About the Authors

Helen and William Bynum have had a lifelong interest in plants and gardening and are making a two-acre garden in Suffolk. Helen Bynum studied at University College London and the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine before lecturing in medical history at the University of Liverpool. She is now a freelance lecturer, editor and writer. She is the author of Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis (2012), co-editor with William Bynum of Dictionary of Medical Biography (2007) and Great Discoveries in Medicine (2011), and co-editor of the Biographies of Disease series.

William Bynum received his MD from Yale University and his PhD from the University of Cambridge. A Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London, he is professor emeritus of the history of medicine at University College London. His numerous books include The History of Medicine: A Very Short Introduction (2008), A Little History of Science (2013) and, as editor, Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine (1993; with Roy Porter) and The Oxford Dictionary of Scientific Quotations (2005).

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to our editor Colin Ridler at Thames & Hudson and to Gina Fullerlove Head of Publishing at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, for sharing our excitement and taking this book forward. Kew has very fine human resources as well as the most wonderful collections of art and literature devoted to plants. Julia Buckley from the Illustrations Team of the Library, Art and Archives at Kew insisted that it was a team effort, but her patient, unflagging and enthusiastic help has been invaluable. Thanks to Dr Shirley Sherwood, Brigid Edwards and the estate of the late Mary Grierson for allowing us to use images.

All the Kew Library reading room staff coped with our huge request lists with a smile and provided a smooth, efficient and conversant service. UCL and Suffolk Libraries also helped made this book possible. The immensely knowledgeable Mark Nesbitt, Curator of the Economic Botany Collection, Kew, kindly read the entire text and made wonderfully piquant comments for which we are very grateful. Additional help at Kew came from Christine Beard, Anna Trias Blasi, Lorna Cahill, Paul Little, Trishya Long, Barbara Lowry, Christopher Mills, Lynn Parker, Martyn Rix, Kiri Ross-Jones, Georgina Smith, Maria Vorontsova, Paul Wilkin and Lydia White. Dorian Q. Fuller and Michael D. Coe made helpful comments on parts of the text. Lin Zhang helped with Chinese poetry and translations. Any errors that remain are our own.

At Thames & Hudson Niki Medlikovas and Lauren Necatis design skills are evident, and thanks also to Sarah Vernon-Hunt and Rachel Heley.

Andy and Nancy Scull have an amazing garden in San Diego and took us to Muir Woods; Sarah Duignan asks the right kind of pointed questions and Emma Kelly just gets it. Thanks to all.

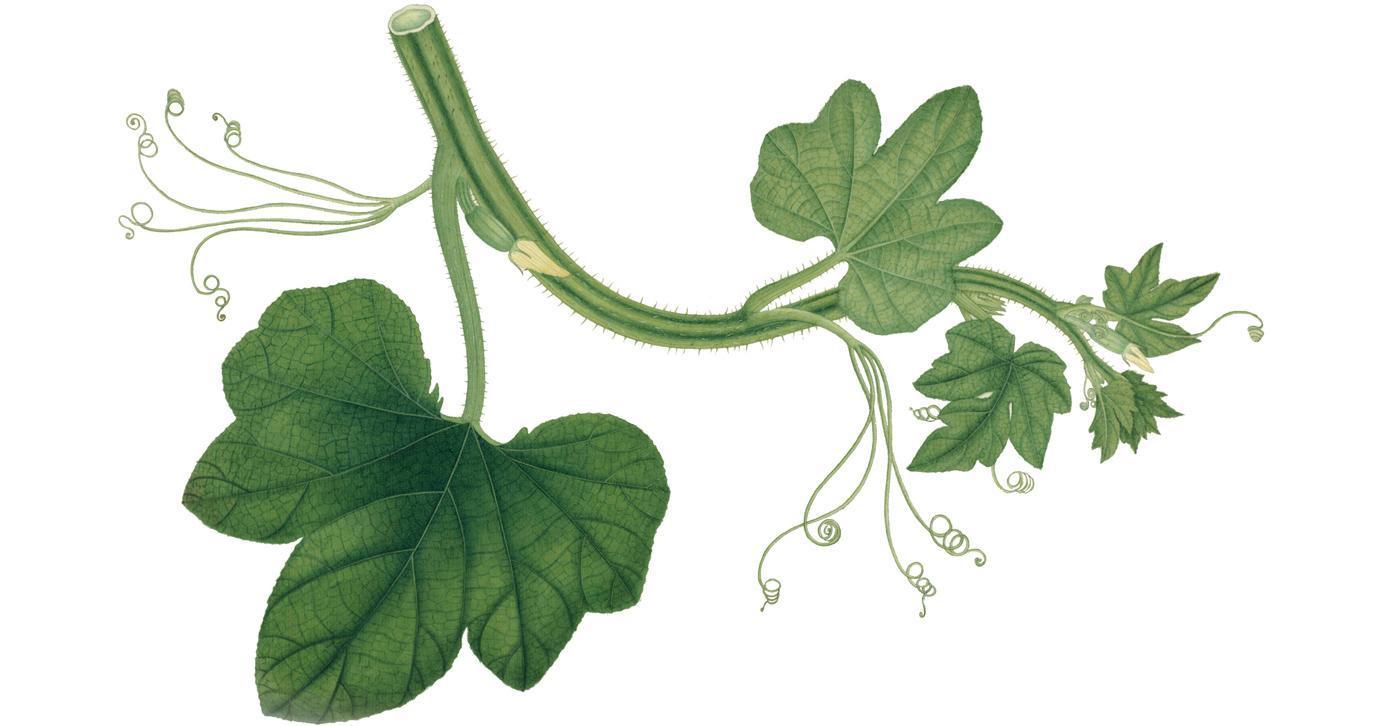

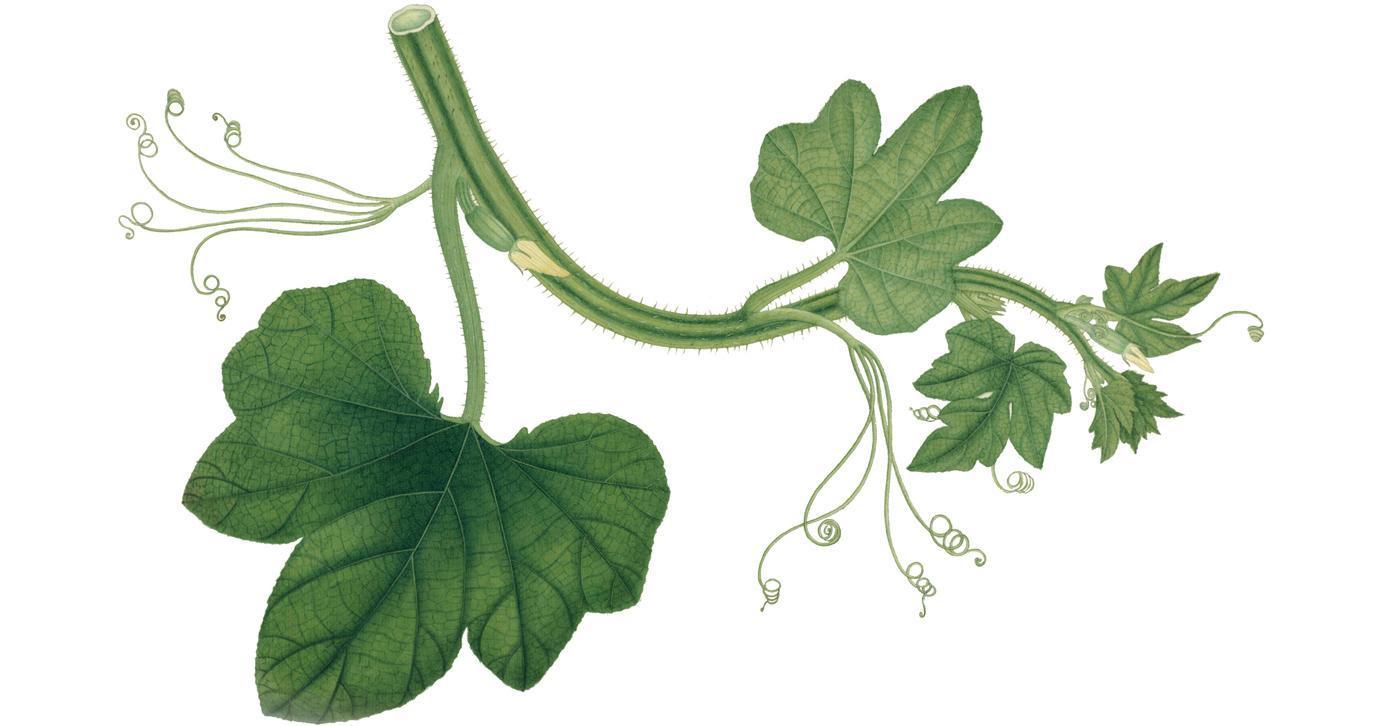

Tendrils, young leaves and flower buds of squash (Cucurbita pepo) all can be consumed and were eaten before the fruits were bred to increase the flesh around the nutritious seeds.

The shift from foraging to farming as the Earth warmed after the last ice age is one of the great transitions of human history. It was a protracted and by no means inevitable trajectory. The early farmers were often less well nourished than their foraging predecessors and subject to a disease burden resulting from close contact with humans and animals intentional or otherwise. It is, though, from the permanence enshrined in farming that most of our present-day cultures have evolved.

Only in the continent of Australia did farming not take hold among the original inhabitants. In Asia, Europe, the Americas and Oceania it occurred independently, and involved different groups of plants the founder crops grains, legumes, tubers; exactly what depended on where. Lentils, potatoes, yams, breadfruit, along with many others, formed the basis of diets around the world. Technology and seeds were then also carried from one place to another. Additional plants fruits, vegetables, herbs were brought into the garden. To the potent images made by humans as hunter-gatherers were added the art and artifacts representing a settled way of life. Storage, processing and cooking provided a new impetus to practical material culture. Deities believed to watch over the annual planting of seed and the subsequent harvest were feted and feared; life moved to new rhythms.

Farmers gradually altered the landscape, clearing and preparing land for growing crops and herding animals. Crucially, they also transformed the plants they came to rely upon. Under cultivation these plants were domesticated so that they came to vary in fundamental ways from their wild ancestors.

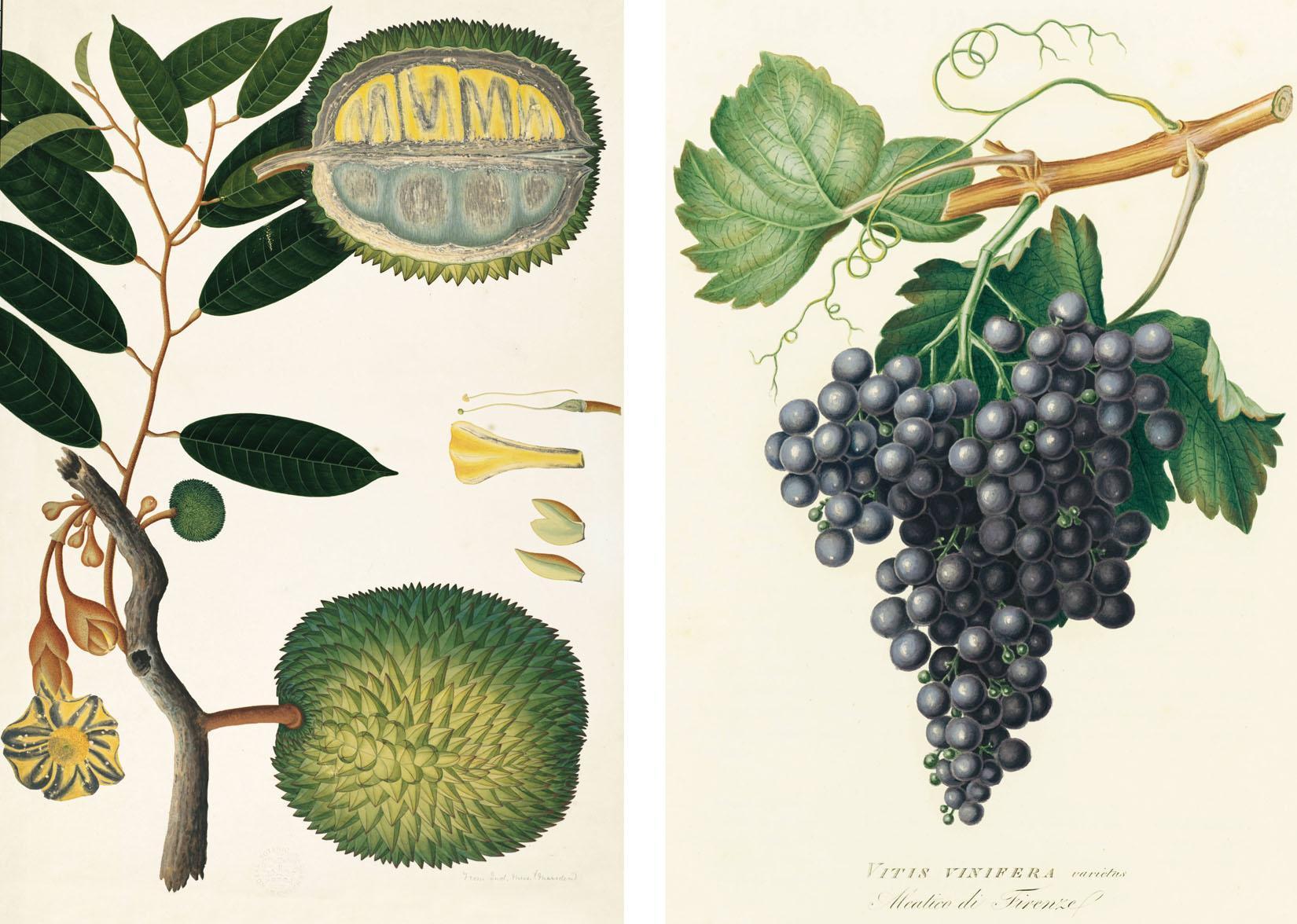

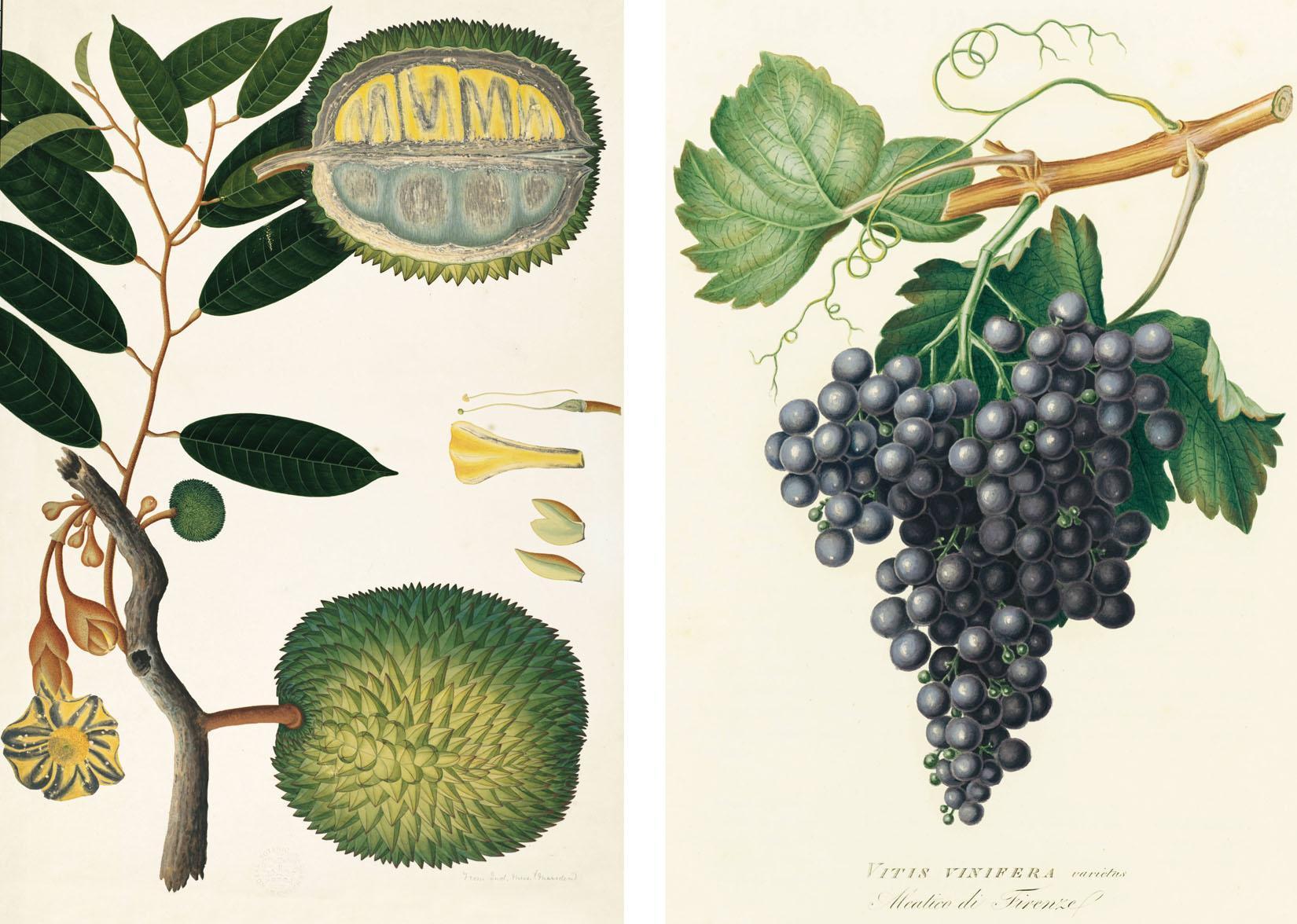

Left A relative of the breadfruit of Oceania, the jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) is thought to have originated in Indias Western Ghats and is used as a vegetable and fruit, even substituting for rice. It is an important food source in the subcontinent, especially for the poor, and is also attracting attention for increased utilization in the tropics.

Right Aleatico di Firenze grapes (Vitis vinifera). Aleatico grapes were known as a specific variety from at least the 14th century. Vines growing on Elba are used to make rich Muscat-like dessert wines, enjoyed by Napoleon Bonaparte during his exile on the island.

Take the cereals. Archaeology has revealed that we gathered the seeds of many of these wild grasses such as wheat, rice and maize before we deliberately planted them. From purposeful cultivation of wild plants, early farmers went on to select those that had randomly mutated and better suited their needs. It was much more efficient to cut the stems of wheat or rice with intact ears and thresh them to release the grains than pick up what had been shed on the ground. A different genetic shift that resulted in seeds all germinating on the same environmental cue spring rain or warm sunshine was another great advantage over the wild state. Cereal growers also chose to plant seed of more flavoursome and plumper-grained parents that stood on thicker stalks, the better to hold up newly enlarged heads.

Seemingly ordinary, the founder crops of grains and pulses, roots and tubers were the transformers of our race around the globe. To their starch and protein are added here the fruit and oil of the olive and the flesh and juice of the grape, the elements, along with wheat, of the Mediterranean triad. They remind us that early farming encompassed a breadth of diet and technique. All represented a commitment to the land and an enduring sense of purpose. Farming was here to stay.

Triticum spp., Hordeum vulgare, Lens culinaris, Pisum sativum

Ceres, most bounteous lady, thy rich leas

Of wheat, rye, barley, fetches, oats and pease.

William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act 4, Scene 1

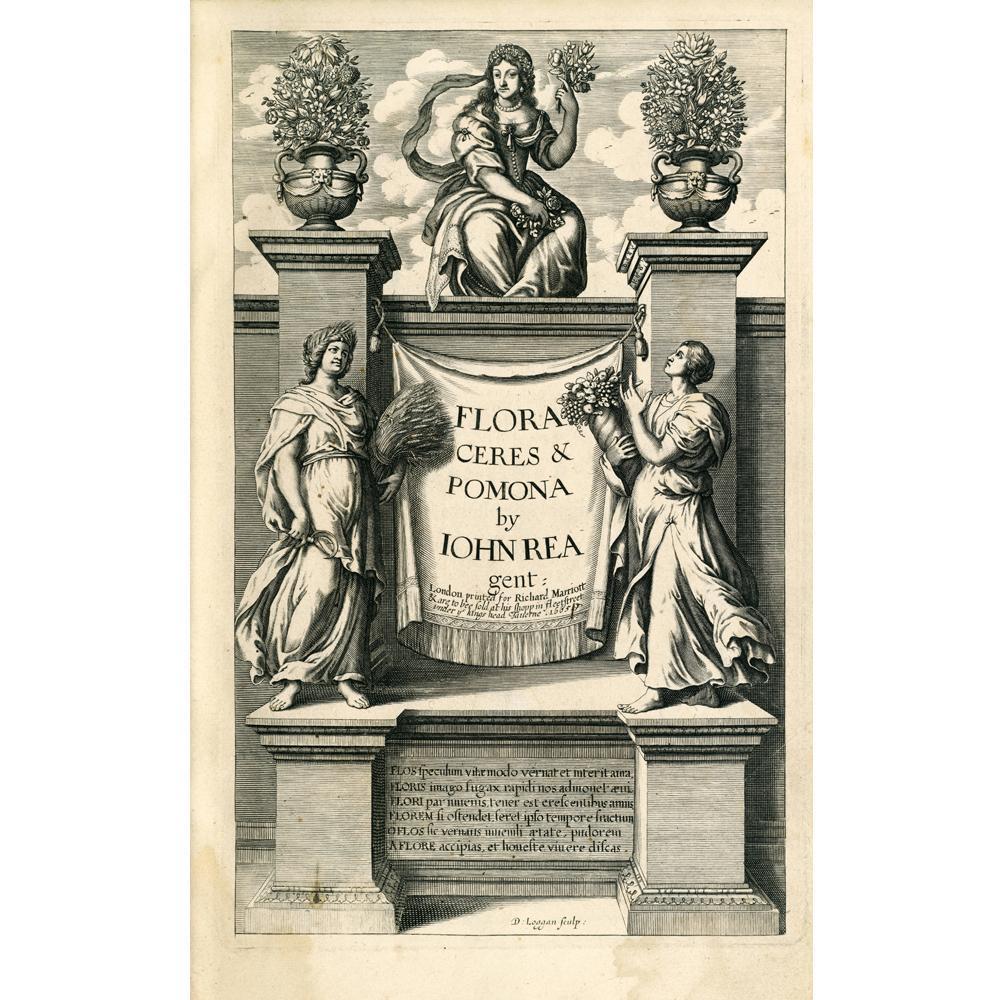

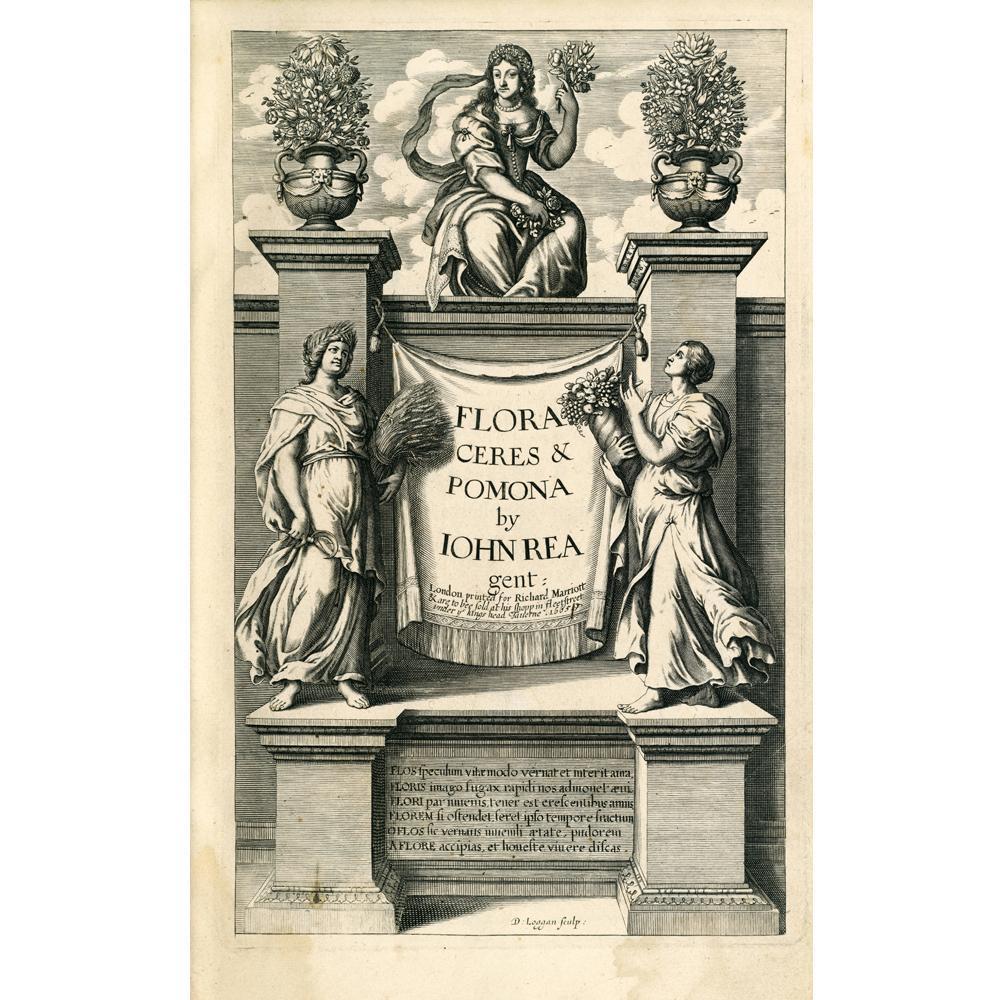

Flora, Ceres and Pomona, the Roman goddesses of flowers, grains and fruit, form the frontispiece to John Reas A Complete Florilege (1665). Rea (d. 1667) was a nurseryman and garden designer, renowned for his tulips.

Wheat and barley, lentils and peas; these are the quintessential grains and pulses of the Neolithic revolution in Southwest Asia. They are some of the most important foods that allowed us to adapt our way of life in the face of the changing climate and plant landscape around 11,500 years ago at the beginning of the Holocene. Rather than being the brilliant inventors of a settled agricultural economy, we need to see our ancestors as coping as best they could by relying upon a small number of key crops when circumstances dictated and survival demanded.

Next page