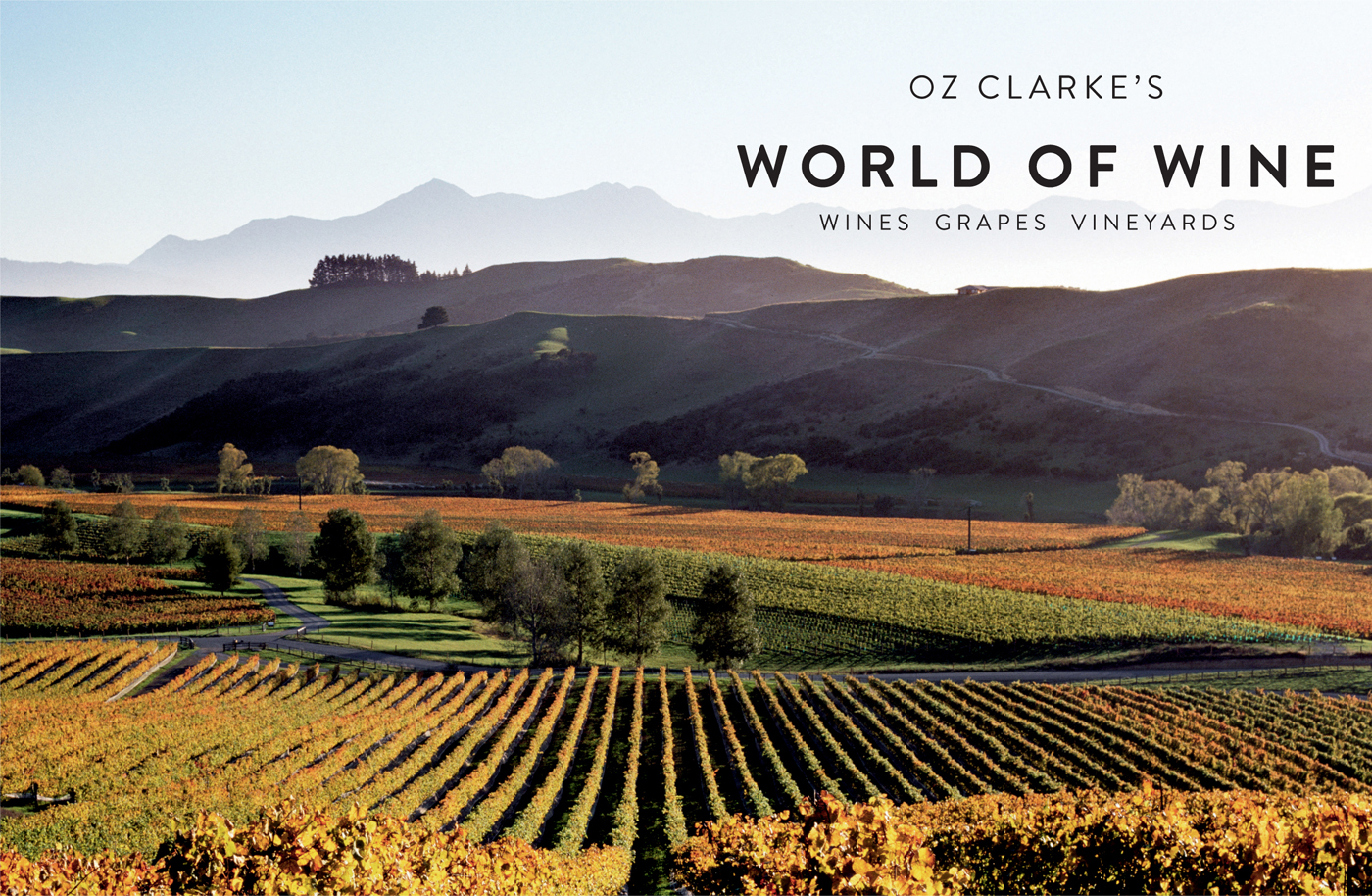

OZ CLARKES

WORLD OF WINE

WINES GRAPES VINEYARDS

Clayridge Vineyard to Cloudy Bay Barracks Vineyard in the Upper Omaka Valley, Marlborough, New Zealand.

Contents

Sorting harvested Merlot grapes in the vineyard of Chteau Haut-Brion, Pessac-Lognan, Bordeaux, France.

About Wine

S ometimes I stop and ask myself: when was the last time I had a glass of bad wine? Not wine that is out of condition, or corked wine, or wine that Ive left hanging around in the kitchen for too long but poor, stale, badly made, unattractive wine? And unless Ive been extremely unlucky in the previous month or so, I wont be able to remember. The standard of basic winemaking is now so high that a wine drinker need never taste a wine that is not at very least clean, honest and drinkable. It wasnt like that a generation ago. And then, I sometimes idly try to work out how many different grape varieties from how many different wine regions Ive tried during a typical wine-tasters week. At a recent tasting I counted the number of grape varieties contributing to an exciting array of wines. Seventy different grape varieties, from places as familiar as France and Italy and Spain, and as far flung as Tasmania and Brazil, New York and Bolivia. And it wasnt like that a generation ago, either.

For me the thrilling thing about this modern world is that we now have choice endless choice that gets bigger every year. And with choice, comes excitement, challenge, but also confusion. But thats why this book is here to help you: to make sense of this cornucopia of flavours and delights that extends from the most famous and expensive wines of Bordeaux and Burgundy down to the first nervous offerings of new vineyards from unsung valleys.

We, as wine drinkers, should take some credit for this transformation. If we were not prepared to try new things, to take a bit of risk with unknown areas and unknown grapes winemakers would neither bother to resurrect old areas and plant new ones, nor bother to spread their activities beyond a few popular grape varieties. If we werent prepared to be adventurous, wine companies would simply flood us with a sea of Chardonnay, Sauvignon, Cabernet, Merlot and Shiraz/Syrah, gaudy labels and fantasy names bedecking wines that make no attempt to taste different or individual. But you and I would be missing out on so much.

We are in the midst of a revolution in wine that is bringing together the best of the new and the old. Traditionalists are realizing that maybe the old ways are not always the best, that they can learn something from the brash younger generation. And the modernists are quietly laying aside their reliance on cultured yeasts, scientific formulae and refrigerated stainless steel tanks, and listening with respect to the old farmers with their gnarled vines, and their quiet unhurried ways of letting a wine make itself as it will. Yet, with all this hectic change, the eternal truths of what makes wine good and special have never been more evident. Every good winemaker knows that the final limiting factor on wine quality is the quality of the grapes. And every winemaker knows that some regions grow better grapes than others, some areas within those regions are more suitable, some small patches of the very same field are better than others and some growers care more about their work and will always produce the finest fruit. And I unashamedly admit that I am more excited by the vineyard, by natures effect on the final flavour of wine, than I am by a winery, however full of state of art gadgets it may be.

If Im in Cte-Rtie, I want to climb to the highest point on the slope from whose grapes the juice always runs blackest and sweetest. I want to feel the poor stony soil crumble beneath my feet and touch the twisted, tortured trunk of the vine which each year struggles to survive on this barren slope and ripen its tiny crop. If Im in Margaux, I want to tread the warm, well-drained gravel outcrops and then step off into the sullen clay swamps nearby and, with this single step, Ill know why the gravel-grown grapes are precious and the clay-clogged ones are not. I want to see the Andes water gushing down into the fertile vineyards of Chiles Maipo Valley. I want to feel the howling mists chill me to the bone in Californias Carneros, and then feel the warm winds of New Zealands Marlborough tugging at my hair. I want it all to make sense.

And I want to take you to the oldest wine regions on earth and the newest. I want to discuss the most common grape varieties and the rarest. I want to talk about styles of wine that have hardly changed for 8,000 years, and about styles that seem to have been invented only yesterday. Fashion does play a big part in wine. A generation ago we lauded the rich, heady exotic Chardonnays of Australias Hunter Valley or Californias Napa. Now we crave the savoury, lean offerings from Australias Yarra Valley or Californias Sonoma Coast. A generation ago we praised the light and often feeble attempts to ape Burgundy which marked out the early Pinot Noirs of Oregon and New Zealand. Now we cheer their self-confident and definitely non-Burgundian Pinot Noirs with far greater conviction.

In this age when change has come faster than ever before in the world of wine, it is certain that within the decade some vineyards now in decline will be fired by a new confidence and popularity; others now considered so chic will be struggling in the tough real world as their first flush of fame dissolves; and yet others, at this moment mere pastureland or rocky mountainside, will become flourishing vineyards producing wines whose flavours may be entirely different to anything yet achieved on this planet. And all of these I want to share with you in this book.

China is now a serious wine-producing nation. These vineyards are near Ximangtong village in the LanCang River Valley, Yunnan Province. They are way up in the Himalayan foothills and despite serious challenges with infrastructure, Yunnan could prove to be Chinas best vineyard region yet.

The Story of Wine

Wine is as old as civilization probably older while the vine itself is rooted deeply in pre-history. There was at least one species, Vitis sezannesis, growing in Tertiary time just a mere 60 million years ago. I dont expect that sezannesis ever turned into wine not on purpose, anyway, but aeons later its descendant Vitis silvestris surely did (and still does in Bosnia-Herzegovina, where it is called the Iosnica) and by the Quaternary era around 8000BC the European vine, Vitis vinifera (from which nearly all the worlds wines are now made), had come on the scene.

The metamorphosis of grape into wine was almost certainly a happy accident. Imagine Stone Age people storing their hedgerow harvest of wild grapes, Vitis silvestris, in a rocky hollow some of the grapes squash, juice oozes out and, in a flush of autumn sunshine, begins to ferment. The result however unpalatable to todays tutored taste must have cheered the chill of cave-dwelling and provided a few much-needed laughs at the onset of pre-central heating winter. Similarly, in the houses of ancient Persia, Mesopotamia, Armenia, Babylon the occasional jars of raisined grapes, ready for winter eating, would surely have begun unexpectedly to bubble and froth and magic themselves into a sweet, heady drink. From such haphazard beginnings, wine evolved into an adjunct of civilization: the Georgians were probably at it around 6000BC. Ancient paintings and sculptures show that both Egypt and China were making and drinking it around 3000BC, but it was really the Greeks who first developed viticulture on a commercial scale and turned vinification into a craft. Their wines tended to be so richly concentrated that they were normally drunk diluted: two parts wine to five of water. And they were syrupy sweet yet with a sting of salt or a reek of resin, cadged from casks washed out in sea-water or from amphoras lined with pitch-pine. Through their trading travels, the Greeks spread their vine-and-wine knowledge around the Mediterranean and were particularly influential in Italy to the benefit of the worlds wine-drinkers ever since.

Next page