FOR DOUG, sous-chef nonpareil

Twenty-five years ago, in an old house in Berkeley, California, some of my friends and I founded a restaurant we named Chez Panisse. We were driven by a vision of ideal meals prepared from the very best ingredients obtainable, a vision shaped by my experience as a young student in France, where, for the first time in my life, I had seen ordinary people shopping, cooking, and eating as if these activities mattered a great deal more than they seemed to in the suburban America where I had grown up. For my French friends, decisions about food were enormously important; and all around us there were exciting decisions to be made: small, artisanal bakeries and serious butchers and charcuteries could still be found in almost every neighborhood; restaurants maintained a quality of service and cooking that was deeply rooted in a tradition of fresh, seasonal food; and, most of all, in 8 cities and towns throughout France people shopped at marketplaces where local produce could be bought directly from its producers.

Back in the supermarkets of California, I despaired of ever finding the same immediacy and aliveness in the food. But we were persistent and gradually expanded our horizons, successfully locating more and more small-scale, local organic farmers and ranchers whose products, at their best, are entirely the equal of the fresh fruits and vegetables I remember from France. Although we were not alone in gravitating toward such purveyors, I like to think that we helped contribute to the creation of a critical mass of consumers hungry for pure and fresh food straight from the source, because there is now a thriving farmers market in Berkeley, where many of the same farms we buy from have stands.

To my way of thinking, the proliferation of farmers markets is the single most important and heartening development in this country in my lifetime. Janet Fletcher explains why in this book: farmers markets bring us the greatest variety of the freshest, tastiest, and most beautiful food there is, food that is neither wastefully packaged, cosmetically waxed, nor irradiated; they bring us the greatest variety and let us taste before we buy; they protect the local environment by sustaining and restoring greenbelts around our cities; and, above all, they build real community by fostering economic and social ties between producers and consumers and by reacquainting us with the agrarian virtues that were once at the heart of our democracy.

In his recent impassioned defense of farming, Fields without Dreams, the farmer and classicist Victor Davis Hanson dismisses farmers markets as the agricultural equivalents of petting zoos and theme parks (although he does concede that genuine agrarians may be found there). It is true that shopping at farmers markets cannot alone reverse the decline of family farming, but surely the more we insist on patronizing such markets and the more our diet consists of the food we buy there, the more we will increase the demand for the fruits of a healthier, more humane agriculture.

This book is a straightforward, commonsense, and reliable introduction to the market, and it will guide you in the kitchen, too. Janet cooked at Chez Panisse in the 1980s. Based on the evidence of these pages, her thoroughness, efficiency and exuberance in the kitchen are all intact. Like me, Janet believes that the most important stylistic element of cooking is always the quality of the ingredients. With her, I hope this book will send you immediately to your farmers market, willing and eager to let the farmers market determine what you are going to cook.

ALICE WATERS

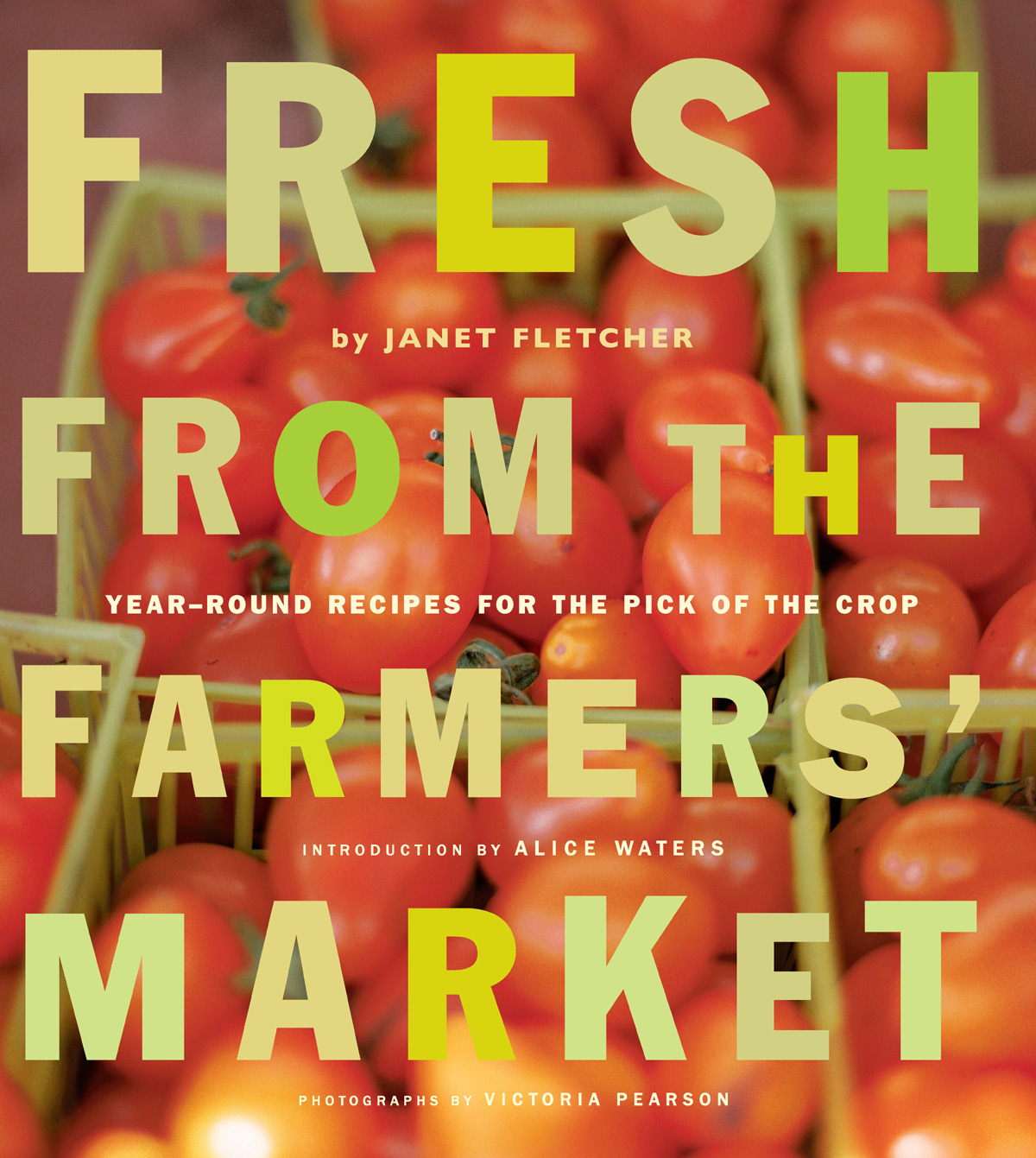

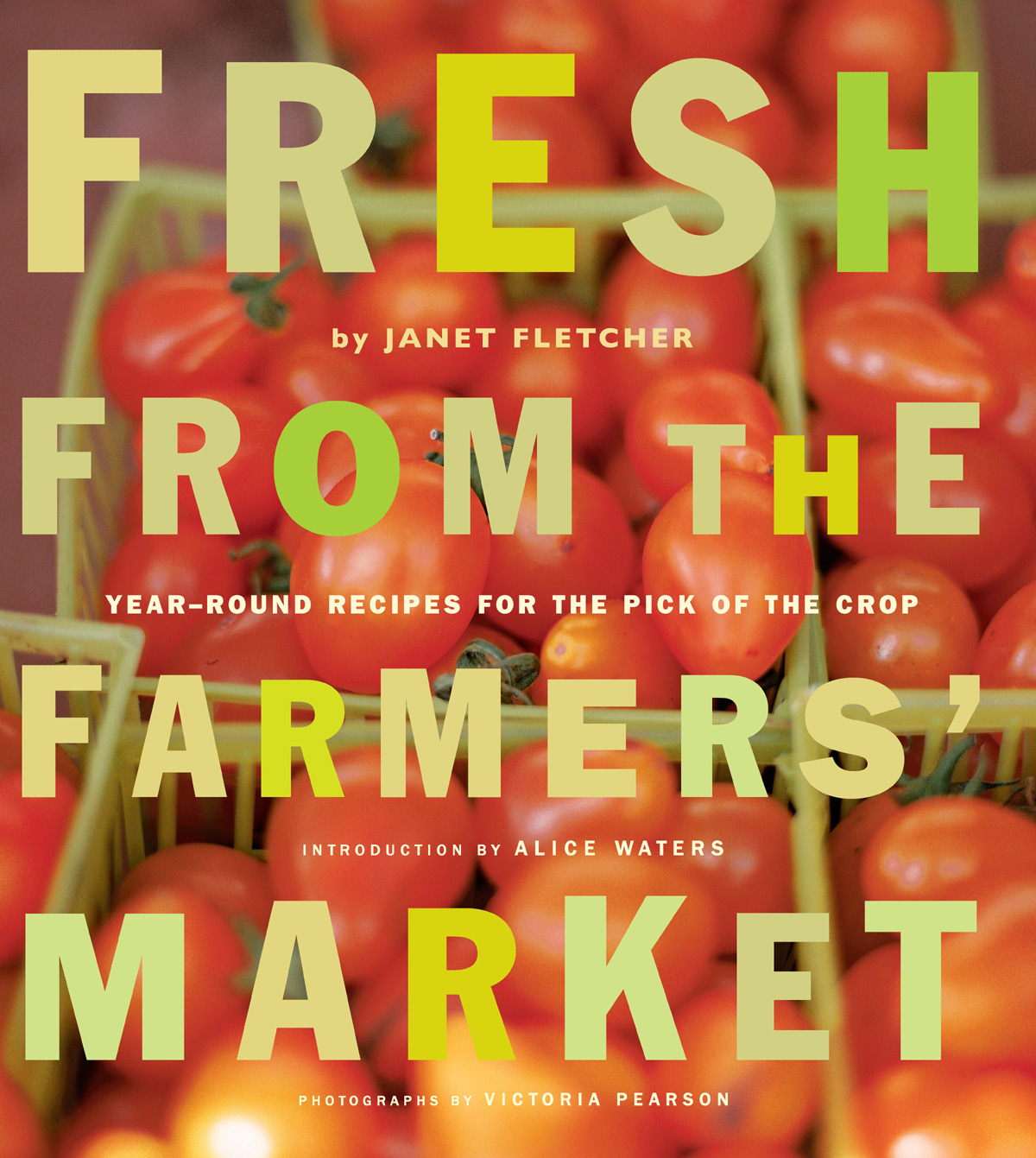

Every Saturday morning in summer, several thousand people do their food shopping at a lively farmers market on the San Francisco waterfront. They sample juicy local peaches, sniff plump blackberries, compare the merits of vendors vine-ripe tomatoes and watch in delight as a farmer peels back the husk on an ear of white corn to show its perfection. Eventually they head back to their home kitchens, canvas bags and willow baskets bulging with peak-season produce.

Around the country, similar scenes play out each week at the nations nearly two thousand farmers markets. Tired of mass-produced food and sterile supermarket settings, more people are discovering the pleasure of buying direct from the grower. Farmers markets have grown exponentially in the last decade, a reflection of the publics desire for food that is fresher, tastier and possibly safer. City dwellers have seen markets revitalize downtowns and build an old-fashioned sense of community in urban areas. For customers of Manhattans Greenmarkets or the Marin County, California, twice-weekly market, shopping is a weekend highlight.

In some parts of the nation, the markets stay open year-round, changing aspect with the changing seasons. The vivid yellows, reds and greens of summer give way to burgundy, forest green and burnt orange in autumn as the market fills with butternut and acorn squashes, persimmons and apples. In winters white light, farmers with mitten-covered hands sell rutabagas and parsnips, wild mushrooms, broccoli rabe and thick, sturdy bouquets of kale and collards. Spring paints the market green, the farmers booths filling with asparagus, artichokes, leeks, peas, fava beans and herbs.

The advantages of shopping at a farmers market are clear to anyone who visits one regularly. Other shoppers motivations may differ, but I can tell you why I prefer to spend my food dollars at a farmers market.

In my experience, you cant find fresher food unless you grow it yourself. Many growers harvest for a farmers market the day before, even hours before. In contrast, produce intended for the supermarket often goes to a packing shed first; then its trucked to a broker or wholesaler, then to the supermarkets warehouse before it ever makes it to the retail produce department. One government study estimates that the nations fruits and vegetables travel an average of 1,300 miles before reaching the consumer.

If you care about quality and nutrition, freshness matters. In the hours and days after harvest, produce undergoes change, almost all undesirable. Immediately, moisture begins to evaporate. Cucumbers lose their crisp crunch; basil wilts; peppers and eggplants start to shrivel. Decay sets in, especially on delicate banded produce like lettuce and spinach. And natural sugars in some vegetables begin converting to starch, which is why peas, beets, corn and carrots never taste sweeter than the day theyre picked.

Nutrients also dissipate quickly. Broccoli loses 34 percent of its vitamin C in just two days. Asparagus making the refrigerated trek from California to New York arrives with only about one-third of its initial vitamin C.

Growers who sell to supermarkets cant do anything about the nutrients, but some do try to combat moisture loss: they wax the produce. Waxes on cucumbers, peppers, rutabagas, melons, citrus, apples and other fruits and vegetables keep moisture in and give the produce a shiny appearance. According to Bryan Jay Bashin, writing in the magazine Harrowsmith, the wax is sometimes mixed with fungicides and sprouting inhibitors before its applied. The only ways to get rid of it are to scrub your vegetables with detergent or to peel them, which eliminates even more nutrients. A better solution is to buy from farmers markets, where growers sell their produce too fast to have to bother with waxes.

Whats more, the farmers market offers variety unmatched by the supermarket. In season, I may find 20 different tomato varieties among the growers at a farmers market, or a dozen different apples or a half-dozen different cucumbers. Supermarkets value uniformity; farmers markets encourage diversity.

Next page