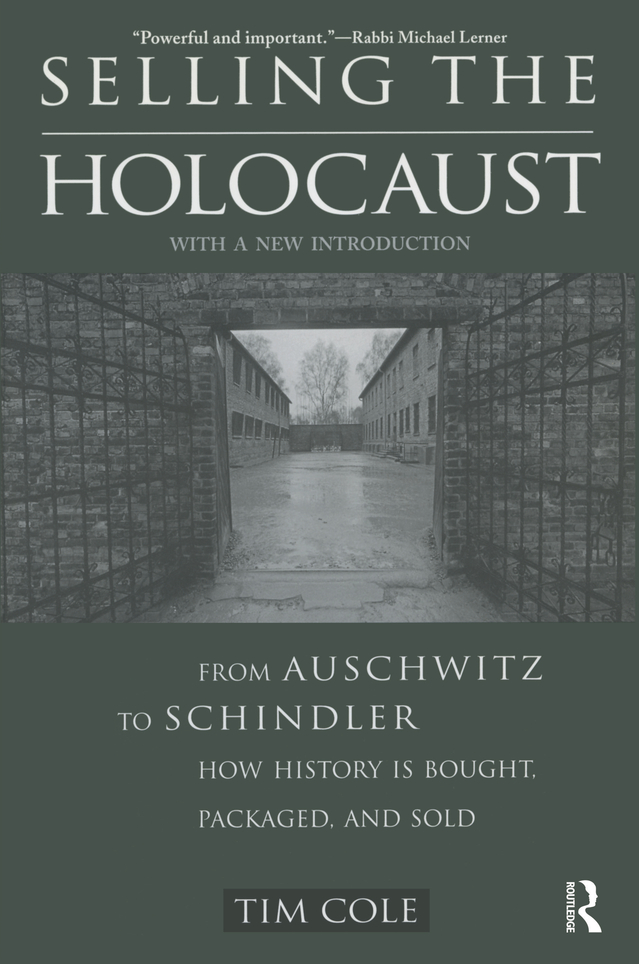

First published in 1999 by

Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd.

Published in 2000 in the United States of America by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue,

New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1999 by Tim Cole

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN0-415-92581-9hb/0-415-92813-3pb

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Typeset by Derek Doyle & Associates, Mold, Flintshire

I first began thinking about how the Holocaust has been represented after what proved to be the jarring experience of visiting Auschwitz in the Spring of 1994. I had gone there on a pilgrimage of sorts, while researching for my PhD thesis on the Hungarian Holocaust. However, what struck me about this place, which I had read about but never visited, was that there were two quite different Auschwitzs for the tourist to visit. That night in my hotel room in Krakw, I read Jonathan Webber's Frank Green Lecture 'The Future of Auschwitz: Some Personal Reflections'. This started me thinking not just about the Holocaust as a historical event, but also how that historical event has been represented in the last fifty or so years. From asking the question 'how', I have increasingly been drawn to ask the question 'why', and in many ways it is those two questions which are central in this book.

This is a book which was in large part taught before it was written. My ideas owe much to the University of Bristol graduate and undergraduate students with whom I have enjoyed discussing how and why the Holocaust has been remembered and represented. The process of putting those ideas into print has been helped along by a large number of individuals. I am thankful to John Vincent for first introducing me to Robin Baird-Smith at Duckworth. It was Robin's initial enthusiasm which prompted me to start writing, and his patient advice and encouragement which have helped bring this book to completion. Also critical in that process has been my editor, Martin Rynja.

Over the last year and a half, I have been struck again and again by how much writing is a cumulative process. I owe a particular debt of gratitude to the many historians and journalists who have reflected on the memorialisation of the Holocaust over the course of the last twenty or so years. In particular, the writings of Omer Bartov, Saul Friedlander, Geoffrey Hartman, Lawrence Langer, Edward Linenthal, Judith Miller, Jacob Neusner, Alvin Rosenfeld, Tom Segev, Jonathan Webber, Isabel Wollaston and James Young have both guided and stimulated my own thinking to a considerable degree. Their influence is to be felt in the following pages, in a book which makes no claims to being either the first or the last word on Holocaust memorialisation. Rather, it builds on what has gone before, and hopefully provokes questions which others will take further.

The collaborative nature of scholarship has also been brought home to me through the support and encouragement of many of my colleagues at the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Bristol. I am particularly thankful for the bibliographical references given to me by Bernard Alford, Tony Antonovics, Robert Bickers, Peter Coates, Kirsty Reid, Hugh Tulloch and John Vincent, and the useful feedback given to me by colleagues when I used some of the material from the chapter on Auschwitz to speak to the half-day conference organised by the department's 'Reputations' research cluster. Reflecting more generally on the theme of 'Reputations' as this research cluster does has stimulated me to think more fully about how and why the 'Holocaust' has gained the kind of reputation it has at the end of the twentieth century. Further afield, our Erasmus link department in Hannover gave some very useful feedback to a seminar paper on Anne Frank, as well as introducing me to Thomas Rahe at Bergen-Belsen, who gave me an insight into some of the questions being asked by someone at the cutting face of 'Holocaust' memorialisation. The University of Bristol has provided me with not only a stimulating environment for both teaching and research, but also with financial support from the Arts Faculty Research Fund and library resources. I am particularly grateful for the efficient help of the staff at the Inter-Library Loans department of the University of Bristol Library whom I have called upon many times since arriving in Bristol.

One of the greatest pleasures in researching this book was enjoying the kind hospitality of friends who provided a bed, meals and conversation as I travelled. I am particularly thankful to Mark, Connie, Annie and Nathan Dever in Washington, DC; Harry and Gladys Evertsen in Houston; David and Alison Boubel in Dallas; and Jon Doye and Sue Bird in Amsterdam. I am also thankful to Jon Doye and Sue Bird for reading and commenting so thoroughly on a final draft of this book. Thanks also to Bob and Pat Evertsen, who spent hours searching for obscure books in San Antonio bookstores, and to Matthew Sleeman and Jeremy Lindsell, who drove down to Bristol to restore my sanity as I came towards the end of writing this book. Their friendship is something which I value.

Above all others, three people deserve special thanks. My parents Roger and Christine Cole first taught me to take an interest in the past and to question everything in both the past and the present. My wife Julie has not only been dragged around more Holocaust museums in the last year than most people visit in their lifetime, but has listened and responded to my initial reactions to those museums. Her comments during the process of writing this book have been insightful, and her critical reading of the final draft extremely useful. She has been a wonderful companion during the last year and a half of writing, and it is therefore to her that this book is dedicated. I hope that she will now allow me to write the next one!

Tim Cole

Bristol

December 1998

This morning on the radio, I heard something I've been expecting to hear for a long time: a Republican congressman from California stated that if Europe had not taken guns away from its citizens, the Jews would not have been defenseless when the Nazis came for them. Invoking the Holocaust to teach a lesson of the dangers of gun control did not exactly surprise me. After all, the Holocaust has been used to lend weight to a remarkable variety of positions. But when I listened to the congressman further, I was struck that he made direct reference to Schindler's List rather than to the Holocaust. His realization came, he recounted, while watching the movie. In a scene where a group of 'Nazis' round up a group of Jews, he noticed that the Nazis were the only ones with guns; hence he realized the importance of the freedom to bear arms.

By referencing Schindler's List, the congressman was invoking what I call the 'myth of the Holocaust' rather than the historical event that has become known as the Holocaust. This 'mythical' celluloid rendition of the event is one that among other things, stresses as I discuss in Jewish passivity. Spielberg did not make a movie about the Warsaw ghetto uprising where a number of Jews were armed, although that ultimately did little to change the fate of Warsaw's Jews but about a group of Polish Jews who are saved through the actions of one (Ger)man. Thus the congressman's lesson comes not from an engagement with the complexity of the Holocaust but from the streamlined simplicity of a Hollywood movie.