Chorus Line) and Miguel Piero (Short Eyes), conversations with friends and collaborators brought them to life in a very real way.

Though New York is the center of the Shakespeare Festivals universethe place, for instance, where Joes right hand, Bernard Gersten, patiently led me through the twists and turns of his almost lifelong connection with the maninterviewing for the book led me across the country.

I have strong memories of listening to Tommy Lee Jones calmly dissecting what went wrong with True West while he meticulously brushed down a horse at his remote California ranch. I remember taking the train to Connecticut to spend long hours with David Rabe, and still appreciate the time and care he took to be thorough and thoughtful about his enormously complicated dealings with Joe, a relationship that was the most significant and intensely emotional of any the festival produced. And I am unlikely to forget flying to Scranton to interview Jason Miller, who took me straight from the airport to a raucous social club that seemed right out of That Championship Season. When I tentatively commented on the resemblance he grinned, shot me a look from his dark, intense eyes, and said, Are you kidding? This is the play!

Wherever they were, these people knew what a good story was and how to put it across. To hear Colleen Dewhurst talk about acting with George C. Scott for the first time; to hear Scott himself describe the Richard III that made his career (and tops my list of productions I wish Id seen); to listen to Roscoe Lee Browne tell how Leontyne Price helped advise him about a career in acting; to discover that Bob Fosse, of all people, had been a shipmate and collaborator of Joes during World War II; to hear how The Pirates of Penzance came together and how that benighted True West fell apartthis is to be present at the creation of theatrical history.

And then there was Joe himself, who both disliked taking time to talk about the past when he could be working on some future project and recognized his obligation to do so. The veteran, as he well knew, of innumerable battles and clashes of will (If I were estranged from all the people I had arguments with, he told playwright Lawrence Kornfeld, Id have nobody to talk to), he was reticent about nothing hed been through, no matter how upsetting the memory, once he sat down to talk.

The only exception to that were stories about the difficult poverty of his childhood, which, along with the youthful radicalism it led to, was critical in informing the decisions he made, the kind of institution he was determined to build. After a Saturday-afternoon session in his Greenwich Village apartment talking about that painful period, Joe walked me to the door, looked at me, and said quietly, Im never talking about that again. He didnt just mean to me, he meant to anyone.

Working with Joe on a project of this scope, talking to all the people hed written notes to asking for collaboration, was enormously exciting, but from time to time I also feared that, as had happened with others hed worked closely with, a rift would develop between us. And once he read the manuscript, that is what happened, with a vengeance. Disturbed and troubled, Joe refused to allow the book to be published.

Even at this remove, I dont feel completely sure about how the factors involved in that decision combined in Joes mind. In part, he was upset by some of the things the people hed fallen out with said about him, but the reality is that what Id handed in was an overlong and likely repetitive first draft, and with the usual tightening and fine-tuning that go into the editing process, much of that material would as a matter of course have not made it into the final draft.