The Big Gray Truck

Nada, my dear,

Tomorrow morning I leave for the camp. Nobodys forcing me to go and Im not waiting to be summoned. Im volunteering to join the first group that leaves from 23 George Washington Street tomorrow at 9 a.m. My family are against my decision, but I think that you at least will understand me; there are so many people in need of help that my conscience dictates to me that I should ignore any sentimental reasons connected with my home and family for not going and put myself wholly at the service of others. The [Jewish] hospital will remain in the town, and the director has promised that he will take me in again when the hospital moves to the camp. I am calm and composed and convinced that everything is going to turn out all right, perhaps even better than my optimistic expectations. I shall think of you often; you knowor perhaps you dontwhat you have meant to meand will always mean to me. You are my most beautiful memory from that most pleasant period of my lifefrom the [Literary] Society.

Nada, my dear, I love you very, very much.

Hilda

7 December 1941

The inmates at Semlin were mostly women, children, and the elderly, as the male able-bodied Jewssome eight thousand of themhad by fall 1941 already been systematically shot in a wave of reprisal killings the Germans instituted as retribution for the casualties Yugoslav antifascist resistance was inflicting on the Wehrmacht. Hildas letters to Serbian friends back in Belgrade described horrific conditions in the camp and the increasing desperation and fatalism of the inmates.

Semlin was not a site hidden from view. It sits right across the River Sava from downtown Belgrade, and many witness testimonies confirmed that citizens of Belgrade could see Semlin inmates crossing the frozen river during the winter to bury their dead in the Jewish cemetery. During one of these crossings, Hilda Daj even arranged to see her friend Mirjana Petrovi for a minute and exchange a few words. While life under the occupation in Belgrade continued with some degree of normalcy, the Semlin inmates represented no more than small dots on the frozen surface of the river to the citizens of Belgrade.

Sometime between her last letter, written in early February 1942, and May 1942, Hilda Daj stepped into a large, dark, gray truck. She was likely told that she was designated for transport to another camp, and that she needed to pack her belongings and label her suitcase, which was loaded onto another truck. The large gray truck, however, was a mobile gas van, which the Germans euphemistically called the delousing truck (Entlausungswagen). This was a retrofitted truck with a hermetically sealed compartment that pumped carbon monoxide from the exhaust pipe into the interior of the truck, turning it into a makeshift gas chamber. Hilda would have been one of between fifty and a hundred Jewish inmates from Semlin who were driven in this van through the center of Belgrade, in plain view of Belgrade passersby, for ten to fifteen minutes at a time which was how long was needed for the gas to take effect. The truck would then drive on to Jajinci, a killing site on the outskirts of Belgrade, where the prisoners from other camps would dump the bodies from the van into mass unmarked graves.

By May 10, 1942, the two SS officers in charge of the operation, Wilhelm Gtz and Erwin Meyer, had taken between sixty-five and seventy trips in the van, killing around 6,300 Jewsalmost every single inmatedetained at Semlin.

In June 1942, Emanuel Schfer, the head of the German Security Police in Serbia, reported back to his supervisors, Serbien ist Judenfrei (Serbia is free of Jews), as almost all of Jews in occupied Serbia had already been killed, less than a year since the beginning of the German occupation. Belgrade was thus the first European city, and Serbia only the second Nazi occupied territory (after Estonia), to carry this macabre designation. The only Jews who remained alive were either in hiding, often in the countryside, or had joined the partisan resistance.

The Semlin camp is also a site of considerable importance for the larger historiography of the Holocaust, as it marks the period of particular intensification in the killing of European Jews. also the central site in the topography of the Holocaust in Serbia, as half of all Serbian Jews were killed there within a few short months in the spring of 1942.

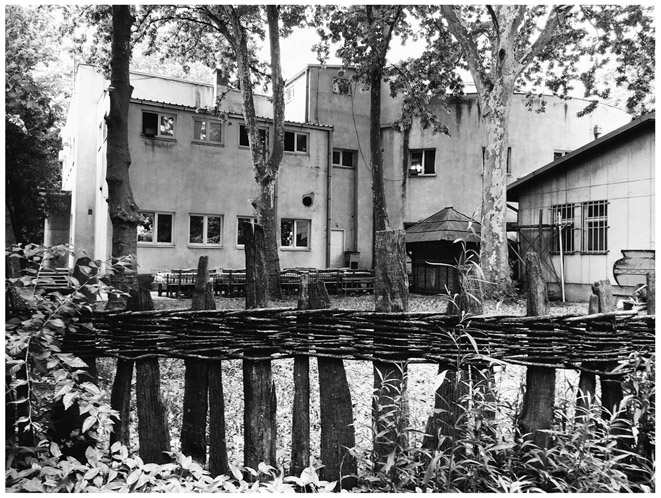

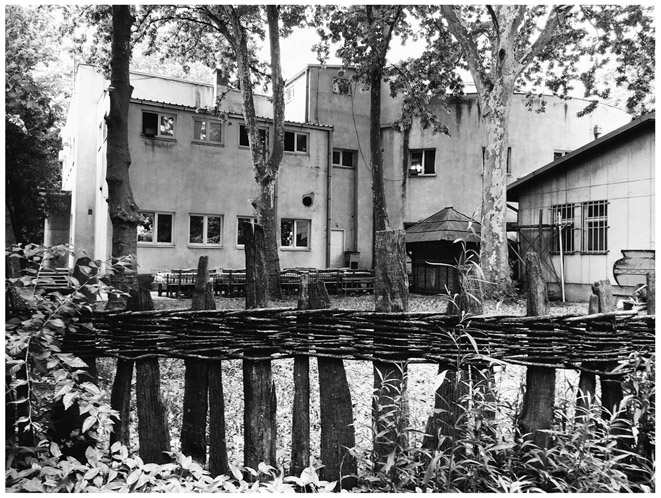

And yet, as of 2019, the Semlin camp site is a grotesque site of nonmemory. At least five buildingsout of the total of thirteen that made the Sajmite complexwere partially or completely destroyed in the allied bombing of Belgrade in April 1944 and were demolished after the war. The remaining buildings have been taken over by overgrown foliage, dumped trash, stray animals, and wasp nests. The buildings are crumbling, some populated by indigent squatters, some by artists who repurposed the buildings into studios (and some also into ramshackle living quarters). Some have turned into small businessesthere is a car mechanic shop, a bodega, a storage facility of some kind, an abandoned, overgrown, and depressing looking childrens playground. The shining new shopping center Ue glitters through the treetops.

The most prominent building of what remains of the site, the Central Tower, is abandoned and in ruins. For many years, the former Spasi Pavilion, the architectural jewel of the 1930s Belgrade Fairgrounds, housed a nightclub, which hosted a number of rock concerts, including a high-profile performance by Boy George in 2006, followed by an international boxing match in 2007. The nightclub has since closed and the gym Poseydon, which offers weightlifting, fitness, mini soccer, and martial arts, has taken its place. A small restaurant has opened outside. Another restaurant on the site, So i biber (Salt and pepper), occupies the former Turkish Pavilion, which served as the Semlin camp morgue. The restaurant website advertises itself as located on a small street, tucked in foliage, with extremely generous portions, available parking, and free Wi-Fi. The story of the Semlin camp, as well as that of the larger Holocaust in Serbia, remains almost entirely outside of Serbian public memory.

And yet, the Holocaust imagery is everywhere. In 2014, the Historical Museum of Serbia put up a highly publicized exhibition titled In the Name of the PeoplePolitical Repression in Serbia 19441953, which promised to display new historical documents and evidence of communist crimes, ranging from assassinations, kidnappings, and detentions in camps to collectivization, political trials, and repression. What the exhibition actually showed, however, were random and completely decontextualized photographs of victims of communism, which included innocent people but also many proven fascist collaborators, members of the quisling government, right wing militias, and the Axis-allied Chetnik movement. But the most stunning visual artifact was a well-known photograph of prisoners from the Buchenwald concentration camp, including Elie Wiesel, taken by US soldier Harry Miller at the camps liberation in April 1945. In the Belgrade exhibition, this canonic image was displayed in the section devoted to a communist-era camp for political prisoners on the Adriatic island of Goli otok.

FIGURE 1. Restaurant at the site of the former Semlin death camp, Belgrade, Serbia (photograph by author)

This equation of communism and fascism, and then the appropriation of Holocaust remembrance and imagery to delegitimize communism, is hardly an indigenous post-Yugoslav invention. This process has occurred throughout Eastern Europe, with much historical revisionism resulting from the attempts of Eastern European countries to deny or cloud their participation in fascist crimes, including the Holocaust, by elevating communist crimes to the level of the Holocaust, by delegitimizing antifascism, and in so doing legitimizing resurgent neofascism.