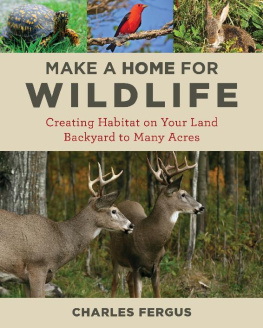

Make a Home for

Wildlife

Creating Habitat on Your Land Backyard to Many Acres

Charles Fergus

Stackpole

Books

Guilford, Connecticut

This book is dedicated to the women and men who today are creating and advocating for the habitats that wildlife needs to survive. Some of these people are landowners. Others have made conservation their lifes work and are employed by state and federal agencies, colleges and universities, and nonprofit organizations. They give wildlife a voice in todays world and teach us how to nurture the wild creatures whose continued presence makes this land a fascinating and wondrous place to live.

Published by Stackpole Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

800-462-6420

Copyright 2019 by Charles Fergus

Photographs by the author unless otherwise credited

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fergus, Charles, author.

Title: Make a home for wildlife : creating habitat on your land : backyard to many acres / Charles Fergus.

Description: Guilford, Connecticut : Stackpole Books, [2019] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018040811 (print) | LCCN 2018045810 (ebook) | ISBN 9780811767606 (e-book) | ISBN 9780811737722 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Wildlife habitat improvementEast (U.S.) | Habitat (Ecology)East (U.S.)

Classification: LCC QL84.2 (ebook) | LCC QL84.2 .F47 2019 (print) | DDC 577.0974dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018040811

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

You Can Make a Difference

On a bright summer day, I stood quietly at the woods edge and looked out on the two-acre field we call the Upper Meadow.

Orange hawkweed and yellow hawkweed, white daisies, red clover, and yellow buttercups spangled the fields lush greenery. (From violets and wild strawberries in May to goldenrod and New England asters in September, theres always something blooming in the Upper Meadow.) The slick, blade-like leaves of milkweed reflected light from the sky; unopened hot-pink flower clusters dangled from the plants tall stalks. Hawthorn shrubs and apple trees stood above the lower plants, their branches dotted with still-green fruit.

I raised my binoculars and scanned the field. Winks of tan, orange, white, and pale blue came from butterflies wings. A blue-green dragonfly hovered, then darted sideways to snatch a smaller insect out of the air. In the past, Ive spotted deer, wild turkeys, foxes, coyotes, and bears in the Upper Meadow, but none of those large animals were present that day.

The Upper Meadow at the Butternut Farm in northern Vermont, kept as old field habitat through periodic mowing. Burke Mountain stands in the distance.

Lowering my binoculars, I looked at those verdant acres. It wasnt hard to imagine meadow voles down at ground level, scuttling along on narrow runways through the weeds and grass, pausing and using their teeth to snip the plants stems and gain access to the upper, more succulent leaves and seed heads. I pictured field sparrows sitting on nests built on the ground, or attached to low blackberry canes, patiently incubating eggs or bringing insects to feed their growing nestlings. Caterpillars nibbling on vegetation. Spiders catching flies. Frogs and toads snapping up beetles and crickets. Shrews hunting earthworms. Weasels chasing mice.

I took a few steps into the open on a path I keep mowed along the fields upper edge. I glimpsed a sudden movement to my right: A hawk launched itself out of a tree, flapped its wings, and went soaring across the field. Its medium size and black-and-white banded tail identified it as a broad-winged hawk; I had seen one a few days earlier in the woods nearby, where I figured a pair might have built a nest. Perhaps the broadwing had been watching the mowed path for incautious rodents and snakes.

As I strolled down the path, I thought of what I had done to renew and maintain this opening at the forests edge.

In 2003, my wife and I and our son moved from central Pennsylvania to an old farm in northeastern Vermont, a region of the state known as the Northeast Kingdom. The Butternut Farm had been named for the many butternut trees growing there. The house was rundown but fixable. The big attraction for us was the land: 120 acres, most of it forested but with several fields totaling around 16 acres. We could cut firewood in the woods to heat the house and make hay in the fields for our horses.

The property also included two old fields that, through the process of natural forest succession, were well on their way to becoming woods. Each field was about two acres. One field lay at a low elevation, behind and below the house; the other was higher up, at the base of a wooded hillside. One of our new neighbors told us that when he started farming in the early 1980s, he cut hay in both fields but eventually gave that up as the fields, left unfertilized, produced less grass and more weeds. As the years passed, shrubs and small trees seeded in.

After we finished remodeling the house (actually, after we pretty much rebuilt it around the dwellings original post-and-beam structure), I turned my attention to the two old fields. When exploring the rest of our land and looking at neighboring properties, I had discovered that most of the area was either forest of varying ages or open hayfields. There were few old fallow fields. Restoring and perpetuating those two old fields would add to the diversity of habitats in our area, something that would be good for wildlife. It would be good for us, because we like to see wildlife. Delaying the task would only make it harder since the trees that had come in were getting bigger every year. As a bonus, removing the trees from the upper field would restore a long-range view to the north and east. Thats where I started working.

Red maples, black cherries, white ash, and quaking aspens had risen above the weeds and grass in the old field. The largest of the saplings were around 25 feet tall. Scattered among the young trees were several dozen thornapple shrubs and wild apple treesI didnt know how many there were until Id crisscrossed the field several times tying bright orange flagging to their crowns. I planned to save the thornapples and apple trees since their fruits are relished by wildlife.

Using a chainsaw, I began felling the hardwood trees. Some of them hung up in their neighbors crowns, and I had to push and pull until they came down, or, working from the bottom up, cut their trunks into stove-length pieces. I dragged the smaller branches out of the field and into the woods. It was hard labor but also satisfying, as I could see progress after each work session.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.