Bitters make themselves known. You get a distinct impression when tasting them, unmasked and unadorned, in some seltzer water: challenging, but also familiar (weve all tasted bitterness), a foil for the more common flavors on the table. Here is an opportunity to invite juicy conversation. What are you thinking? What is this stuff? This tastes bad!

At first blush, we might agree. In the most superficial ways bitters taste bad. The most bitter plants, isolated, are nasty. Weve looked at all sortsfrom the milder rinds of citrus fruits to the truly awful andrographis plant, which comes off as a cross between tobacco, soap, and ashy dirt. But bitters are more than just these most intense botanicals: They are formulasrecipes balanced atop a bitter foundation, like an apple around its bitter core. These formulas, when blended into a cocktail or served as counterpoints at the dinner table, allow this most challenging flavor to come out, to be showcased and enjoyed. In so doing, they highlight the other ingredients even morefor what would the hero be without the villain? Or the weekend without the workweek? Would a great drink or a novel dish be complete without the bitter flavor to set it off?

THE BITTER TRUTH: WHAT SCIENCE SAYS

Enjoying a balance of flavors at the bar or dinner table is one thing. But there is interesting research that points to how incorporating the bitter flavor in our lives positively affects our eating patterns, too. Scientists at Italys University of Pavia (where bitter liqueurs, known as amari, are common) gave overweight adults a bitters formula containing artichoke leaves (up toward the top of the awfulness scale) or a placebo. During the study, which lasted two months, participants took the bitters before eating. By the studys end, those not on the placebo reported reduced appetite and consumption, along with lower cholesterol and blood sugar levels, and smaller waistlines.

Weve learned a lot about why this happens: Bitters change the way our guts work, especially when we taste them, making our stomachs feel fuller more quickly and affecting the secretion of enzymes that digest our food and the hormones that control our appetite. The deeper you dig, the more you find that omitting the bitter flavor really is like sleeping on the beach all dayyou feel sluggish, gain weight, and your digestion gets bored and shuts off.

This is why, in most intact food systems around the world, you see the judicious addition of the bitter flavor. From Italys amari and Indias bitter melon chutney, to Chinas bitters to cleanse the internal organs and Venezuelas fabled Angostura bark, these herbal formulas spark life, conviviality, and good health. In all cases, bitters are celebratory. They enliven meals and help with the consequences of feasting, not only reducing overconsumption, but also helping with indigestion, heartburn, bloating, and stomach upset. As such, bitters are often found as bookends to the mealtaken as an aperitif in sparkling water or a cocktail, and as a slow-sipping digestif (often in lieu of dessert). Todays clinical research validates these traditional indications.

Our current understanding is that, along with supporting healthy digestion, bitters also enhance the livers ability to flush inflammatory compounds and irritating substances from our bodiesespecially if used as part of a daily habit. In fact, bitters seem to be so good for liver function that ingredients such as milk thistle, a widely used bitter plant, have been tested for treating hepatitis, liver cancer, cirrhosis, and toxicity from drugs and alcoholall with consistently positive results.

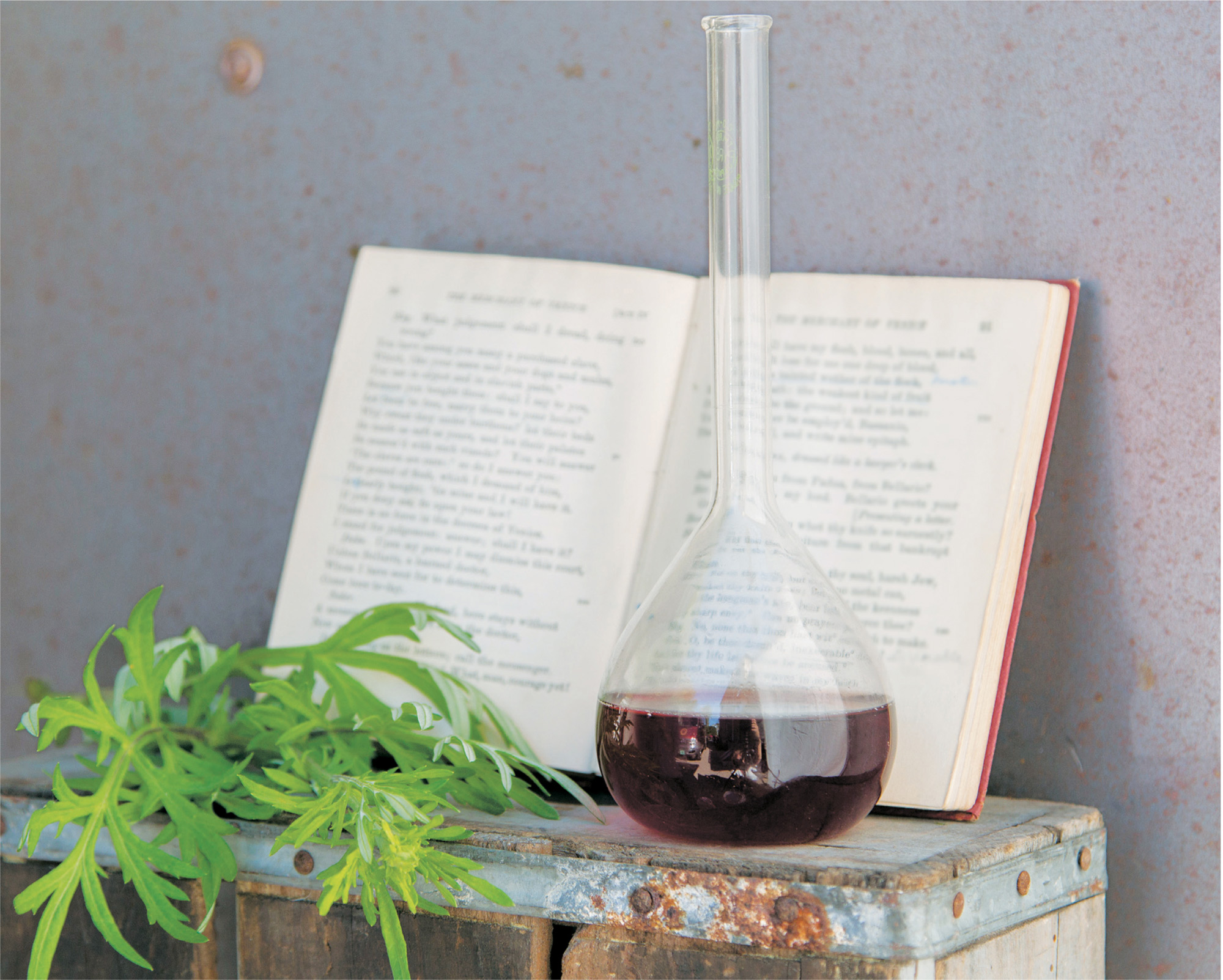

Healthier weight, smoother digestion, optimal liver function, and reduced inflammationthese are the benefits of engaging with the bitter flavor. But there may be another benefit, too, one that comes from the fact that many plants used to make bitters are wild and weedy. Bitter plants such as Artemisia genepi, source of the alpine gnpi bitters, are rare specimens found in remote mountain crags. They bring a wild tangle of plant chemistry into our bodies. When we embrace these bitter plants, we also help spread botanical diversity, increase options for pollinating insects, and fight back against the mind-numbing homogeneity of corn, wheat, and soy in the modern agricultural landscape. In this sense, making and taking bitters are ecological acts.

THE GREATER GOOD

Wild botanicals are, in fact, medicinal in a much broader sense. Free from human interventions such as hybridization and industrialized architecture, they remain jam-packed with flavor and a rich, diverse chemistryechoes of a foraging life now thousands of years in our past. When you bring them into your kitchen, you tap into not only an amazing flavor palette but also a phytochemical cocktail loaded with opportunities for encouraging a healthy, vibrant self.

As we explore what makes a great bitters formula, well first define a framework for flavor. Understanding the chemistry behind the individual tastes that go into a formula can help us plan synergies, get specific with extraction methods, and explore the ingredients medicinal effects. Then, we can use this background to create a general template for bitter blends, collect the tools needed, and gather ingredients for extraction and processing.

Most ingredients can be found in your local quality herb shop and at wine and spirits stores (additionally, see ). We strongly recommend getting to know each ingredient individuallyits history and value, flavor profile, unique chemistry, and extraction. Focusing on one ingredient at a time and then blending extracts into formulas teaches you to fine-tune recipes and create custom blends on the spot based on your tastes, seasonal variations, or medicinal value. You also get the best possible extraction of each component. We have included information on a wide range of botanicals (and other ingredients)ninety-two in allthat can serve as the core of your home research-and-development facility.