Copyright 2023 by Cornell University

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu.

First published 2023 by Cornell University Press

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

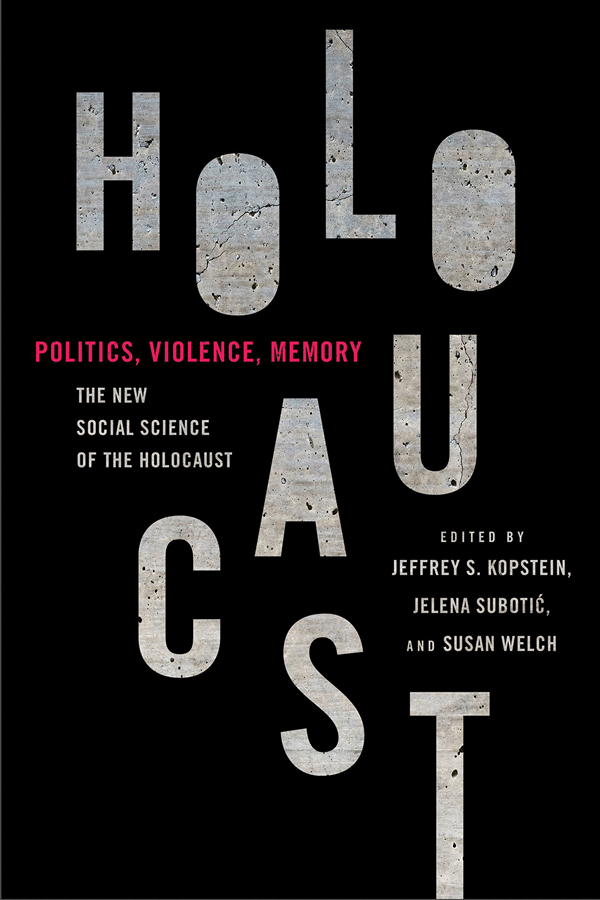

Names: Kopstein, Jeffrey, editor. | Subotic, Jelena, editor. | Welch, Susan, editor.

Title: Politics, violence, memory : the new social science of the Holocaust / edited by Jeffrey S. Kopstein, Jelena Subotic, and Susan Welch.

Description: Ithaca : Cornell University Press, 2023. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022016908 (print) | LCCN 2022016909 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501766749 (hardback) | ISBN 9781501766756 (paperback) | ISBN 9781501766763 (pdf) | ISBN 9781501766770 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)Historiography. | Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)Research. | Social sciences and history. | Social sciencesResearch. | Interdisciplinary research.

Classification: LCC D804.348 . P64 2023 (print) | LCC D804.348 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/180722dc23/eng/20220609

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022016908

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022016909

In memory of Susan Welch

Preface and Acknowledgments

This books journey began with two observations. The first was our sense that until recently, social science had largely ignored the Holocaust. We found this puzzling because so many of the concepts and theories in contemporary social science had their origins in the aftermath of the destruction of European Jewry. Even with this broadly acknowledged foundational background to modern social science, it is remarkable how few social scientists devoted their scholarly energies to understanding and explaining the causes and consequences of the event itself. There were, of course, important exceptions, but the relative silence of our own disciplines stands in stark contrast to our colleagues in history departments, whose many years of research on the Holocaust has yielded an outpouring of important scholarship.

Our second observation was that, over the past decade, things have started to change. Social scientists from a broad spectrum of disciplines, especially political science and sociology but also demography, economics, psychology, geography, and public health, have begun to ask new kinds of questions, adduce new evidence, and develop new theories and methods for understanding the sources, processes, and impact of the Holocaust. In doing so, they have not only added new layers of understanding to the mass killing, but also initiated the important work of reintegrating the study of the Holocaust into the mainstream of social science. Our goal in editing this book, therefore, is to showcase some of the more interesting contributions to this new research and to set the stage for further inquiry.

The contributors to this volume bring the distinctive scholarly methods and theories of their fields, but all remain committed to the twin projects of Holocaust research and theoretical advancement. These twin commitments may leave purists among historians and social scientists dissatisfied, but both projects enrich each other, and each one, we maintain, would be impoverished without the other.

The chapters were originally presented as papers at a conference, The Holocaust and Social Science Research, held at the University of California, Irvine on January 2122, 2020, just before the university moved to fully remote operations in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. They were substantially revised after several rounds of comments. We thank the contributors to and participants in the conference, especially those who gave important feedback on the papers. We were fortunate not only to have convened just in time, but also to have had the financial assistance of UCIs School of Social Sciences, Center for the Study of Democracy, and Center for Jewish Studies. Beyond UCI, we thank Georgia State University, especially the Center for Human Rights and Democracy, for financial support, and Saad Khan for editorial assistance. The Pennsylvania State Universitys College of the Liberal Arts, Jewish Studies Program, and Department of Political Science also provided generous support.

We also owe a debt of gratitude to our editors at Cornell University Press, Roger Haydon and Jim Lance, for their patience and for their confidence in this project.

Susan Welch passed away during the production of this book. A force within political science, Susan served for almost three decades as dean of liberal arts at Pennsylvania State University. In her final years she devoted her formidable scholarly energies to a deeper understanding of the Holocaust using the tools of modern social science. It is fitting, therefore, that this book is dedicated to her memory.

Jeffrey S. Kopstein

Jelena Suboti

Susan Welch

Introduction

A Response Delayed

Jeffrey S. Kopstein, Jelena Suboti, and Susan Welch

We live in a culture profoundly influenced by the legacy of the Holocaust. More than seventy-five years later, the Nazi extermination effort against the worlds Jews continues to provide the moral lens through which we judge political action. Debates about humanitarian intervention and foreign policy, democracy and authoritarianism, the politics of race, refugees, migration, and citizenship, and perhaps most importantly, our understanding of political violence have taken shape in the shadow of the destruction of European Jewry. The very categories we deploy to think about these mattersthe most famous example being the concept of genocidewere developed in an attempt to understand the magnitude of what had occurred and to prevent anything like it from happening again. The Holocaust therefore functions as a shadow case of sorts, a yardstick against which to compare a broad range of contemporary social and political processes. And yet, despite the centrality of the Holocaust to the way social scientists think about todays world, study of the event itself and its aftermath has remained largely peripheral to the social sciences, such as economics, geography, political science, psychology, and sociology.

How can we account for the relative absence of interest among social scientists in what is surely the index case of violence in the modern era? Explaining silence is not easy, but it is perhaps helpful to recall that research on the Holocaust did not commence immediately after 1945. There was a significant delay. Today we tend to think of the Holocaust as the most important aspect of World War II, but this intuition is one of recent vintage.

Perhaps understandably, the early studies of the Nazi regime came not primarily from historians but from German social theorists and philosophers, such as Franz Neumann (1942), Hannah Arendt (1951), and Gerald Reitlinger (1956), who explored how modernity could generate such monstrous outcomes.

But the social sciences remained remarkably silent. In fact, since the early 1950s, social scientists have largely ignored the Holocaust. In this introduction, we begin by outlining some possible professional, political, and demographic reasons for social scientists limited attention to the Holocaust. While the family of social sciences is large, our focus is primarily on political science, sociology, and demography. We first discuss the analytic framework that has developed to enable these social scientists to begin to make significant contributions to our understanding of the Holocaust, a framework that complements but does not displace the pathbreaking work of Holocaust historians. We then turn to the importance of social scientific research. Sustained social scientific engagement with the Holocaust, we maintain, will benefit our various disciplines, our understanding of the Holocaust, and the new generation of scholars ready to take up this challenge.

Next page