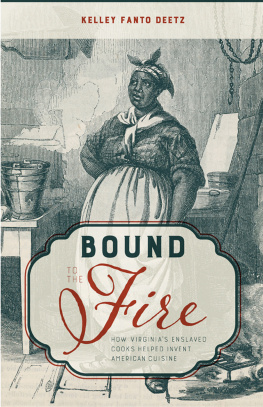

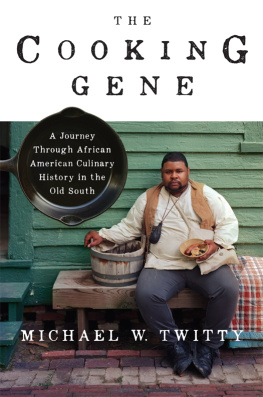

BOUND TO THE FIRE

BOUND

TO THE FIRE

How Virginias

Enslaved Cooks

Helped Invent

American Cuisine

KELLEY FANTO DEETZ

Copyright 2017 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Deetz, Kelley Fanto, author.

Title: Bound to the fire : how Virginias enslaved cooks helped invent American cuisine / Kelley Fanto Deetz.

Description: Lexington, Kentucky : The University Press of Kentucky, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017029779| ISBN 9780813174730 (hardcover : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780813174747 (PDF) | ISBN 9780813174754 (ePub)

Subjects: LCSH: SlavesVirginiaSocial life and customs. | SlavesVirginiaSocial conditions. | African American cookingHistory. | Cooking, AmericanHistory. | African AmericansFoodVirginiaHistory. | African American cooksVirginiaHistory. | African American cooksVirginiaBiography. | SlavesVirginiaBiography. | Plantation lifeVirginiaHistory. | VirginiaRace relationsHistory.

Classification: LCC E445.V8 D44 2017 | DDC 641.59/296073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017029779

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

In loving and respectful memory of Jody Kelley Deetz, VeVe Anastasia Clark, James Fanto Deetz, and the ancestors

CONTENTS

Introduction

IN MYTH

Cecily Hemphill wakes early on a Saturday to make her girls breakfast. Looking into her cabinets, she realizes she is out of pancake mix and runs down to the Safeway on Lakeshore Avenue in Oakland, California. Meanwhile, Jim Keller is in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, plotting his menu for tomorrows Sunday brunch. He too heads to the local grocery to shop. In Boston, Shann Whynot-Young runs to the corner market to fetch some syrup for the family. Down in Tampa, Florida, Jennifer Hercules is staring at the syrups in the grocery aisle and reaches for a familiar and affordable choice. All four people choose Aunt Jemima to help them make a quick and reliable meal. Something about her smiling face ignites an instinctual response from consumers. What is it about this name, this face, and, specifically, the lure of the brand that causes people to buy this product? Is it simply the low price and the familiarity, or is it the four centuries of marketing black cooks as trustworthy kitchen help? Aunt Jemima is the iconic enslaved cook. But who does she represent, and what do we know about those who actually cooked for their oppressors?

In American popular culture, enslaved cooks have been either portrayed as Uncle Toms or romanticized by the popular image of Aunt Jemima.1 As one of the most prevalent and lasting images of slavery, the black cook is found in everything from grocery ads to cartoons, and as a result, American consumers have become accustomed to this imagery. Having the picture of Rastus on a box of Cream of Wheat or Aunt Jemima pancake mix in your cupboard leads to an uninformed yet intimate familiarity with these icons. The idea of the nonfictional black cook has become ingrained in American domestic culture, sitting alongside canned goods on grocery shelves and at breakfast tables, without questioning the reality of their position in American history. Through systematic primary research, this book uncovers the centrality of the cooks role both in the kitchen and in the larger plantation community. Who were these men and women who were forced to cook for those who enslaved them?

This book is an interdisciplinary study that focuses on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century enslaved plantation cooks in Virginia and explores the influence of their legacy on twentieth- and twenty-first-century American memory. To render their significance in American cultural and social history, this work draws on archaeological collections, cookbooks, plantation records, material culture, folklore, and cultural landscape studies.

Plantation cooks were highly skilled, trained, and professional. They created meals that made Virginia famous for its cuisine and hospitality, and they were at the core of Virginias domesticity and culinary pride, as well as at the heart of the plantation community. Enslaved cooks existed between two worldsliving and laboring in their enslavers homes, under their watchful eyes, yet belonging to the larger enslaved community who resided in field quarters away from the main house. These cooks occupied this liminal space and used this axis to manipulate their existence in the brutal culture of chattel slavery.

The legacy of enslaved cooks, or of house slaves generally, is riddled with myths rooted in misunderstandings of the past. Fictional sources such as the Willie Lynch Letter, which illustrates a strict antagonistic division between light-skinned house slaves and dark-skinned field slaves, have created a hysteria of false proofs that feed the hunger for answers about the past and continue to mislead eager-minded folks to sources that are not, in fact, real. As a result, these enslaved domestics are depicted as docile, loyal slaves who had little connection to the larger enslaved population. This book unveils the richness of the archives and other sources related to those who worked inside plantation kitchens and offers a nuanced look at an aspect of history that gains as much from myth as it does from reality. It examines how we choose to remember the past, versus what the evidence suggests. This work engages in direct conversation with the folklore surrounding the loyal, happy house slave and presents a counternarrative to our historical imaginations.

The archaeological and historical records demonstrate the centrality of the cooks role in the plantation community, and their material culture shows how these cooks created a black landscape within a white world and were able to share this unique space with the larger enslaved population. Their voices are often hidden in the recipes recorded in handwritten cookbooks, in the archaeological remnants of their material world, in oral histories, and in some documented slave narratives. Their labor constituted only a portion of their lives, while their cultural influence is firmly demonstrated by the retention of African foodways in American cuisine. Some of their personal stories provide compelling evidence of the complicated relationships that existed in the social world of southern plantations. Enslaved domestics used their skills to manipulate their enslavers. They were subversive and intentional and remained anchored to the larger enslaved community, despite their physical location within the big house.

Next page