Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Jeffrey S. Kamm

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.723.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016944045

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.848.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PREFACE

Indianapolis often gets a bad rap as being a bland food city. Located just down from the alpha city of Chicago and all its culinary delights, its easy to see why the Home of Wonderbread often is overlooked. Granted, much of this is self-inflicted, as many visitors can drive down mile after mile of automobile-oriented strip development and see the endless supply of chain restaurants serving up the same fare one can find in Sand Diego, California, or Bangor, Maine. This has not always been the case. For the past two years, I have had the privilege of writing articles for a history-oriented website in Indianapolis. My focus mainly has been places of leisure, such as restaurants, nightclubs, movie theaters and hotels. One thing I have noticed is that when I write about a long-standing local restaurant that is no longer with us, it brings out many comments and personal stories. People are drawn to unique experiences they have encountered over the years. These memories help define a sense of place and pride for the city in which they hail. People enjoy a unique dining experience despite what the modern world has programmed them to accept.

Indianapolis exists strictly by design. There was no navigable waterway that would have drawn settlers or any abundant natural resource to draw industry. The area was largely flat and swampy. In fact, the original Native Americans considered the area a common hunting ground for tribes and opted to settle in other areas. Shortly after achieving statehood, leaders desired a capital city that would be centrally located and chose the area at the convergence of the White River and Fall Creek. The states fathers chose renowned city planner Alexander Rolston to plot the land. Rolston was so enthused by the prospects of this made-from-scratch state capital that he reduced the original plan from four square miles to just one. The first New Years celebration was held in the Wyatt Tavern, a boardinghouse that provided meals in 1822. The population was fewer than two thousand. The fledgling city would limp along for the next twenty years.

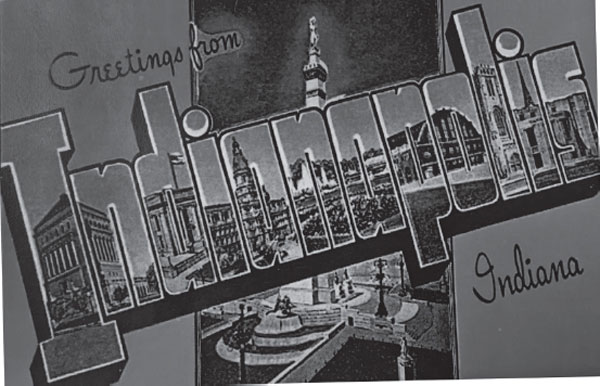

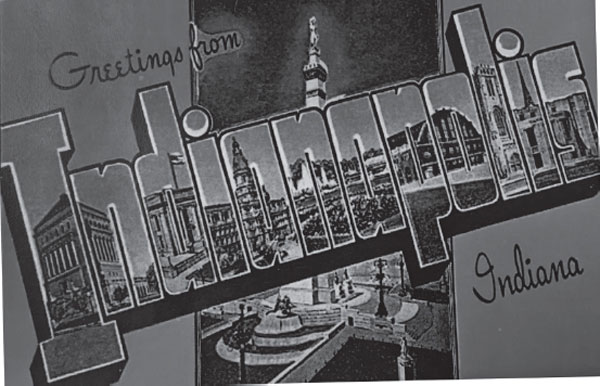

Welcome to Indianapolis! Landmarks on this postcard include the Indiana War Memorial, Federal Post Office and Courthouse, Marion County Courthouse (demolished), Garfield Sunken Gardens, Hinkle Fieldhouse, Scottish Rite Cathedral (Freemasons) and United States Naval Armory. Courtesy of Jeff Kamm.

This image of Monument Circle would predate 1925. None of the visible buildings is standing these days. The lavish English Hotel on the far left is considered one of the most notable architectural losses in the city. The building met its demise back in 1949 to make way for a rather bland J.C. Penney Store. That store closed in the early 1980s. Today, the building has been converted to offices. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The buildings in this shot of Washington Street looking west would date this photo between 1905 and 1908. L.S. Ayres is shown completed, but the massive Barnes and Thornburg Building has yet to be constructed. L.S. Ayres was the most lavish department store in Indianapolis and featured eight floors of retail and an elegant tearoom. In the 1950s, Ayres began constructing outlets in suburban shopping centers across the state. This led to a decline in the downtown store, which closed in 1992. No trace of L.S. Ayres remains today, as it was absorbed by the Macys chain. The massive Thomas building at mid-left was destroyed by a fire in 1973 that started in the neighboring Grant Building. Washington Street served as the major retail corridor in the city through the 1960s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

These panoramic shots were taken from atop the Lincoln Hotel at the intersection of Kentucky Avenue, Illinois Street and Washington Street. The Lincoln served the city for many years and became a part of the Sheraton chain of hotels in the 1950s. The hotels fortunes had turned by the 1960s as newer suburban hotels came into favor. The Lincoln closed in 1968. The building was imploded among much fanfare in 1973 to make way for Merchants Plaza. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

After a botched canal project that bankrupted the state, the city finally began to take off when the railroad came to town in 1847. Due to its strategic location, Indianapolis became a crossroads. The first Union Station was established here in 1853 serving all the lines converging on the city. The station was replaced in 1888 with the grand Romanesque structure that remains to this day. During this time, many hotels developed to serve different classes of travelers along Illinois Street. A strong saloon culture evolved.

By the 1920s, the automobile had begun to creep its way into the hearts of city residents, and Indianapolis served as a major manufacturing hub, rivaling even Detroit, prior to the Great Depression. During this time, a new concept of restaurant evolved. Cafeterias began popping up around the city. These restaurants featured a long counter where diners could make their selections of the items of the day. This allowed meals to be served in a quick and orderly fashion. This style of restaurant remains popular to this day. By the 1930s, another new concept had begun turning up: a restaurant where one could pull in and be served his meal in a car!

The Great Depression and food rationing in World War II limited the development of restaurants. By the 1950s, people felt liberated and were ready to celebrate their newfound wealth and prosperity. This was the heyday of the supper club. These were a one-stop shop for an evening of entertainment. You could arrive early, enjoy a lavish meal and then be entertained. These boozy and decadent rooms were often found in old Victorian houses lining North Meridian Street. While Mom and Dad had a nice evening out, the teenagers took to the streets, creating a strong cruising culture. Drive-in restaurants would vie for attention, some offering movies or live disc jockeys. Aside from this, the roadside diner was in its heyday, and many could be found on the highways coming into the city.

Next page