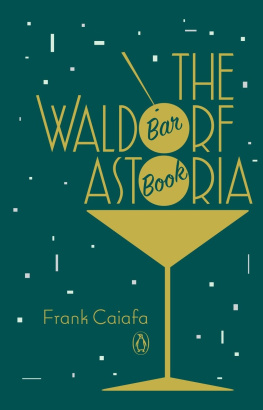

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

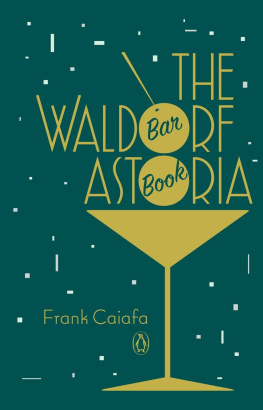

The Old Waldorf-Astoria Bar Book by Albert Stevens Crockett published by Dodd, Mead and Company 1934 This revised and expanded edition published in Penguin Books 2016

Copyright 2016 by AB Stable LLC DBA Waldorf Astoria New York

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Illustrations by Josie Portillo

ISBN 9780698136069

Cover design: Matteo Bologna

Version_1

C ONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I drink to the general joy o the whole table.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

I n the summer of 2005, I responded to an advertisement for a bar manager position. No mention was made of the venue, but when I made the short list, I discovered the restaurant was the newly renovated Peacock Alley, in the lobby of the Waldorf-Astoria. The opportunity to manage this iconic venue with such a long and storied history and many of New York Citys brightest culinary stars was one I couldnt pass up. At the time, there werent many beverage programs in NYC (or anywhere, for that matter, and certainly not in hotels) that concentrated on classic and seasonal cocktails along with a well-curated wine-by-the-glass program, prepared with care and meant to pair with the restaurants cuisine. Though it had begun a few years prior in small bars and speakeasies, todays cocktail renaissance was really just getting under way, as the now classic NYC bars where we have come to expect this brand of service from were just opening.

Peacock Alley was an ideal showcase for ideas that had not fit the menu at my previous bars. I ran toward the challenge not only to offer such items but to execute them consistently and in an extremely high-volume arena. No easy task. After all, it would be the first time in its history that Peacock Alley would have a proper bar in the dining room and lounge. Previous incarnations did feature cocktail service, however drinks were prepared at a service bar to the side of what was then known as the Peacock Alley Caf and Lounge or in the back of the house at a service bar far from the guests views and then delivered to the dining room floor. Finally the lobby patrons of one of the most celebrated hotels in the world could congregate, imbibe, and see and be seen from a perch worthy of its history. More than thirty feet long, set in the center of the main lobby, this would represent the new beginning and the return of a proper bar worthy of its Fifth Avenue predecessor, which served its last historic drink at the onset of Prohibition. The new Peacock Alley would coexist with two iconic bars in the Bull and Bear Prime Steakhouse and Sir Harrys Bar. We would be players on an unparalleled stage. With an eye toward the future but fully aware of its storied past, we set out to accentuate the classic aesthetics of the Old Bar.

I grew up in a New York City much different from the one that exists today. When it came to bars in the 1970s and 80s, for instance, their open room-temperature vermouth bottles were a year old and spoiled. Further, a good portion of the fine folks who had been paying their rent working pridefully as bartenders probably couldnt tell you much more than that their Scotch was from Scotland and their beer from Milwaukee.

Today, vermouth has returned to its rightful place in the cocktail pecking order with varied choices, which include small-production brands and limited releases from larger houses. The skilled and well-trained bartenders behind the stick today not only can identify from where each whiskey hails but can probably describe the method of distillation and the master distiller to boot. Its a different world.

I recall going to the old Jimmy Days Bar on West Fourth Street when I was sixteen or seventeen years old, having what I thought was the best pea soup in the world with a beer, hoping no one would card me. I watched as the older gentleman behind the bar, with his slightly soiled apron, muddled an orange wheel, a neon red cherry, and a spoonful of sugar in a double rocks glass (I dont recall the use of bitters, but I will give him the benefit of the doubt), pack it tightly with chipped ice, and glug in as much blended whiskey (usually Fleischmanns or Seagrams) as the glass could hold. Toss another cherry on top and a squirt of club soda from the soda gun and there was your Old Fashioned. Nearly every nonalcoholic item was dispensed from the soda gun, including overly sweetened and artificial sour mix and sometimes even juice. Today, the use of a soda gun is not a sign of the coming apocalypse. Artisanal soda producers are creating cane-based syrups that can be used in that system. Even the old soda gun has evolved.

Those were not discerning times. Women frequently ordered Madrases (vodka, cranberry juice, and orange juice) and Melon Balls (vodka, Midori melon liqueur, and pineapple juice). Even the simple, fresh, and sometimes maligned Cosmopolitan (citrus vodka, triple sec, fresh lime juice, and a touch of cranberry) was still a few years away. Most men were drinking whiskey neat or in Highballs and mass-produced domestic beer, without any artisanal bitters in sight.

A catalyst for change was Americas resurgent interest in all things culinary and the publics concern over what they served on their tables at home. Particularly here in New York, people went out for lunch and dinner, and beginning around the early 1980s or so it became the norm to identify a chef with his restaurant. Chefs became brands unto themselves. Word of mouth and unsolicited buzz began an interest in a component of the business previously reserved for the toniest of establishments. That begat the resurgence of television chefs, who really had not had a presence in the American home since the days of Julia Child and the Galloping Gourmet. It was inevitable that this kitchen culture (which never really went out of style in other countries) would turn its attention to the beverage portion of the meal. As palates were educated, people with increasingly selective tastes and expanding food vocabularies desired more from their predinner cocktail, choice of wine with dinner, and digestif.

Yet, as I stress with the team, not everyone wants an artisanal vermouth or a dissertation on the differences between Speyside and Islay Scotch whisky. Nor do they want a pre-Prohibition-style Old Fashioned, and yes, some people simply want a vodka tonic or a cold beer. It is really all about our guests. Our job is to provide them with what they want without a look down our collective noses. We are here to put smiles on peoples faces and help create memories. If we procure that smile from an archival cocktail that was served in the Old Bar a hundred years ago, or from the finest Bay Breeze this particular guest has ever had, it doesnt matter in the least. To me, especially today, when everyones time is at a premium, the more welcoming we can make our guests experience, the better off everyone will be.