One Year Off

Leaving It All Behind for A Round-the-World Journey With Our Children

David Elliot Cohen

Includes a new afterword, Where Are We Now?

And with photographs by Devyani Kamdar and David Elliot Cohen

Contents

Praise for One Year Off

The book that launched a thousand trips!

Refreshingly frank. Travel + Leisure

Honest, reflective, and often uproariously funny. San Francisco Chronicle

Humorous and gripping. Publishers Weekly

Witty, honest and amazingly sane. Chicago Tribune

A landmark in travel literature. Boston Herald

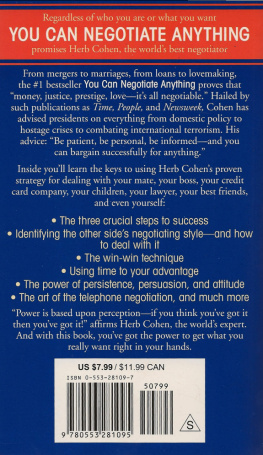

Starting out as the kind of innocents abroad who cause natives to snicker, [the Cohens] eventually make the tricky transition from tourists to travelers, and even if would never want to do this yourself, they are charming travel companions. People

Cohen proves to be a very capable writer, filling his narrative with interesting and amusing accounts. The Christian Science Monitor

Prologue

Some people have resolute ideas about how their lives should unfold. As adolescents or young adults, they set goals and chart courses. When they encounter obstacles, they surmount them and move forward. If they stray from their preordained path, they always find their way back. For better or worse, Ive never been one of those people. Maybe Ive never found my true mtier. More likely, I just have a short attention span. But whatever it is, life has always seemed far more interesting when there is a healthy element of serendipity involved.

My young adulthood was shaped by this instinct for adventure. An otherwise lackluster career at Yale was punctuated by two unusual summer jobsone as an assistant to a member of the British Parliament and another as an intern at the American embassy in Freetown, Sierra Leone, West Africa. At the time, I didnt consider these positions to be great career opportunities. I just thought that listening to constituents problems in a dreary Midlands housing project or touring an African bush town were great ways to sample the world.

When I graduated from college, I didnt have the slightest idea what sort of career I wanted. If someone had handed me an open air ticket along with my diploma, I would have gladly jetted off to Tibet or Timbuktu. But that didnt happen. Instead I ran into my father, who with the very best intention, gently prodded me into law school. (Even if you dont become an attorney, its great mental training.) So with a vague sense of dread, I trundled off to law school. I still remember sitting in a huge classroom on the first day of school with 150 or so eager novitiates. The deana noted contracts scholarstrutted across the stage like a puffed-up peacock and boomed, Were going to change everything about the way you think!

My first reaction to that was, Not if I can help it, buddy. And, of course, that set the stage for a truly gruesome year, where I proved two theories conclusively: 1) the first year of law school isnt the preferred venue for contrarian thinking, and 2) you cant learn torts and civil procedure through osmosis. No one was sorry to see me go.

After that, I served an undistinguished stint as a sales clerk in a Pittsburgh bookstore. I thought it was a great job because I got to spend most of my time browsing the inventory and chatting with customers. But eventually, my parents intervened again and prevailed upon me to try something more ambitious. So I bought a copy of The New York Times and scanned the want ads. The very first notice that caught my eye called for a publicity director at a small Manhattan-based photography-book-publishing house called Aperture. Aperture published work by some of the worlds finest art photographersgiants such as Robert Frank, Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange, Edward Steiglitz, and Minor White. I always admired Apertures lavish publications when they turned up at the bookstore, and more importantly, I thought it would be exciting to live in New York for a while. I applied for the position and got it.

Six months later, the talented martinet who ran the place fired me for unconscionable indolence and general insubordination. In retrospect, Id have to say he was fully justified on both counts. I believe the breaking point came when he spent half an hour expounding his philosophy of life and art to me, and I replied, But thats just Platos Myth of the Cave repackaged. No one likes a smart-ass, and I quickly found myself living in the middle of Manhattan with no job, no income, no prospects, and roughly four weeks savings.

You might think this situation would have humiliated and frightened me. (It certainly would now.) But at the time, I wasnt all that worried. Ill be the first to admit that I didnt take full advantage of all the educational opportunities offered at Yale, but I did learn the most important thing they taught therebaseless self-confidence. Its a lesson that cant be underestimated. My classmates and I left our graduation ceremony on Yales Old Campus fully convinced that we were incapable of anything short of rousing success. In fact, the joke amongst the underachieving set was that if you did manage to graduate from Yale (which is almost a given), you could never become a bummerely an eccentric. Over time, lifes vicissitudes eventually convinced nearly all of us that we could fail as well as the next guy. But at twenty-three, I was still pretty well inoculated with Ivy League bravado and roundly sure that if I got fired, it was only because the boss was a jerk, and something better would turn up the following week.

In this case, it did. When I had $200 left in my bank account and a $292 rent payment due, I received a call from Guy Coopera totally hip British picture editor who lived in Harlem and played the guitar like Mark Knopfler. Guys wife, Lela, hailed from my hometown of Erie, Pennsylvania, and I used to date her sister. Anyway, Guy said he was leaving his position at a small, prestigious photo news agency called Contact Press Images in order to become associate picture editor of Newsweek. Guys bossa roguish, charismatic photo-guru named Robert Pledgetold Guy to find his own replacement before he left. So Guy ransacked his Rolodex looking for someone, anyone, vaguely qualified for the job. Fortunately, Cohen is near the beginning of the alphabet.

I hoped that Pledge (everyone called him just Pledge) wouldnt hold my recent dismissal against me, but he couldnt have cared less about the blots on my copybook. Pledge worked from the gut, and he figured that we would get along well and Id work like a campesino if I liked what I was doing. In turn, I saw the blustering, bearded forty-year-old Frenchman as a kindred spirit, and I admired his panache. Pledge worked when he wanted towhich was often all night. He dressed like a slob. He turned down lucrative jobs because he didnt like the people offering them. And without benefit of any discernible management skills, he commanded a ragtag band of ten highly talented, fiercely loyal photojournalists, who roamed the earth covering stories in the name of truth and justice.

For a twenty-three-year-old kid in search of excitement, Contact Press Images was the best possible place to land. I earned a subsistence wage, but I scarcely noticed because every day was a new adventure and every breaking news story seemed to concern me personally. I loved the little yellow boxes full of slides (we called them transparencies) that were couriered back to New York from Irian Jaya and El Salvador. I loved the adrenaline rush when we landed a scoop or made a magazine deadline by minutes (which, given Pledges management style, was fairly routine). And I secretly relished the late night phone calls when Pledge would growl in his throaty, accented English, The Shah of Irans been overthrown. Find David Burnett in Manila and get him to Teheran.