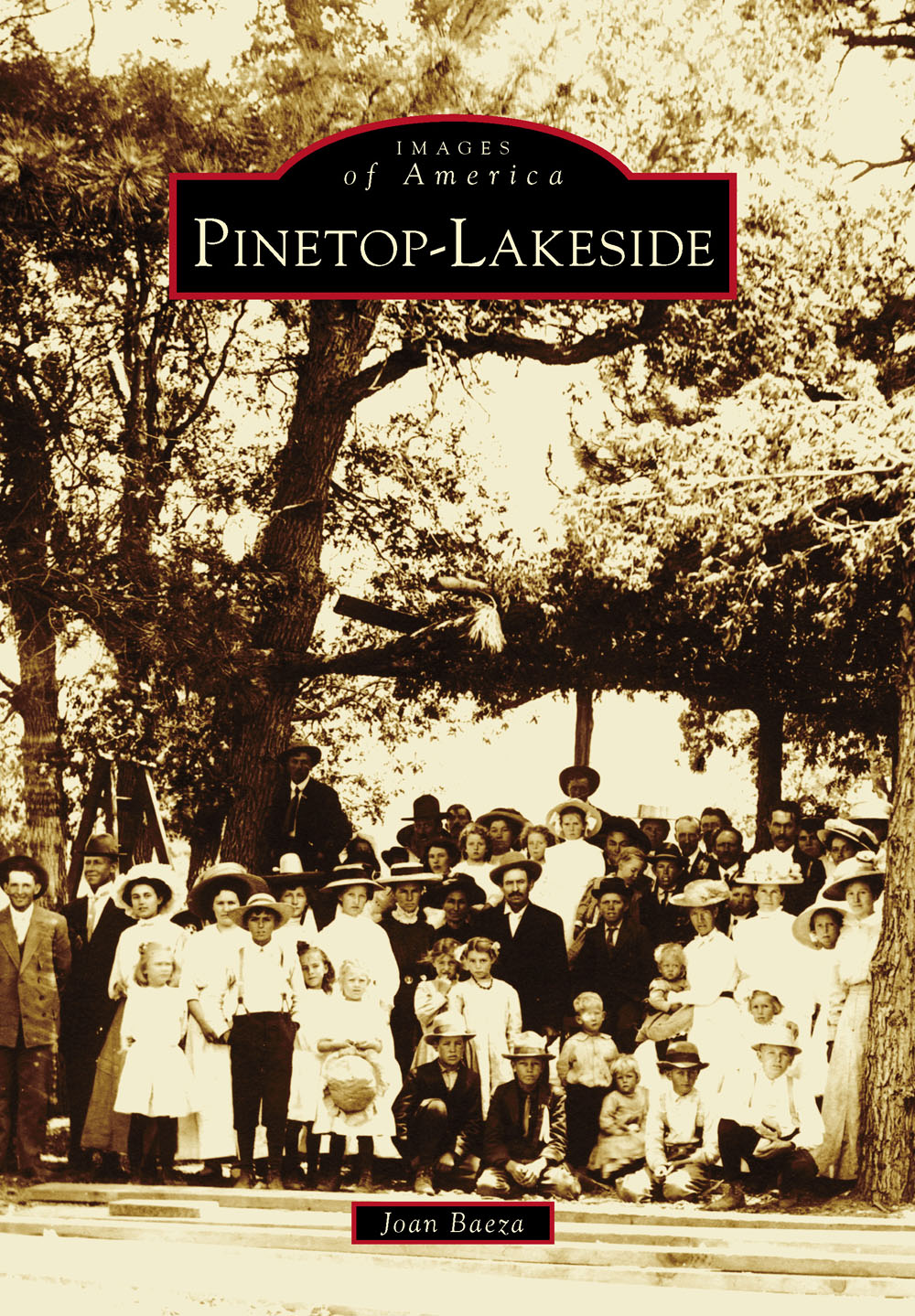

IMAGES

of America

PINETOP-LAKESIDE

The people are going to miss the frontier more than words can express. For four centuries they heard its call, listened to its promises, and bet their lives and fortunes on its outcome.

Walter Prescott Webb

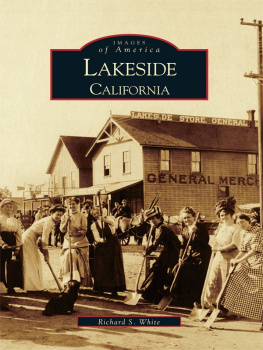

ON THE COVER: Lakeside pioneers pose for a picture in their Sunday best at the Bowery, an outdoor pavilion with a plank floor and brush roof supported by wooden poles. Before the Latter-day Saints were able to build a church, they held services at the Bowery in summer and in the schoolhouse in winter. The structure was also used for dances, picnics, and other gatherings. (Courtesy Louise Willis Levine.)

IMAGES

of America

PINETOP-LAKESIDE

Joan Baeza

Copyright 2014 by Joan Baeza

ISBN 978-1-4671-3216-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439649015

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014932394

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Lovingly dedicated to Paula and Bill.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I could not possibly have written this book without the help of at least 100 other people. I do not have space to thank each person individually, but I hope those I left out know how grateful I am for their willingness to share their pictures and stories.

Special thanks are in order for research assistant Jim Snitzer, who volunteered to scan all the images. I owe him a dinner at Charlie Clarks. Many thanks to Marion Hansen, who shared pictures, journals, and diaries he has collected of Lakeside pioneer families.

Some contributors were the direct descendants of early Pinetop-Lakeside pioneers, including Ferrell Fish, Raymond Johnson, Sue and Sonny Penrod, Jack Reed, Bobbie Stephens Hunt, Anthony Cooley, Lonnie Amos West, Pam Fish-Tyler, the Webb family, Arlene Mcabe, Louise Willis, Loretta Lee Jennings, Nancy Stone, Renee Penrod, Anna Jackson, Hazel West Fish Gillespie, Arlene Fish McCabe, Leo Petersen and Wanda Petersen Tenney, Louise Johnson McCleve, Norma Larson, Melba and Anna Gardner, Anne Snoddy-Suguitan, Maryann Scorse Coulter, and Craig Hansen.

Thanks to Jack Wood of White Mountain Computers, who kept my computer cruising and contributed images.

Professional photographers who graciously gave me permission to use their photographs were David Widmaier, Vennie White, Lloyd Pentecost, and Judi Bassett. Steve Taylor and Bill Lundquist contributed original artwork. Author Gene Luptak shared photographs and information from his book Top o the Pines. Author Robert Moore sent us digital images from The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arizonas Rim Country. Greg Tock, editor and publisher of the White Mountain Independent, not only let us use his copyrighted images, he also tracked them down! Some of the contributors with second- and third-generation connections to Pinetop-Lakeside are Gary Butler, Gary Renfro, Gloria Guenther, Diana Butler, Georgia Dysterheft, Jo Ann Hatch, Maxine Ann Turnbull, and Julie Wilbur West.

First-generation Pinetop-Lakeside contributors include Bev Garcia, Bonnie Lane, Bill and Tricia Gibson, Mary Ellen and Chuck Bittorf, Ginny and Jerry Handorf, Brenda Mead Crawford, Julie Aylor, Johnnie Fay McQuillan, Mark Sterling, Dwayne Walker, Kevin Rowell, Betty Jarrett, Lynda Marble, Phil Hayes, and Geoff Williams.

Federal, state, and local agencies have been of great help, especially the USDA-Forest Service, the Arizona Game and Fish Department, the Pinetop Fire Department, the Lakeside Fire Department, and the Pinetop-Lakeside Police Department. The White Mountain Sheriffs Posse provided many good images.

Public institutions are always major contributors to a book like this, and I thank the Navajo County Library District, the Pinetop-Lakeside Library, the Snowflake Heritage Foundation, the Pinetop-Lakeside Historical Society Museum, the Victorian, and the Show Low Historical Society Museum.

My thanks go out posthumously to historians Leora Petersen Schuck and Ben Hansen for their many wonderful stories of the Lakeside pioneers.

Most of all, I thank God for creating this beautiful place.

INTRODUCTION

For longer than anyone can remember, people who love the outdoors have called Arizonas White Mountains Gods Country. In modern times, they come in waves to fish, hunt, camp, hike, and backpack, ride ATVs, snowmobiles, and horses, scale mountains and canyons, golf, ski, cut Christmas trees, bird-watch, observe wildlife, and take pictures. They come to restore their souls in the pine-laden air.

The town of Pinetop-Lakeside is a gateway to this mountain paradise. Approximately 4,200 people call the incorporated area home, but cabins and country clubs are scattered throughout the surrounding forests and woodlands. For a small town, the population is surprisingly cosmopolitan. People congregate at barbecues, chili cook-offs, festivals, art shows, concerts, and sports events. They come to eat, drink, and converse at one of many good restaurants. Scarcely a week passes without a public benefit of some kind. Mountain people help each other.

Those who live here call it simply the mountain. They live and work and grow old by the seasons. They live on the mountain because they want to. It is not unusual to find a fifth-generation descendant of a pioneer family living here. They go away, but they come back.

Pinetop-Lakeside is the headquarters for the Lakeside Ranger District of the two-million-acre Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests, whose lands range in elevation from around 6,000 feet in the pion-juniper woodlands, to forests of pine, spruce, and fir on the 11,400-foot-high Mount Baldy. The A-Bar-S, as it is known locally, nurtures 24 lakes and reservoirs and more than 700 miles of trout streams.

The southern boundary of Pinetop-Lakeside borders the Fort Apache Indian Reservation, the traditional homeland of the White Mountain Apache Tribe. The 1.6-million-acre reservation was once much larger, including land now belonging to the town. The past, present, and future of reservation and off-reservation communities are intertwined. Tourists fish and camp on tribal lakes and streams, hunt trophy elk, ski at Sunrise Resort, dine at Hon-dah Casino and Convention Center, and work, teach, and drive on tribal lands. Tribal members shop, eat out, work, go to movies, attend school, and often live in Pinetop-Lakeside. Tribal and non-tribal law enforcement, as well as fire and emergency services, work together under cooperative agreements.

Humans have left their footprints in these mountains for as long as 14,000 years. Ancient hunters passed this way. Except for stone artifacts and signs of campsites, the hunters left no trace. The first distinct culture archaeologists recognize in the White Mountains is known as Mogollon. These ancestors of Hopi and Zuni people cultivated corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers, domesticated wild turkeys, and made pottery. They traded with people as far away as Central America and California. By 1450 a.d., they had moved on. Archaeological evidence suggests that Athabaskan-speaking people began to drift into the Southwest in small bands from the north around the same period that the Ancestral Pueblo people left.

The first known presence of Europeans in the White Mountains was Francisco Vazquez de Coronados expedition, which left New Spain in 1540 in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. Stewart Udall, in his book

Next page