This book was edited by Dave Kirby and Karen Lewis, who provided invaluable assistance in this role.

Many other people provided assistance to me, without which the book might never have been written. Among them, I especially wish to thank Al Bagley, Bill Terry, Dick Hackborn, Barney Oliver, Art Fong, Dick Were, and my personal secretary, Gretchen Dennis, who helped to put it all together. Id like also to acknowledge the assistance of Margaret Paull, my secretary at the company.

The accuracy in this record is largely their contribution; the errors are fully my responsibility.

In the section about my involvement as the U.S. deputy secretary of defense, I have included only those activities that involved applying the HP Way in the DOD and some of the important management changes involving the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.

On August 23, 1937, two recently-graduated engineers met to consider the idea of founding a new company. They put their thoughts to paper, beginning with a general statement about design and manufacture of products in the electrical engineering field, followed by a startling statement: The question of what to manufacture was postponed...

Later, they brainstormed ideas, making a long list of product possibilities. They considered phonograph amplifiers. They considered air conditioning controls. They considered television receivers, welding equipment, and public address systems. They even considered medical equipment (making a special point to avoid quackery). So long as they could make a technical contribution, any product would be fair game to get the company out of the garage. In the months after that first meeting, the young engineers kept their start-up alive with contract projects, including an electronic shock jiggle machine to help people lose weight. Finally, they hit upon the audio oscillator and sold eight units to Walt Disney, earning the company its first substantial revenues.

In teaching a class on entrepreneurship at the Stanford Graduate School of Business in the early 1990s, I would start the first class session by reading the founding notes from the 1937 meeting, careful to disguise the names of the founders. Then Id challenge my students: Rate this start-up on a scale of 1 to 10, and jot down strengths and weaknesses of their approach. The average score would be about a 3, my MBA students blasting the founders for lack of focus, lack of a great idea, lack of a clear market, lack of just about everything that would earn a passing grade in a business plan class. Then Id say, Oh, one more little detail. The names of the founders were Bill Hewlett and David Packard.

The students sat in stunned silence. How could this be? But were taught that you need a clear understanding of how you will create competitive advantagea great idea for launching an enterprise.

But they had a great ideathe ultimate source of competitive advantageif you can just see it, Id push back. What might that be? After ten or fifteen minutes, someone would likely voice the key point: Bill Hewlett and David Packards greatest product was not the audio oscillator, the pocket calculator, or the minicomputer. Their greatest product was the Hewlett-Packard Company and their greatest idea was The HP Way.

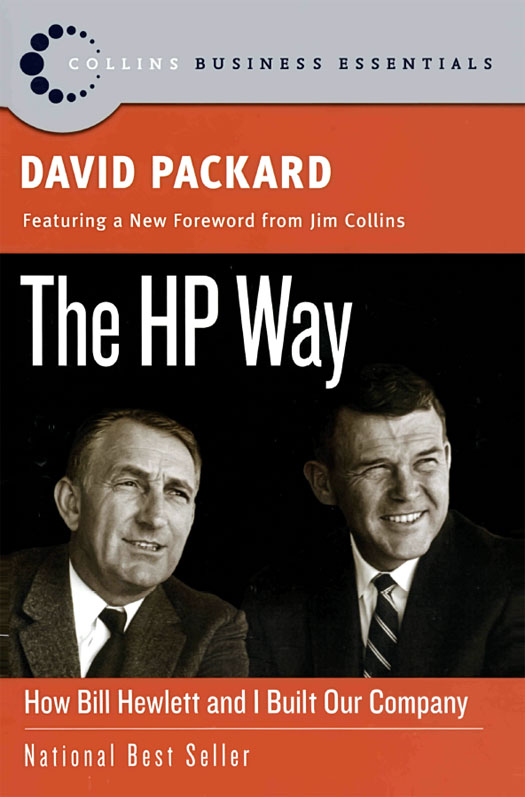

This wonderful book, which David Packard wrote shortly before his death, outlines the history of the company and the development of the HP Way. The HP Way reflects the personal core values of Bill Hewlett and David Packard, and the translation of those values into a comprehensive set of operating practices, cultural norms, and business strategies. The point is not that every company should necessarily adopt the specifics of the HP Way, but that Hewlett and Packard exemplify the power of building a company based on a framework of principles. The core essence of the HP Way consists of five fundamental precepts. 1) The Hewlett-Packard company exists to make a technical contribution, and should only pursue opportunities consistent with this purpose; 2) The Hewlett-Packard company demands of itself and its people superior performanceprofitable growth is both a means and a measure of enduring success; 3) The Hewlett-Packard company believes the best results come when you get the right people, trust them, give them freedom to find the best path to achieve objectives, and let them share in the rewards their work makes possible; 4) The Hewlett-Packard company has a responsibility to contribute directly to the well-being of the communities in which its operates; 5) Integrity, period.

Today, we take the tenets of the HP Way almost for granted, but when first formulated, they were visionaryindeed, quite radical for the times. In 1949, David Packard, attended a gathering of business leaders. As the day wore on, Packard became increasingly frustrated with the parochial, small-minded perspective of his fellow CEOs. Peering down from his 6 5 frame, the 37 year-old Packard voiced a contrary view: A company has a responsibility beyond making a profit for stockholders; it has a responsibility to recognize the dignity of its employees as human beings, to the well-being of its customers, and to the community at large. Packard later reflected in a 1964 Colorado College commencement speech: I was surprised and shocked that not a single person at that meeting agreed with me. While they were reasonably polite in their disagreement, it was quite evident they firmly believed I was not one of them, and obviously not qualified to manage an important enterprise.

Hewlett and Packard rejected the idea that a company exists merely to maximize profits. I think many people assume, wrongly, that a company exists simply to make money, Packard extolled to a group of HP managers on March 8, 1960. While this is an important result of a companys existence, we have to go deeper to find the real reasons for our being. He then laid down the cornerstone concept of the HP Way: contribution. Do our products offer something uniquebe it a technical contribution, a level of quality, a problem solvedto our customers? Are the communities in which we operate stronger and the lives of our employees better than they would be without us? Are peoples lives improved because of what we do? If the answer to any these questions is no, then Packard and Hewlett would deem HP a failure, no matter how much money the company returned to its shareholders.

Most entrepreneurs pursue the question How can I succeed? From day one, Packard and Hewlett pursued a different question: What can we contribute? and thereby HP attained extraordinary success. This success, in turn, enabled them to invest even more in making a contribution, which produced even greater success, which led to increased contribution, which created even greater success. This virtuous cycle eventually enabled Packard and Hewlett to personally contribute at levels far beyond what they would have dared to imagine as young men. In 1995, Packard attended a dinner at Stanford University. Former engineering dean Jim Gibbons mentioned to Packard that, by his rough calculation, he and Hewlett had donated on a present-value basis as much to Stanford as Jane and Leland Stanford had given to fund the university. As Gibbons related in the June 1996 issue of Stanford magazine, Packard showed something he rarely allowed: a moment of visible pride. It passed quickly, and all Packard said was, Thats very interesting. Later, upon his death, Packard bequeathed nearly all of his $5.6 billion estate to a charitable foundation.

But if you were to think of David Packard and the HP Way as being all about benevolence and charity, you would be terribly mistaken. Packard and Hewlett demanded