this first English translation

supported by a grant from

Figure Foundation

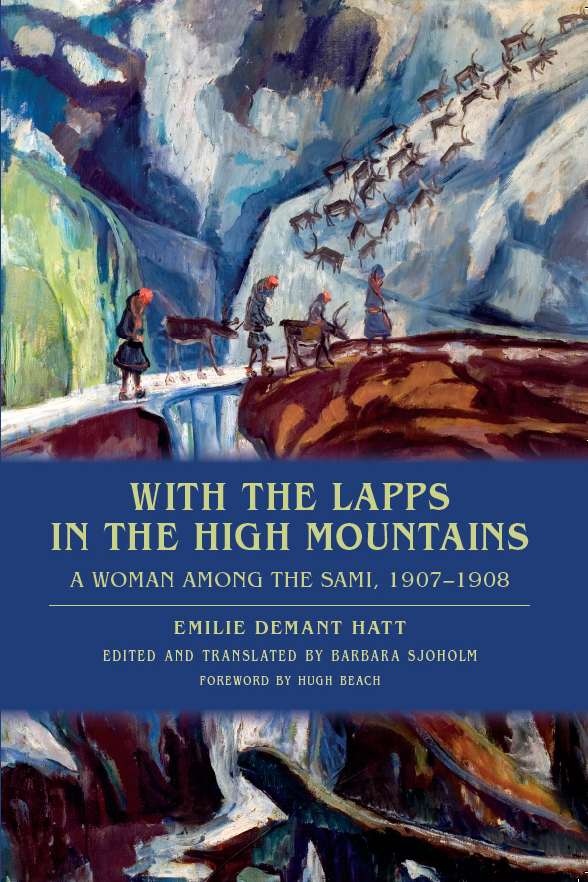

With the Lapps in the High Mountains

A Woman among the Sami, 19071908

EMILIE DEMANT HATT

Edited and translated by Barbara Sjoholm

THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN PRESS

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London wc2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Originally published in Danish as Med lapperne i hjfjeldet,

copyright 1913 by Emilie Demant Hatt

Introduction and translation copyright 2013 by Barbara Sjoholm

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or

a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except

in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hatt, Emilie Demant, 1873-1958.

[Med Lapperne i hjfjeldet. English]

With the Lapps in the high mountains : a woman among the Sami,

1907-1908 / Emilie Demant Hatt ; edited and translated by Barbara Sjoholm.

p. cm.

Originally published in Sweden as Med lapperne i hojfjeldet, copyright 1913.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-299-29234-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-299-29233-1 (e-book)

1. Sami (European people)Sweden. 2. Hatt, Emilie Demant, 1873-1958Travel.

3. LaplandDescription and travel. I. Sjoholm, Barbara, 1950- II. Title.

DL641.L35H3818 2013

305.894570485dc23

2012032682

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following publications, which first

published excerpts from With the Lapps in the High Mountains: Two Lines

(spring 2007), Antioch Review (spring 2008), Orion Magazine (July 2008,

web edition), and Natural Bridges (fall 2008).

Contents

With the Lapps in the High Mountains

Foreword

No one wishing to know anything about the Sami reindeer herding people of northern Fennoscandia can fail to encounter the name of Emilie Demant Hatt, a name forever associated with that of Johan Turi and his book Muitalus smiid birra. Muitalus appeared in English in 1931 as Turis Book of Lappland, the first book by a Sami author, but it is also very much Emilies book. She was its original translator and editor, as well as its promoter. As a young person growing up in America, I, like so many others, fell under its spell, and it fueled my dream of joining the reindeer herders. Remarkably, youthful dreams often do come true (perhaps because they are so many!), and I have had the pleasure to spend many years living with Sami herders in northern Sweden and in time to study their changing way of life as a professional anthropologist.

I encountered Emilie a second time when reading With the Lapps in the High Mountains, first published in 1913, but by then I had already spent some years with the herders myself, and my relation to it was therefore unlike that of so many others. These circumstances made this book all the more special to me, for I became amazed not so much by the material I read about the Sami, but rather by the kindred soul who had seen things so sharply and described them so lovingly. Yes, the book contains much of ethnographic value and provides a historic snapshot to academicians, but more than that, it is a riveting story filled with personal adventure and learning and yet entirely free of pretentiousness. In Emilies hands the Sami she meets come to life as human persons and are not simply objects of study or informants. Ironically, it is probably her lack of contemporary academic anthropological training, which frees her account from the contrivances of social theory of the times and concepts of the evolution of superior races, that makes her story timeless and brings it so much in line with the best of so-called postmodern anthropology.

It is often the simplest things that bring us together across the years. How well I appreciate her account of seeking relief from an overly smoke-filled tent by opening a makeshift vent hole in the tent cloth, lying with face turned outward to clear the eyes and gasp for fresh air, only to be forced in again soon by the cold. There is hardly a page that does not instill in me a sense of familiarity rather than exoticism, and I feel I know her herding friends rather well through many of the characteristics I have encountered among my own. This is not a communality she has spun in me simply through the similarities of our experiences; I think it is basically a matter of tone. She tells things as they are; she makes no attempt to be an observing scientist fly on the wall, but is an active agent and companion in the life of her hosts; she is a humanist. Most importantly, she did not set herself apart but wished to live among the Sami she visited as one of them, to learn from them and to pitch in with the work wherever she could.

With the Lapps is intimately related to Turis book about the Sami, but it is also entirely different. This is Emilies own account of her travels with the reindeer herding nomads of northern Sweden. Thanks to Barbara Sjoholm it now appears for the first time in English translation. While Turis book attained relatively swift international acclaim, With the Lapps has remained a little known gem. Assuredly it did stimulate a couple of past generations of Scan-dinavians to learn about the Sami and some perhaps to visit Spmi, but even for its limited readership the book has been out of print for decades. For a long time now it has held a place mainly in the hearts of scholars interested in the Sami and the north.

Barbara Sjoholm complements her translation with a biographical introduction. I find this facet of Sjoholms work every bit as meritorious as the translation itself. She has brought Emilie to life in all her complexity and freed her at last from the grudging fetters that have continually surrounded the importance of her contributions. To achieve her goals, Emilie had to negotiate them constantly with those of other strong-willed partners and benefactors. She was under pressure, for example, to bend the thrust of her work to substantiate the theoretical standpoint of her publisher, Hjalmar Lundbohm, regarding the proper education for Sami children. She must have been a superb diplomat, for in the end she always did as she wanted while maintaining good favor and respect.

Moreover, it cannot be denied that Emilies sizeable contributions to the spread of knowledge about and sympathy for Sami lifeways and culture, along with her appreciation of Sami people as equals to any others, has often been belittled by assertions of Sami cultural nationalism that occasionally have been misdirected. There are those who feel that Emilies light cannot shine too brightly lest it diminish the glow of Johan Turis as the first Sami author. She has therefore at times been portrayed as little more than a maid in his service to cook and wash while he wrote. Sjoholms exhaustive research through Emilies personal correspondence and that of those with whom she communicated reveals the many layers of Emilie and Johans intense relationship and her essential part in the course of forming