Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Translation and preface 2018 by Shambhala Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

TRANSLATORS PREFACE

Singapore Dream and Other Adventures is like a message in a bottle set afloat in Southeast Asian waters in 1911. The messenger is Hermann Hesse. The messagetwenty-one eyewitness reports, some poems, and a storyis his account of his voyage to Ceylon and the East Indies (as they were then called). This was Hesses actual journey to the East, the experience that became the basis for Siddhartha and his other famous novels. By 1911, Asia had been divided among the European colonial powers and was being wrung for its wealth. By bleeding its colonies for trade, the West was stirring to new ways a perennial Orient that had remained essentially unchanged for centuries, perhaps millennia. In 1911 the last imperial dynasty of China was on the brink of collapse. An enormous Chinese diaspora was in place in the lands where Hesse traveled, as well as an Indian one of lesser size. These old peoples and the indigenous Malays were being turned into servant populations, in some places marshaled into masses of cheap or forced labor, referred to by their colonial masters as coolies. Hesse arrived on a late swell of this massive sea change, rolling from West to East. As he traveled, he could see modern transformations kicking in as superficial layers of new over the old. He did not find the sight edifying.

Hermann Hesse was born in Germany in 1877. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946, most of his major works having been published long before that. Yet for many English-language readers his name is associated with the countercultural revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, with hippies, LSD, Kerouac, and so on. In 1969 many a copy of Hesses ninth novel Siddhartha (published 1922) might have been found lying about on couches in Haight-Ashbury or tucked into backpacks at Woodstock.

What did Hesse, a European writer of earlier decades, the scion of two generations of Protestant missionaries on both sides of his family, have to do with the seekers of the dropout generation? It was Hesses probing and intense descriptions of the struggle for authentic experience that reached them. Hesses characters rejected expected solutions for their lives and undertook the search for a new personal truth. Through this, Hesse spoke directly to that at once lost and joyous generation. He mirrored their spiritual hunger and explained their discontent with what they saw as a dead-ended, materialistic world. Above all, he showed them the shape of the spiritual journey by supplying the form of a journey to the East. Thus he at once confirmed their spiritual quest and gave it a place to go.

As happens with writers who touch a deep chord in human life, Hesses name and influence have endured. For Hesses legacy, it was never simply a matter of having caught the wave of a particular generation. His work did not belong to the counterculture revolution to begin with; it was only a passenger on that colorfully painted bus, and its relevance, its ability to touch and edify the reader, did not disappear when the bus drove on. Hesses brilliance continues to stand out because of his inalienable need to find the real beyond the conventional in experience, the moment out of time. His pilgrim spirit looked to the wisdom of the East and many followed his lead.

In a certain way, the present book, translated here into English for the first time, conveys Hesses essential qualities better than his novels do. This is because in these accounts, Hesse himself is the main character. As he travels, we see directly through his eyes rather than those of a fictional character. Inevitably in novels, perceptions are molded and forced by plot. The characters thoughts are driven by the authors plan. In Singapore Dream and Other Adventures, the writers pen is free of those constraints. We receive Hesses immediate impressions, and he does not sugarcoat. The only slight torsion and drive in these narratives come from the pleasure Hesse gets out of telling a story, expressing authentic experience in an apt and catchy way. He does not falsify, because he is inherently unable. In fact, we feel sympathy for the man, for we see that he is helplessly captivated by his experience. His absolute need of authenticity is something for which he often suffered in his life, was often cast into psychological depths. But it was also this inalienable faithfulness of his engagement with things that caused him to keep growing as a man and a writer. And it is that quality, combined with his undeniable gifts as an entertainer, that continues to draw us into his writings today.

In 1911, with a couple of successful novels already under his belt, Hesse was invited by a friend of his, the painter Hans Sturzenegger, to accompany him to Singapore to visit Sturzeneggers brother, who was running the family business there. Hesse said yes. It was to be a tour of the islands of the East Indies on the way to Singapore, and of the west coast of India on the way home. Hesse was all but predestined for this journey. His parents and grandparents, both maternal and paternal, had established missions in India to convert the heathen. His mothers father knew nine Indian languages. As a boy in his grandparental and parental households in Germany, Hesse found Indian artifacts and sacred textsas specimens, as pagan memorabilia. In the end it did not matter that his family looked down upon these things from righteous Christian heights. Hesses childhood world was pervaded by the aura of them. A seed was planted, even though it was not the one his family had intended. They wanted him to carry on the familys missionary tradition, but Hesse dropped out of his theological studies at the age of fourteen. In 1911 he was lured to the East on new grounds of his own.

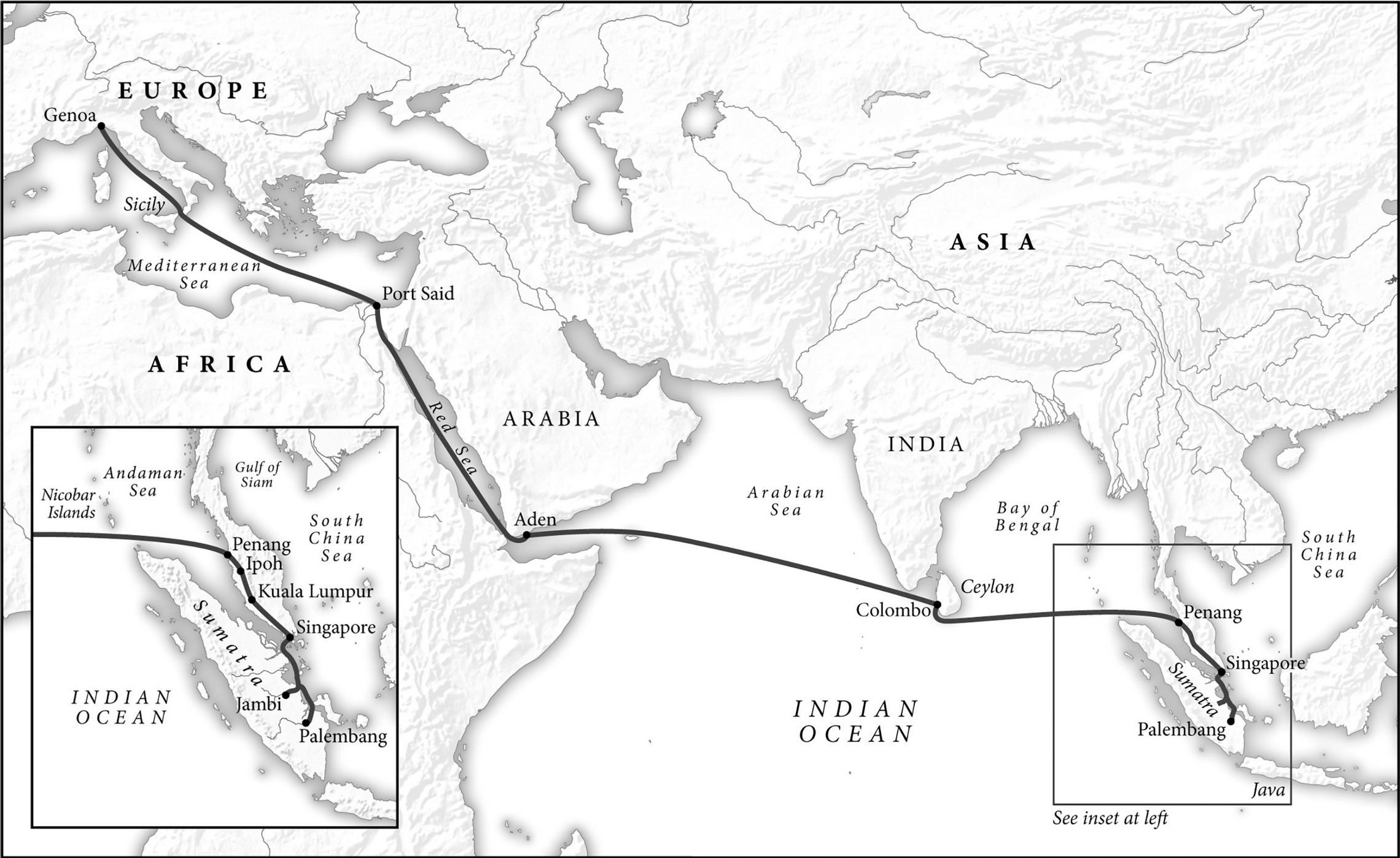

Hesse and Sturzenegger embarked on their journey in September of that year. They took the train to Genoa where they boarded a ship. They sailed between Sicily and the toe of Italy, east to Port Said, through the Suez Canal into the Red Sea, and into the Indian Ocean. They made landfall in Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) on September 23, in just over two weeks. Hesses missionary forebears, in the days before the Suez Canal opened in 1869, took over 150 days to reach India, enduring many hardships on the way (as we learn from Robert Aghion, at the end of this book). The voyage was much easier in 1911, but there were still long days and nights at sea in the torrid heat. Hesse complained that in one ship, his tiny inferno of a cabin lay right over the engine room; the floor scorched his feet and the porthole was the size of a pocket-watch crystal.