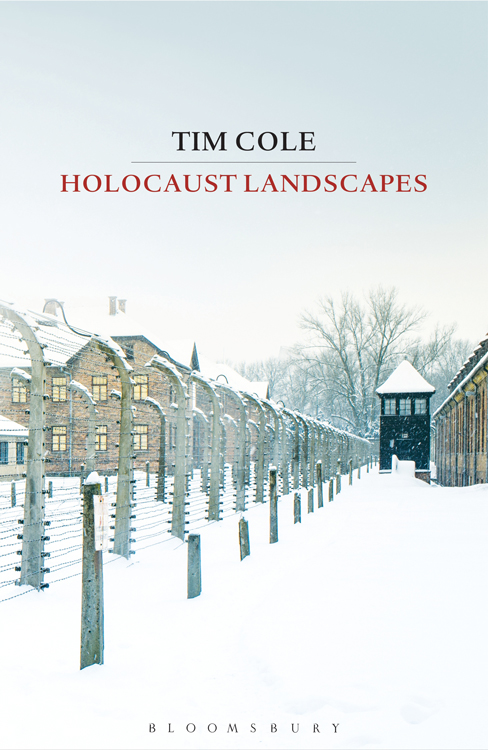

HOLOCAUST

LANDSCAPES

TIM COLE

For Jonathan, Jeremy and Matthew

Joseph Elman recalled his father Benjamin drawing a rough sketch map to convey to his sons the hopelessness of their plight crammed into the ghetto set up in Proushinna after the Nazi occupation of eastern Poland in 1941. Safety, in his fathers eyes, lay in a place. But the place he had in mind was one of the few countries during the Second World War that remained neutral, and such places were all achingly distant. Boys, look, here is Poland, Joseph recalled his father telling them:

and then he drew, you know, you got Czechoslovakia, he knew exactly all... Europe. He says, You havent got a single country, neutral country. You got Sweden and Switzerland... even if youll get out the ghetto, he says, you got such a long way to go and youre going to be caught.

Reflecting back on this conversation, Joseph wondered:

I dont know to say if he was right or not right, who knows? I mean that geographically he was... right, because... if you have a border, you could... get out. But he didnt realize, you know... we did know there is some woods, partisans, we dont have to go. Now, if we wouldnt have the woods near, you know, itd be a problem... from Warsaw... from d, where they going to go?

For both Joseph and his father, where they were mattered enormously in all sorts of ways. At its most basic level, they were in the wrong place at the Originally divided between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in 1939 under the terms of the MolotovRibbentrop non-aggression pact, eastern Poland was later occupied in the summer of 1941 as the launch of Operation Barbarossa saw the rapid eastward expansion of Nazi Germany deep into the heart of Soviet territory. Jews were caught up in this euphoric moment of German military success. Some were placed in rapidly constructed urban ghettos and work camps. Others were killed in waves of shooting, oftentimes in the forest on the edge of town. It was here in eastern Poland and the Soviet Union in the second half of 1941 that the so-called solution of the Jewish question turned murderous.

But this was an event that never stayed still. Genocide was on the move, starting in the east but then heading westwards over the course of the war, and as it moved it changed shape. What began as genocide in the neighbourhood turned into killings and labour exchange on a continental scale before shifting to the more intimate, personal shootings of Jews on the banks of the Danube in Budapest or the roadsides of Germany. Eventually, the tragic story culminated in men, women and children being transported to overcrowded camps such as Bergen-Belsen that are perhaps best seen as post-genocidal space. Instead of viewing the Holocaust as a single, monolithic event, rather different genocides were enacted in different places, at different times across the course of the war. Moving through these landscapes, I have been struck by how focusing on place highlights the shifting chronology of the genocide. Rather than geographies of the Holocaust being ahistorical, my sense is that probing ideas of place and space, as I do in this book, foregrounds histories as much as geographies of the Holocaust.

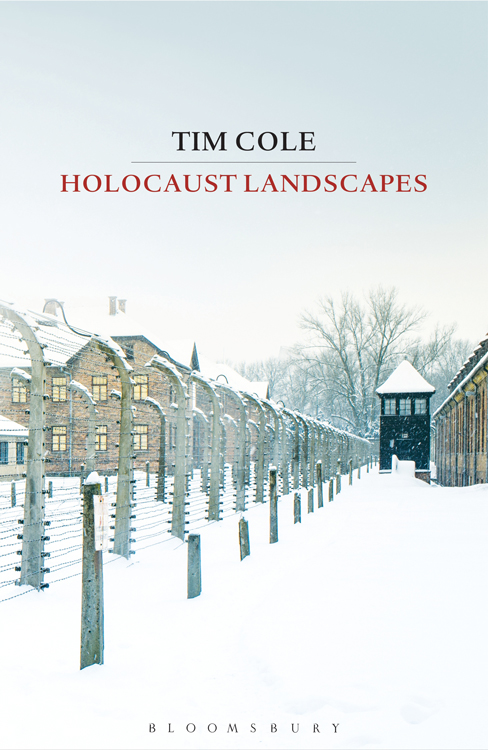

But the Holocaust was not simply something that happened at particular times and in particular places. It was also a place-making event that created new places ghettos and camps within the European landscape, or reworked more familiar places such as rivers or roads into genocidal landscapes. It was in one of these novel places the ghetto built in Proushinna that Josephs father, Benjamin, delivered his geography lesson to his sons. Their family was, in a sense, fortunate to remain living in their family home, although this home was now repositioned within the city in a ghetto that physically separated Jews from non-Jews. Over the course of 1942, the ghetto population swelled as Jews who had survived the waves of killings in the local area were brought into Proushinna. Ultimately the ghetto was liquidated, its population transported to the most infamous of places associated with the Holocaust: the complex of camps at Auschwitz.

Neither Joseph nor his father ended up in Auschwitz. Josephs father, along with other members of the Jewish Council who assumed leadership roles in the ghetto, committed suicide prior to its liquidation. Joseph, and a group that had made contact with the partisans in the neighbouring woods, escaped from the ghetto and survived the war living in the forest. There they dug bunkers into the soil, which was another act of Holocaust place-making. Holocaust landscapes were not simply sites of incarceration and killing, but also of escape and hiding. While the Holocaust involved the construction of thousands of sites of incarceration by Nazi Germany and her collaborators, it also involved the construction of thousands of hiding places where Jews and non-Jews sought to carve out spaces beyond German control. Although the Holocaust involved the forced transfer of millions within and across national borders, it also meant that hundreds of thousands decided to flee within, and outside of, occupied territory.

For Josephs father safety was a place, a neutral country, too distant to imagine ever reaching. However, for Joseph, safety lay much closer to home in the woods that surrounded Proushinna. There was a generational divide among Jews in how sites of safety were imagined. Although both father and son were in agreement that safety lay in a place, they differed in what that place was and where it was to be found. For Josephs father, safety lay in the traditional political geography of national sovereignty and therefore could only

While Josephs father saw Europe as divided between the unsafe places of German occupied territory and the safe places of neutral territory, on the ground things were much more complex. Many individuals and families did not adopt the kind of binary that Josephs father worked with, but operated with mental maps that identified more or less safe places at a range of scales from the continental to the local. Even within the most iconic sites of Nazi control the ghetto, camp or column of evacuees on a death march individuals and groups adopted spatial strategies of survival as they tried to go here, rather than there, in a desperate attempt to stay alive. Across the shifting course of the genocide, survival remained profoundly spatial.

Driven by an interest in the range of spatial strategies of survival that individuals, families and groups developed, I have drawn heavily on the stories that survivors have told in diaries, memoirs and oral histories. In doing so, I am conscious that many voices are missing. Whereas we have Joseph Elmans voice, we only hear his fathers voice echoed through his sons retelling. Stories of survival dominate over stories of murder. Like every other scholar of the Holocaust who uses oral history sources, I am aware that we hear almost nothing from those millions who were killed, meaning that in some senses we never really get to the very heart of the matter.

This was brought home to me recently as I guided a group around some of the sites of the former ghettos and camps in Poland just as I was finishing off the last chapters of the book. I took the group to see fragments of the former ghetto wall in Warsaw and Krakw, as well as the barracks at Auschwitz and Majdanek. But I also took them to see the memorial sites at two of the Operation Reinhard camps Treblinka and Belzec. These were sites built solely for murder and operated with a terrible efficiency during 1942 as Polish Jews were killed en masse. Belzec, the first of the Operation Reinhard camps, was a place where Jews from the surrounding regions were gassed shortly after arrival, with only a handful temporarily spared to work in the

Next page