CHAPTER 8

Prenatal Care

Organized prenatal care in the United States was introduced largely by social reformers and nurses. In 1901, Mrs. William Lowell Putnam of the Boston Infant Social Service Department began a program of nurse visits to women enrolled in the home delivery service of the Boston Lying-in Hospital (Merkatz and colleagues, 1990). It was so successful that a prenatal clinic was established in 1911. In 1915, J. Whitridge Williams reviewed 10,000 consecutive deliveries at Johns Hopkins Hospital and concluded that 40 percent of 705 perinatal deaths could have been prevented by prenatal care. In 1954, Nicholas J. Eastman credited organized prenatal care with having "done more to save mothers' lives in our time than any other single factor" (Speert, 1980). In the 1960s, Dr. Jack Pritchard established a network of university-operated prenatal clinics located in the most underserved communities in Dallas County. In large part because of increased accessibility, currently more than 95 percent of medically indigent women delivering at Parkland Hospital receive prenatal care. Importantly and related, the perinatal mortality rate of women in this system is less than that of the United States overall.

OVERVIEW OF PRENATAL CARE

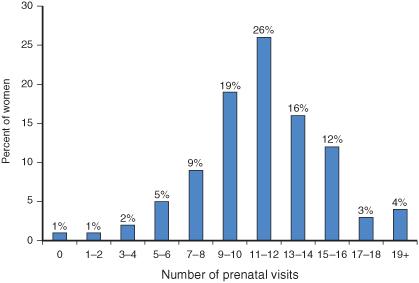

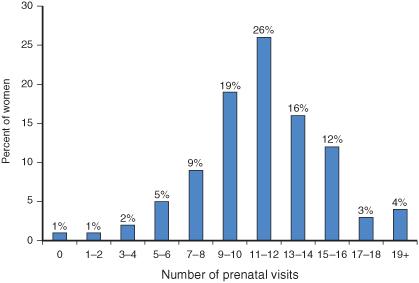

Almost a century after its introduction, prenatal care has become one of the most frequently used health services in the United States. In 2006, more than 4.2 million births were registered in the United States (Martin and associates, 2009). In 2001, there were approximately 50 million prenatal visits--the median was 12.3 visits per pregnancy--and as shown in , many women had 17 or more visits.

A new birth certificate form was introduced in 2003 and is now used by 19 states, with the remaining 31 states continuing to use the 1989 form. Unfortunately, data regarding the timing of prenatal care from these two systems are not comparable. For example, with the 1989 version that represents 2.2 million births, nearly 83 percent of women received first-trimester prenatal care in 2006. Conversely, those states using the 2003 version reported that only 69 percent of women received first-trimester care (Martin and associates, 2009). Although the difference is striking, it merely represents a change in reporting and is not a harbinger of diminished of prenatal care. Indeed, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008a), birth certificate data using the 1989 version show that more than 99 percent of women received some prenatal care in the third trimester.

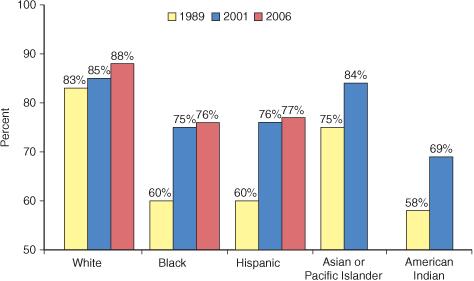

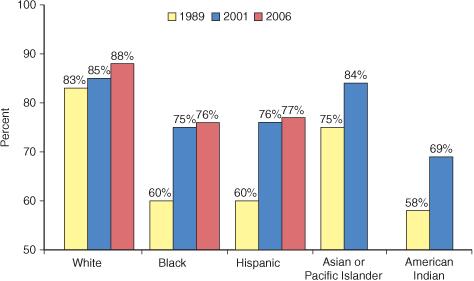

Since the early 1990s, the largest gains in timely prenatal care have been among minority groups. As shown in . Importantly, many of these complications are treatable.

Assessing Adequacy of Prenatal Care

Assessing Adequacy of Prenatal CareA commonly employed system for measuring prenatal care adequacy is the index of Kessner and colleagues (1973). As shown in , this Kessner Index incorporates three items from the birth certificate: length of gestation, timing of the first prenatal visit, and number of visits. It does not, however, measure the quality of care, nor does it consider the relative risk of complications for the mother. Still, the index remains a useful measure of prenatal care adequacy. Using this index, the National Center for Health Statistics concluded that 12 percent of American women who were delivered in 2000 received inadequate prenatal care (Martin and associates, 2002a).

FIGURE 8-1 Frequency distribution of the number of prenatal visits for the United States in 2001. (Adapted from Martin and associates, 2002b.)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000) analyzed birth certificate data for the years 1989 to 1997 and found that half of women with delayed or no prenatal care wanted to begin care earlier. Reasons for inadequate prenatal care varied by social and ethnic group, age, and method of payment. The most common reason cited was late identification of pregnancy by the patient. The second most commonly cited barrier was lack of money or insurance for such care. The third was inability to obtain an appointment.

Effectiveness of Prenatal Care

Effectiveness of Prenatal CarePrenatal care designed during the early 1900s was focused on lowering the extremely high maternal mortality rates. Such care undoubtedly contributed to the dramatic decline in maternal mortality rates from 690 per 100,000 births in 1920 to 50 per 100,000 by 1955 (Loudon, 1992). As discussed in (p. 5), the current low maternal mortality rate of approximately 8 per 100,000 is likely associated with the high utilization of prenatal care. Indeed, in a population-based study from North Carolina, Harper and co-workers (2003) found that the risk of pregnancy-related maternal death was decreased fivefold among recipients of prenatal care.

FIGURE 8-2 Percentage of women in the United States with prenatal care beginning in the first trimester by ethnicity in 1989, 2001, and 2006. (Adapted from Martin and associates, 2002b, 2009.)

There are other studies that attest to the efficacy of prenatal care. Herbst and associates (2003) found that no prenatal care was associated with more than a twofold increased risk of preterm birth. Schramm (1992) compared the costs and benefits of prenatal care in 1988 for more than 12,000 Medicaid patients in Missouri. For each $1 spent for prenatal care, there were estimated savings of $1.49 in newborn and postpartum costs. Vintzileos and colleagues (2002a) analyzed National Center for Health Statistics data for 1995 to 1997. They reported that women with prenatal care had an overall stillbirth rate of 2.7 per 1000 compared with 14.1 per 1000 for women without prenatal care--an adjusted relative risk of 3.3 for fetal death. Vintzileos and colleagues (2002b, 2003) later reported that prenatal care was associated with significantly lower rates of preterm births as well as neonatal death associated with several high-risk conditions that included placenta previa, fetal-growth restriction, and postterm pregnancy.

ORGANIZATION OF PRENATAL CARE

The essence of prenatal care is described by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2007) as: "A comprehensive antepartum care program involves a coordinated approach to medical care and psychosocial support that optimally begins before conception and extends throughout the antepartum period." This comprehensive program includes: (1) preconceptional care, (2) prompt diagnosis of pregnancy, (3) initial prenatal evaluation, and (4) follow-up prenatal visits.

Preconceptional Care

Preconceptional CareBecause health during pregnancy depends on health before pregnancy, preconceptional care should logically be an integral prelude to prenatal care. As discussed in detail in , a comprehensive preconceptional care program has the potential to assist women by reducing risks, promoting healthy lifestyles, and improving readiness for pregnancy.

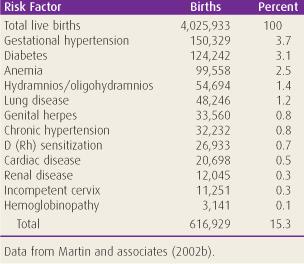

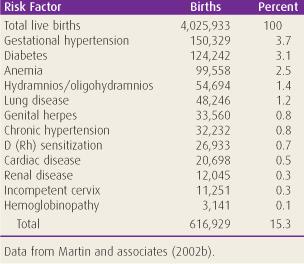

TABLE 8-1. Obstetrical and Medical Risk Factors Detected During Prenatal Care in the United States in 2001

Assessing Adequacy of Prenatal Care

Assessing Adequacy of Prenatal Care