All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017. Printed in the United States of America

Names: Gennari, John, author.

Title: Flavor and soul : Italian America at its African American edge / John Gennari.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016029051 | ISBN 9780226428321 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226428468 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Italian AmericansEthnic identity. | Italian AmericansSocial life and customs. | African AmericansRelations with Italian Americans. | Popular cultureUnited States. | United StatesEthnic relations.

Classification: LCC E184.I8 G43 2017 | DDC 305.85/1073dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016029051

In memory of Remo Nicholas Gennari (19262011) and Clara Maria Dal Cortivo Gennari (19282015)

Who Put the Wop in Doo-Wop?

There was something about the sight of those four Italians, decked out in city slicker clothes, snapping their fingers and acting like Negroes, that must not have set too well with the folks in the Midwest. We were kind of exotic, which meant foreign, and that, in turn, meant dangerous.

DION DIMUCCI , on his appearance with Dion and the Belmonts on American Bandstand in 1958

My dream was to become Frank Sinatra.

MARVIN GAYE

Negroes and Italians beat me and shaped me, and my allegiance is there.

AMIRI BARAKA , The Death of Horatio Alger

Three scenes to set the stage and establish the tone:

I

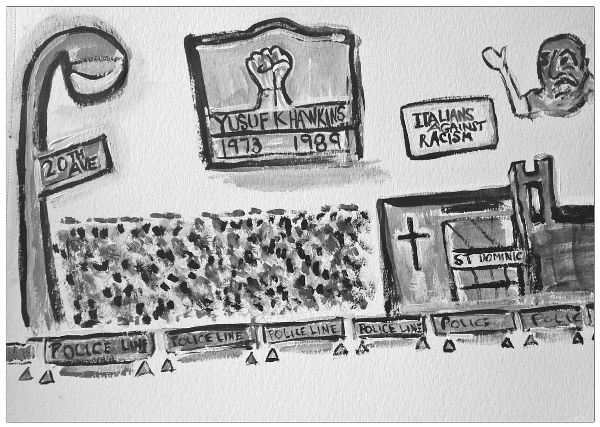

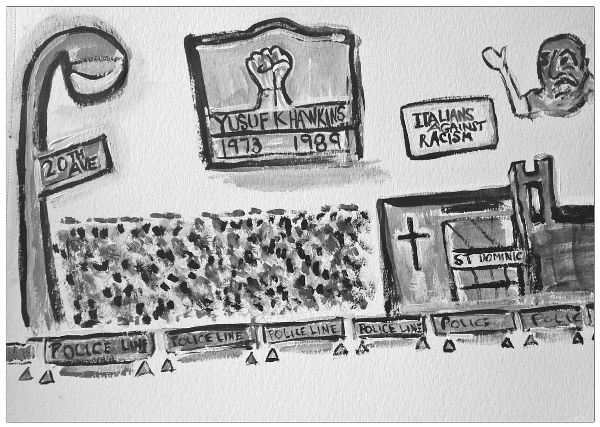

August 27, 1989. Bensonhurst, a predominantly Italian neighborhood in the southern part of Brooklyn. Four days earlier, a group of four African American teenagers from Bedford-Stuyvesant, a black neighborhood a few miles away, had come to look at a used car. A group of some thirty men, mostly Italian American, accosted them. In the chaos that ensued, a young man from the Italian posse shot and killed one of the young black men. On this day, a group of demonstrators meet at the site of the murder, Bay Ridge Avenue at the corner of Twentieth Avenue, for a prayer service in honor of the victim, Yusuf Hawkins, followed by a protest march up Twentieth Avenue. A newspaper estimates that there are 100 marchers, 250 policemen, and 400 counterdemonstrators on hand. The latter, almost all Italians from the neighborhood, hurl racist slurs at the mostly black demonstrators. Many wave Italian and American flags. Some hoist watermelons as they spit out their taunts; these tend to be younger men who walk, talk, dance, and occupy public space in ways that combine an older mode of Italian American street toughness with newer, fresher stylizations drawn from hip-hop music and the wider field of black urban youth culture.

One of the demonstrators that day is an Italian American graduate student named Joseph Sciorra. A native of Brooklyn and a student of local Italian American culture (later the author of the essay whose title I have borrowed for this introduction), Sciorra has been deeply disappointed by what he regards as obtuse and defensive responses to the tragedy from Italian American politicians and community leaders. To show his solidarity with the demonstrators, Sciorra shows up with a homemade poster board sign that reads Italians against Racism.

My use of the plural was a simple expression of hope, Sciorra would later write. What he encounters in Bensonhurst that day does little to nourish that hope:

My sign and my whiteness in the midst of the predominately black demonstration got the attention of the Italians lining the sidewalk. People pointed in my direction, laughing, cursing, spitting. Some clearly thought it was a ludicrous proposition: Italians against racism. Others were incensed. My cardboard placard called into question the popular notion that joined Italian American identity and racial hatred in some natural and essentialist union. I was a race traitor, an internal threat to the prevailing local rhetoric.

Figure 1. Bensonhurst-born New Yorker Stephanie Romeo joined Joseph Sciorra on his Italians against Racism march. Later she did this painting, March for Yusuf, Sunday, August 27, 1989. (Courtesy of Stephanie Romeo.)

II

November 14, 1998, the final day of a conference at Hofstra University called Frank Sinatra: The Man, the Music, the Legend. Coming just months after Sinatras death, the conference has generated unprecedented media buzz for an ostensibly academic gathering. Joining professors and graduate students among the thousands in attendance are musicians (Vic Damone, Milt Hinton, Joe Bushkin, Monty Alexander, Al Grey, Bucky Pizzarelli, Ervin Drake), writers (Gary Giddins, Will Friedwald, Nick Tosches), celebrities (former Los Angeles Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, comedian Alan King), media and music industry professionals from across the globe, and a legion of devout Sinatraphiles. After I deliver a paper about Sinatras relationship with his formidable mother, I am greeted by a woman of my own mothers generation up from Philadelphia. After an exchange of pleasantries, she wraps me in a big hug and plants a kiss on each cheek.

Later in the conference I present a second paper, this one focused on hip-hops appropriation of Sinatra as an icon of stylish, renegade masculinity, what black men call an OG (original gangster). Im on a panel that includes a fellow scholar who talks about Sinatras use of profane and aggressive language as a weapon of ethnic retribution and another who discusses sexual innuendo in Nice n Easy, Witchcraft, and other Sinatra songs. The Philadelphia woman, all ears in the front row, is not happy. No sooner does the audience Q&A kick off than she stands up to speak with fierce righteousness about coming from a family and community that revere Sinatra as a great Italian on the order of Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. I did not drive all the way up here from Philadelphia, she says, seething, to hear this great man disgraced with talk ofnow she points her finger at the defamers of the tribe seated on the daisswearing, sex, and... and... mobsters.

For our panel, the scene is not unprecedented or even surprising. We have attended many Italian American studies conferences whose mission is to counteract or, better, transcend Italian American stereotypesconferences, alas, at which people routinely cry, break into song, kvetch about the food, read poems about their saintly or demonic mothers, and promise retribution for this or that

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).