Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

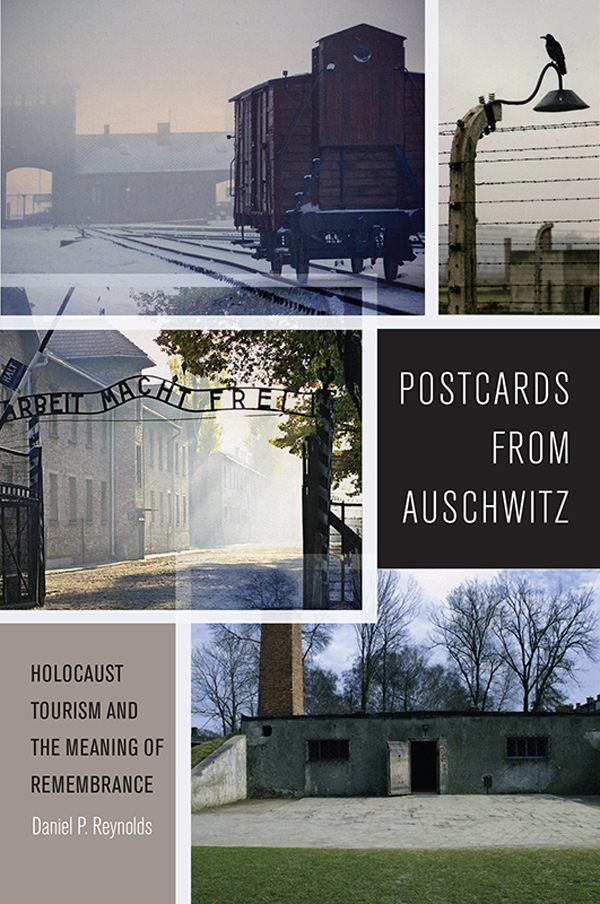

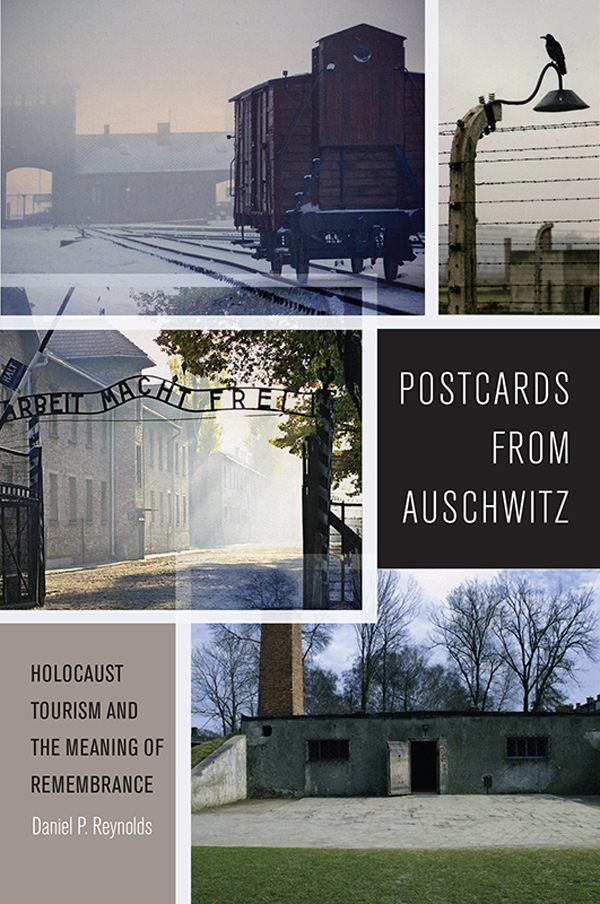

POSTCARDS FROM AUSCHWITZ

Postcards from Auschwitz

Holocaust Tourism and the Meaning of Remembrance

Daniel P. Reynolds

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2018 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Reynolds, Daniel P., author.

Title: Postcards from Auschwitz : Holocaust tourism and the meaning of remembrance / Daniel P. Reynolds.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017038142 | ISBN 9781479860432 (cl : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)Historiography. | Concentration campsEurope. | Holocaust memorials. | Heritage tourismSocial aspects. | Dark tourismSocial aspects. | Collective memory.

Classification: LCC D 804.348 R 49 2018 | DDC 940.53/18dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017038142

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

CONTENTS

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first concentration camp memorial I ever visited was Breendonk, just north of Brussels, Belgium, where my family lived for several years while my father, a U.S. Army officer, was stationed at NATO headquarters. The occasion was a field trip consisting of about fifty high schoolers and was part of our curriculum on World War II. Breendonk, built in 1909, had been a Belgian fort; in 1940 the SS took it over during the Nazi occupation of Belgium. Built entirely of concrete, the camp was remarkably well preservedand perhaps the most frightening, cruelest place I had ever seen. The visit impressed the reality of brutality upon me in a way that exceeded my teenage imaginations efforts to comprehend the Third Reichs mass murders through history textbooks or the recently aired television miniseries, Holocaust . Our tour was led by a former prisoner who stressed quite emphatically that the camp held captive not only Jews (though Jews did constitute half of the camps inmates) but also political prisoners such as himself. I remember being struck by the remark, not only because it departed from my exclusive association of concentration camps with Jewish victims but also, perhaps more important, because I thought I detected resentment toward the Nazis most numerous victims. Whether I understood the guides sentiments correctly or not, it had never occurred to me that victims might not be united in their suffering, and this impression troubled my idealistic assumption that something positive and harmonious could emerge from the calamity of Nazi terror.

Over the last decade, well after my only prior experience of a concentration camp site, I have toured other camp memorials in Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Poland, and France. Yet, at least superficially, the circumstances of these recent tours have not been so different from that of the high school field trip. The thirty intervening years have allowed for deeper preparation, greater agency in my participation, and a richer educational context, but one constant throughout the visits has been a sense of dislocation, experienced as uncertainty about the right way to beor even whether to beat these sites. Is speaking at such places appropriate? Photography? I have felt compelled to consider my relationship to a space deemed sacred and to ask whether tourism is an intrusion of the profane. Often it has been the other tourists who have prompted introspection, either by the way the visit visibly affected them or by the behavior of some I found disruptive: people laughing, posing for pictures, or otherwise showing less deference than I assumed appropriate, leaving me to wonder if or how I should respond. In the end, I have always left these tours with the desire to learn more about what I have seen and even to return. This book is an effort to account for that dynamic of dislocation and increased curiosity in my experiences as a tourist.

I am grateful to many people and agencies for their support of this project and their continued encouragement. The research for this book was supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, whose advocacy for scholarship in many fields outside the sciences is a vital national resource. I would also like to acknowledge Grinnell Colleges sustained support of my research through travel grants and time to complete the work. I am grateful to Jennifer Hammer, Dorothea Halliday, and Amy Klopfenstein at New York University Press for their encouragement and feedback and for ushering the book through the publication process. I have many colleagues at Grinnell College to thank, especially David Cook-Martin, Karla Erickson, and Astrid Henry, who offered their critical acumen and their valuable time to support this work at many stages. I am also grateful to my colleagues Jenny Anger, Todd Armstrong, and David Harrison, who took an interest in the work and who each organized and participated in some of the travels and conversations that shaped it. Valerie Benoist also read portions of the project and offered her helpful insight. Id also like to thank Carolyn Dean, Torben Jorgensen, Thomas Pegelow Kaplan, Desmond Wee, and Stephan Sonnenburg for valuable feedback and opportunities to further develop the research. I thank Konstanty Gebert for enriching my thinking about Polish efforts to remember the Holocaust. Hanna ervinkov and Juliet Golden at the University of Lower Silesia organized an especially valuable trip to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in 2016. I am grateful to Ian Stout and Luc Janssen for their editorial contributions and to my students, both past and present, who have sharpened my thinking about the subject of this book.

Locally, I am grateful to Mark Finkelstein of the Jewish Federation of Greater Des Moines, Rabbi David Kaufmann, Stephen Gaies at the University of Northern Iowas Center for Holocaust and Genocide Education, and Elke Heckner at the University of Iowa for opportunities to share this work.

I would especially like to acknowledge Pamela Lalonde and Pepe Avila, who provided needed companionship, conversation, and considerable car mileage to join me on trips to some of Europes most haunting and remote memorials. Thank you!

Finally, I would like to thank my family: my parents, Patricia and Regis, my sisters, Julie and Jennifer, and my spouse, Garrett, all of whom have been travel companions at various times to the sites explored here but, more important, who have been a constant source of support. This book is dedicated to them.

Introduction

The Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum saw record attendance in 2016, receiving more than two million visitors from all over the world. There have been so many tourists to Auschwitz since its establishment as a memorial in 1947 that the concrete steps in the former barracks, now the main exhibition halls, have been worn smooth and concave from heavy foot traffic. Since 1999, when the memorial museum launched its website, the number of tourists to Auschwitz has climbed dramatically. It is tempting to read Dr. Cywiskis comment as self-referential, as if the description of controlled madness applies as much to Auschwitz tourism as to the events the museum commemorates and documents.