Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

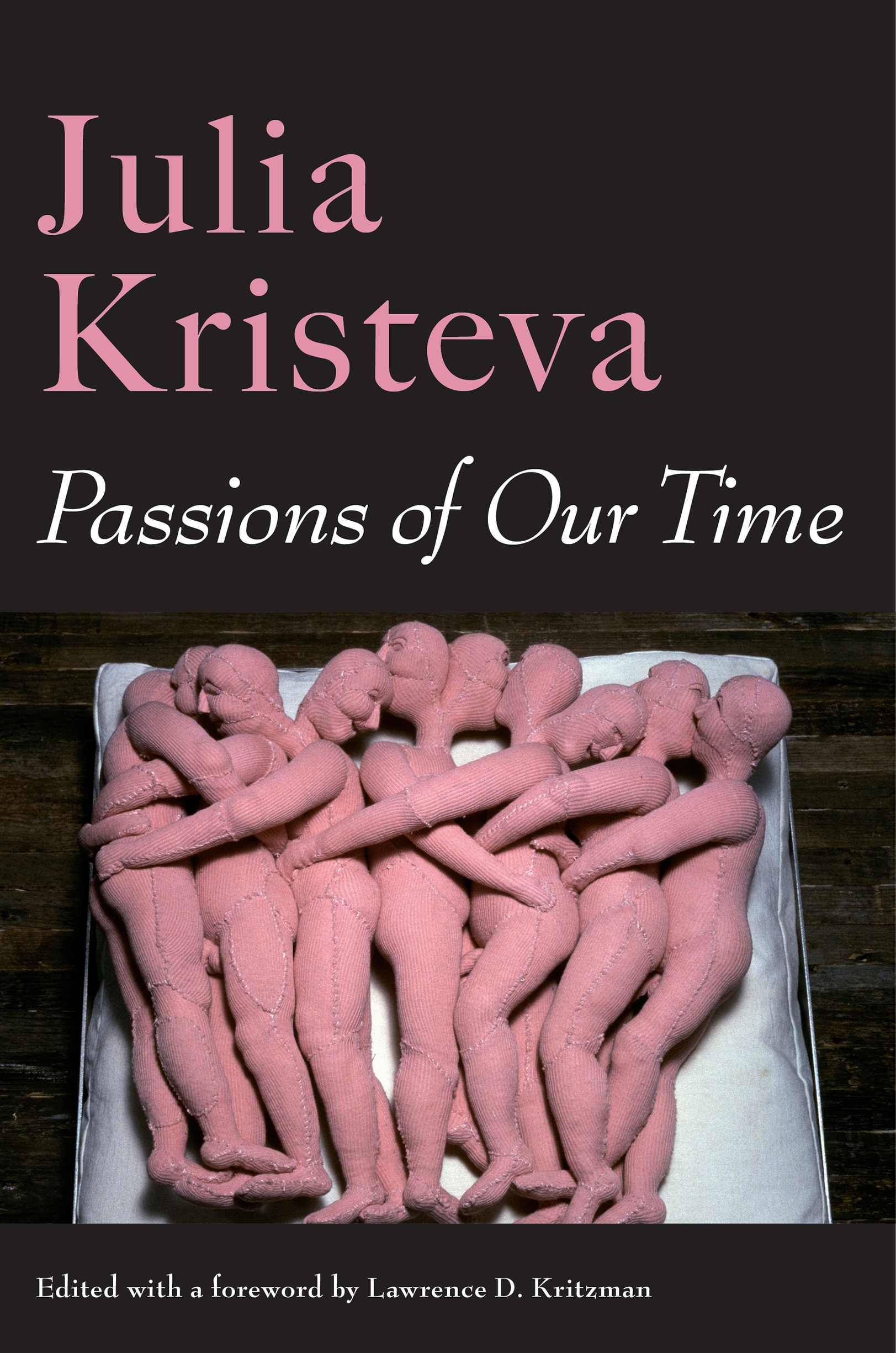

PASSIONS OF OUR TIME

EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES

EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES

A SERIES IN SOCIAL THOUGHT AND CULTURAL CRITICISM

Lawrence D. Kritzman, Editor

European Perspectives presents outstanding books by leading European thinkers. With both classic and contemporary works, the series aims to shape the major intellectual controversies of our day and to facilitate the tasks of historical understanding.

For a complete list of books in the series, see .

PASSIONS OF OUR TIME

JULIA KRISTEVA

EDITED WITH A FOREWORD BY LAWRENCE D. KRITZMAN

TRANSLATED BY CONSTANCE BORDE AND SHEILA MALOVANY-CHEVALLIER

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support for this book provided by Publishers Circle members Judith Ginsberg and Paul LeClerc.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Pulsions du temps copyright 2013 Librairie Arthme Fayard

French edition edited by David Uhrig with Christina Kkona

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54749-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kristeva, Julia, 1941 author.

Title: Passions of our time / Julia Kristeva; edited and foreword by Lawrence D. Kritzman; translated by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier.

Other titles: Original title: Pulsions du temps

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, 2018. | Series: European perspectives: a series in social thought and cultural criticism | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018007443 | ISBN 9780231171441 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Time. | TimePsychological aspects.

Classification: LCC BD638 .K75513 2018 | DDC 194dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018007443

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Julia Kushnirsky

Cover image: Louise Bourgeous, Seven in a Bed

CONTENTS

LAWRENCE D. KRITZMAN

LAWRENCE D. KRITZMAN

P assions of Our Time represents the work of an exemplary twenty-first century intellectual, Julia Kristeva, a true renaissance woman, a theoretical polymath whose many insights engage in political and social questions. This book takes us on a critical journey examining politics, philosophy, psychoanalysis, gender and sexuality, literary criticism, religion, and cultural critique. Earlier versions of many of the chapters in Passions of Our Time were previously published as articles, lectures, and book chapters. Kristevas principle concern is time in its broadest sense in the contemporary world. Her attempt is to show how time, in todays world, has become a closed phenomenon and lost some of its kinetic force through digitalized uniformity and hyperconnectivity. Kristeva shows how internal drives, in a Freudian sense, can reactivate the kinetic force of time within us and therefore valorize its singularity in a world that is plural and diverse.

In a first essay, one that functions as a theoretical allegory of her writerly vocation, she demonstrates how her future was overdetermined by an activity she engaged in at a childrens festival in Bulgariathe festival of the Slavic alphabet (the holiday of the Cyrillic letters). This symbolic investment constituted the letter, her engagement with language as translation, by allowing it to become a sort of fetishistic object in which writing was the medicine that planted the seeds of her intellectual journey and cured her of the ills of living under communism.

As in her previous work, Kristeva engages in psychoanalytic speculation, but she never does so in a dogmatic manner, whereby the analyst would take on the position of an all-knowing subject. Drawing on Freud, Lacan, feminism, and theories of the maternal, Kristeva highlights the importance of psychoanalysis in todays world. As she sees it, psychoanalysis functions as a bridge between humankind and civilization, an activity that enables the unbuttoning of the enigma of human existence. To be sure, her engagement with this heuristic process does not allow the human subject to conform to social norms. Instead it enables the subject to come into contact with the singular freedom that gives birth to creativity and the escapades of the imagination.

Throughout, Kristeva examines the infelicitous consequences of the acceleration of time. What Kristeva perceives as the paradoxical result of this acceleration of time is what she refers to as a deep nihilistic crisis in which diversity has given rise to new authoritarian discourses, new anti-Semitisms, and Islamophobia. This crisis was produced by the failure to recognize alterity (Every I is another) and the refusal to let the other speak. As Kristeva has previously shown in her study of Hannah Arendt, secularization produced the eradication of Jewish difference into the generic man. In opposition to a cult of identity and the corrosive force of hate produced in a self-contained environment, Kristeva proposes a more felicitous reciprocating questioning that provides a model for living together as a plural phenomenon. The loosening of borders through the activity of globalization has allowed for multicultural cross-fertilization. Yet at the same time it has allowed for the resurgence of abject nationalism because of the infelicitous clichs proliferated by identity politics articulated in a self-contained hermetic world.

At the core of this nihilistic crisis is the failure, metaphorically speaking, of what she terms the need to believe. This phenomenon does not call for a religious revival capable of producing a dangerous fundamentalism. Kristeva equates the need to believe with Freud, who secularized religion and used it as a trope for the egos drive to create meaning and its desire for knowledge.

The acceleration of time in the digital age has created an identity crisis for both the individual and the nation. The dissolution of a community of differences has had a negative impact on reciprocal trust. To be sure, Kristeva does not espouse the idea that the universe is one, but puts forth the concept of a multiverse open to the fractures of time. This dialogic approach gives new hope to the melancholia produced in the mechanistically closed temporal space of digital technology. The creation of a multiverse allows for the mobilization of creativity as it is libidinally enacted; it therefore allows for the transcendence of dogmatic political ideologies and the authority that technology imposes and regulates. As in the case of the latter, the Internet, that messianic messenger of the contemporary world, forecloses on creativity and imposes the fabricated images of human experience. This foreclosure on creativity functions as a form of political control marked as a new human narrative that undercuts the possibilities of difference. Technological policing closes off the creativity produced in the unexpected fractures of time. The response to new technologies can only be counterbalanced by an enlightened inner life. But this phenomenon, according to Kristeva, can only be realized by giving oneself to another as in the care of the mother for the child and the primary identification of the boy with the father. Accordingly, one is able to live by investing in the other and the subsequent creation of reciprocal links.