All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

The right of Steven Gauge to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details telephone Summersdale Publishers on (+44-1243-771107), fax (+44-1243-786300) or email ().

Chapter 1

Little Legs

Oxford psychology professor the late Michael Argyle said that the happiest people in the world were those who were either active members of a religious group or those who took part in team sports. So it was that at the age of thirty-five, as a miserable atheist, I took up playing rugby.

I hadnt played any rugby since I was about thirteen at school in Wimbledon. Even then I hadnt really played very much at all. For several years I convinced the rowing teachers that I was playing rugby, whilst convincing the rugby teachers that I was doing rowing. Meanwhile I went home and did very little indeed.

If you are no use at sport as a child you will be cruelly mocked and ridiculed. Those who are not particularly well co-ordinated and have thin skins will eventually give up and go away to find some other activity, like shoplifting or solvent abuse. However, when you take up a team sport like rugby as an adult, even if you have absolutely no idea what you are doing, no one gives you a hard time. People are just pathetically grateful that you have turned up. They are nice to you because you have made up the numbers so that they can have a proper game. If you add to that a willingness to play in the front row, they can have contested scrums and you will have made some friends for life.

Rugby seemed to be a great place to deal with my own personal midlife crisis. I was in a relatively senior job in a large chamber of commerce and government-funded business support operation. Having spent the earlier part of my career in a more metrosexual media and political environment, I was now surrounded by some very blokey blokes; they were all either go-getting entrepreneurial types, or failed businessmen who had become business advisers. Most seemed to spend their days talking about sport and cars. If I was going to get on with this crowd, as the saying goes, I needed to man up.

I had also recently acquired contact lenses after a lifetime in glasses in a bout of midlife vanity. It could have been worse: others of my generation were bleaching their hair, getting inappropriate piercings and wearing leather trousers. Contact lenses paved the way to contact sports.

So when I found my way to Warlingham Rugby Club, I was delighted to discover a home for a group of men, all enjoying their own particular mid, early or later life crises and having a good time into the bargain. Here, by a Surrey playing field in the late summer, I found my way to the changing rooms and pulled on my newly purchased boots.

Warlingham is like many rugby clubs in the UK. There is a nice enough clubhouse with a huge function room, a cosy bar and some basic, bare-brick changing rooms. It prides itself on being one of the few clubs with a huge traditional communal bath. It has five pitches and shares the premises with a netball team and a cricket club. Every now and again someone will apply for some lottery money, send out an appeal or send off an insurance claim and a few improvements or repairs will be done by someones mate.

There is a floodlit training pitch and on a Tuesday and Thursday evening throughout the autumn, winter and spring, men of various shapes and sizes turn up for training.

Its only when you look at the car park on a training night that you realise the wide range of people that get involved. One of the joys of amateur club rugby is the diversity of the sorts of people who play. From city boys who turn up in suits and smart cars, to builders and landscape gardeners who turn up in battered Ford Transit vans, once everyone is changed and on the pitch your background is almost irrelevant. Traditional British social divisions are replaced by a far more sinister and uncrossable barrier, rugbys very own apartheid: the distinction between forwards and backs.

That was the first tricky decision I had to make at my first training session. After a bit of running around to warm up we were told to divide up into forwards and backs. Which was I? I had absolutely no idea, and no time to decide. As far as I could tell, from watching the odd international on the TV, the forwards seemed to have to do a lot of fairly technical stuff: scrums, line-outs, rucks, mauls, ear-biting, eye-gouging etc. These were dark arts of which I knew nothing. The backs seemed to have a fairly straightforward job of standing in a line, throwing the ball to each other and running a bit. How hard could that be? I decided to be a back.

The coach for that evening was a nice bloke called Neil Farmer, a ponytailed schoolteacher (pottery, I guessed), tall and thin with a good line in sarcasm. He took one look at me as I jogged off to join the backs and, with his eyebrows making a bid for freedom off the top of his head, said, Are you sure?

Im not a hugely tall person and the modest belly that I carry around with me for comfort and protection is ever so slightly out of proportion with my height. The coach, as might anyone else, looked at me and saw an overweight hobbit who ought to be in the front row, if anywhere at all.

However, I stuck with the backs for the first session. A seventeen-year-old with enormous patience told me where to stand, when to run and what to do if I caught the ball. We ran around a bit and passed the ball to each other. In the words of Aleksandr the Meerkat, Simples.

One of the things that have impressed me about club rugby is that I cant think of many other situations where a middle-aged fat bloke can interact socially with hoody-wearing teenagers. Probably the only other time it happens is when youre being mugged. Talking to teenagers is normally unbearably painful. Add a rugby ball into the equation, however, and suddenly it seems to work. It turns out that they can actually be quite pleasant. The young man who looked after me at my first session on the playing fields of Warlingham Rugby Club did a great job and Ive never looked back.

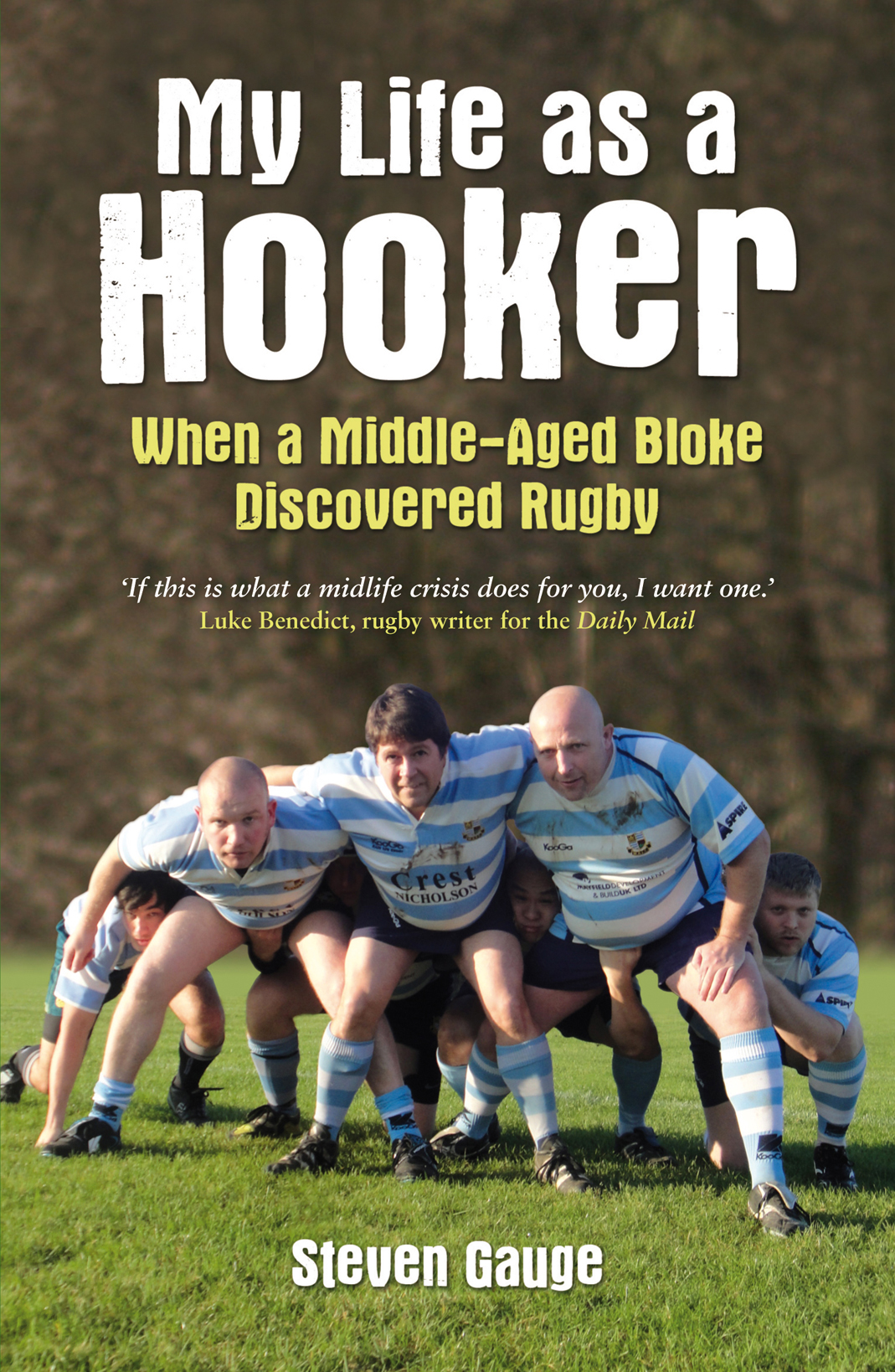

I did quickly realise, however, that I was never going to be a back. There really was an awful lot of running around involved. An independent assessment of my physique by the third-team captain, Mark OConnor, suggested that I was the perfect stature to become a hooker. Thats the chap in the middle of the front row of the scrum who has the job of hooking back the ball with his foot, so that it pops out of the back of the scrum into the grateful hands of the scrum half.