What are the smells of kitchens alongside the Baltic Sea?

Every season is a bit different. A bit of the forest, the meadow, the sea, the rivers and lakes, the gardens and farms. A bit salty, because of the wind from the sea, the fishing nets and the buoys. A bit dizzying because of the forest, the mushrooms, the mint, the wild thyme, the sweet woodruff and the juniper berries. A bit sweet because of the sun-warmed wild strawberries, the evening fog in a field of rye, the honey that is produced by bees, the wax cells and linden blossoms. A bit spicy because of the alder smoke from the smokehouse, the blue cheese and hemp butter. A bit fresh because of the pickles, chopped dill and chives. A bit bitter because of the peel of new potatoes. A bit gentle because of the fresh milk, cream and cheese. A bit intriguing because of the caraway seeds, mustard and malt. A bit tempting because of the cinnamon, cardamom and chocolate that are used to make local delicacies. A bit strong because of the distilled drinks like aquavit and vodka.

What colours are found in the kitchens alongside the Baltic Sea?

White dairy products; black blood sausages; a rainbow of colours among the vegetables and berries; brown nuts, mushrooms, roasts, cakes and gingerbread; pink desserts; silvery and golden fish; orange pumpkins and seeds from white to black.

What sounds are heard in the kitchens alongside the Baltic Sea?

Crackling, crunching, sizzling, bubbling, boiling and quietly steaming.

What is the taste of foods alongside the Baltic Sea?

The most important thing is to strike a balance among the various flavours that come from nature, with regard to tradition and innovation, careful work and creative ease, comfort and elegant style. Take a bit from the east, the west, the north and the south. Taste cannot be described or written down so come and taste it yourself!

Sandra Oia

Honeys from the purest nectar, sour milks, black breads, poppy and hemp seeds, caraway and cabbages these are some of the many ingredients that first drew me to the wholesome, creative, practical and intensely seasonal world of Baltic cuisine.

Theres no personal backstory to my relationship with the Baltics, at least not in the typical sense. I have no old Lithuanian aunt who made curd cheese with me or served me kugelis as part of some unforgettable childhood meal. Instead, my motivation for writing this book comes from a respect for the people of the Baltic countries and a love for their food; it fascinates me to discover what we can learn about a people and their culture through whats on their table, to research beyond the ingredients that first pull me towards a cuisine and to discover more of a regions culinary landscape.

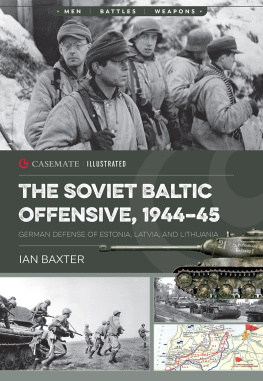

Hugging the north-east coast of the Baltic sea, the diminutive scale and shared recent history of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania has made many of us, albeit unintentionally, view them as a whole. Its these three countries that we think of when we hear Baltic. Russification came to the region in the 1930s and with it a period of Soviet rule spanning forty-seven years yet in the centuries prior to this era countries such as Germany, Sweden and Denmark also occupied the region. This, coupled with the regions position as a historic trading point with Byzantium (which brought it into contact with spices such as cardamom and cinnamon), has resulted in a cuisine that has many distinct influences, of which Russian and German predominate.

In spite of all this change, however, one factor has remained constant the society of the Baltic region has always very much been an agrarian one, with a respect for nature and what it yields that is still clearly evident in how its people eat today. The regions food markets are full of local, seasonal produce not because these concepts are popular, but because this is how its always been. This is a region where (at the time of writing at least) unpasteurised milk from small farms is still being poured from jerry cans into refillable bottles at the Riga Central Market. Its also a place where the local black bread is adored, where the potato reigns as king and where produce has traditionally been preserved as a means of necessity due to the vigorous, contrasting seasons and long winter months.

) also came about as a result of this creativity. Whats fascinating is that many of these foods, some of which we may find hard to relate to, are still loved and eaten regularly by Balts.

Much like their Nordic neighbours to the west, the Baltic countries are now experiencing a period of change as they re-evaluate their food identity. The term Post-Soviet Cuisine, the Baltics answer to New Nordic, is an accurate description of the direction of young chefs cooking today in the regions quickly growing restaurant industry. Some are ignoring their Soviet past, others embracing it, but they are all executing this change at a rapid pace with the same enthusiasm and no less quality as the Nordic countries.

Reflecting this exciting change, the food that features on the pages ahead is not intended to be a perfect facsimile of historic Baltic recipes passed down over generations. Rather the intent is to capture the spirit of Baltic cuisine as it is now, to make it accessible and to inspire you, the reader, to want to understand and cook it at home. Recipes may be plated and presented in a nontraditional manner; for example, a garnish that would never be used by a Balt might be added to a particular dish. Indeed, some recipes typical to specific regions may not appear the reason being that the selection here is based on my personal experiences, and features those recipes I feel will best pique the interest of readers outside these countries. This may irk some Baltic natives, but I hope that motivating interest in the regions culture and cuisine trumps the need to recite age-old recipes for the sake of authenticity.

On a personal note, making this book has been a discovery. Not only have I learned about the culture and customs of three unique and relatively unsung countries, but I have also become more aware of the profound role that nature plays within our food systems and cultures. Essentially for the Balts the changing of the seasons dictates what is eaten. The global systems we have put in place to transcend these seasons and manufacture what we want, when we want it are something that I feel we have become too comfortable with. Whether as a result of circumstance or choice, I admire these countries for how they have never let go of their seasonal approach. They havent raced along as fast as the rest of the world; ideas about sourcing food from nature at specific times havent left and come back they never left. As a result, when it comes to looking at how we all want (and need) to eat in the future, in many ways these countries are already way ahead of the rest of us.