by the same author

THE MIGHTY NIMROD

A Life of Frederick Courteney Selous

SHAKAS CHILDREN

A History of the Zulu People

LIVINGSTONES TRIBE

A Journey from Zanzibar to the Cape

THE CALIBAN SHORE

The Fate of the Grosvenor Castaways

STORM AND CONQUEST

The Battle for the Indian Ocean, 180810

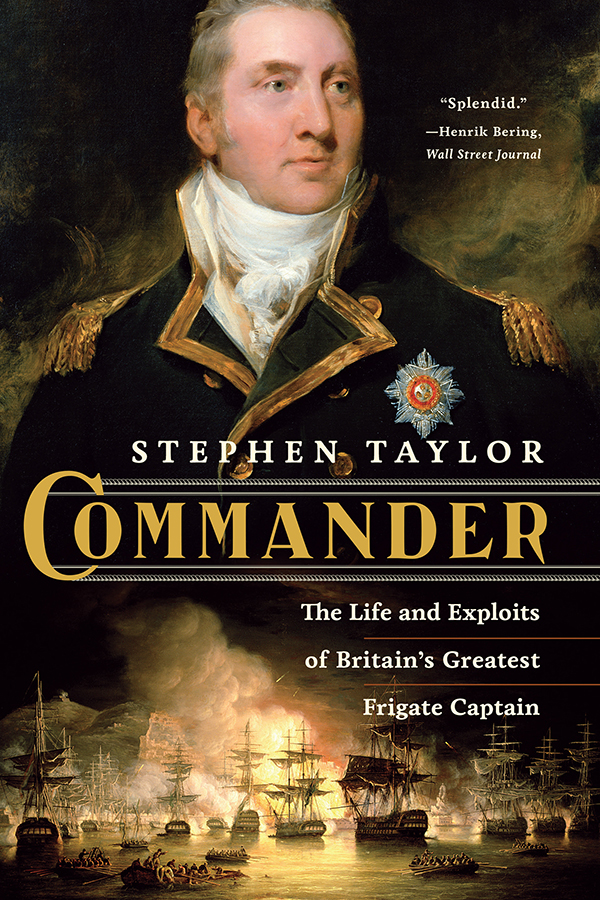

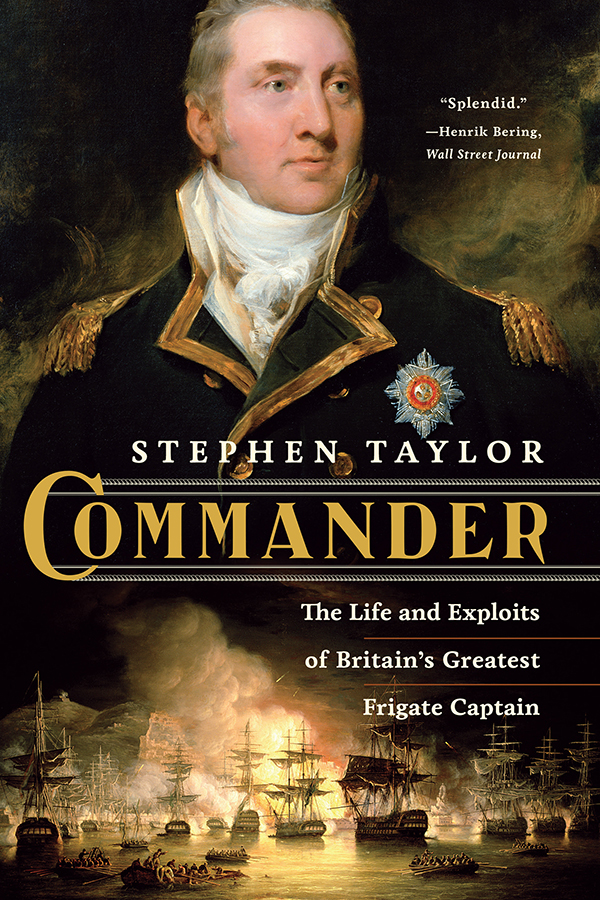

Commander

The Life and Exploits of

Britains Greatest Frigate Captain

STEPHEN TAYLOR

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

To the Memory of My Mother

Contents

Illustrations

Plates

Sir Edward Pellew by Thomas Lawrence

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Fleetwood Pellew in action at Batavia

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

The wreck of the Dutton by Thomas Luny

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Teignmouth by Thomas Luny

Collection of Teignmouth Museum and Historical Society

Destruction of the Droits de lHomme by Ebenezer Colls

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Captain Sir Christopher Cole by Margaret Sarah Carpenter

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Troubridge by William Beechey

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

The bombardment of Algiers by George Chambers

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Vice-Admiral Sir Richard Keats by John Jackson

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Viscount Exmouth, by Samuel Drummond

Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, UK

Edward Pellews seas of endeavour: the Channel, Biscay and Mediterranean.

Introduction

Sea officers pose a more than usually daunting prospect to the biographer. Though we may be drawn to maritime subjects by the grandeur of the sea and the drama of life on it, the technicalities of sail are a challenge to both writer and reader, while the blue-coated personalities who commanded tall ships can appear leaden obscured by nautical jargon and a milieu now strange to us. Perhaps for this reason, fiction has been more successful than biography at bringing such men to life; the name of Hornblower is probably recognised by more general readers than that of Hawke, Aubrey more than Anson. Nelson, as in all things, is the exception, but that is because Nelson represents themes seemingly bigger than even the sea transfiguration and martyrdom, not to mention sex and scandal.

Edward Pellew actually bestrides both worlds as Hornblowers fictional mentor and as captain of the famed Indefatigable ; and if his name is now better known from the novels of C. S. Forester than for his true exploits, these still resonated grandly enough in his own time. Pellew can be fairly described as the greatest frigate captain in the age of sail, an incomparable seaman, ferociously combative yet chivalrous, and with a gift for performing eye-catching feats in public. Later in life he commanded a fleet in a bloody and crusading operation to free European slaves in Barbary.

Yet Pellew is a neglected figure, even in the somewhat rarefied field of naval studies. Despite the wealth of available material, his paradoxical spirit pugnacious but tender, acquisitive yet generous may have stood in the way of biographers. While they have extolled the doings of Pellew the commander, they seemed to me as I started to explore his life, to have missed much of Pellew the man.

I should admit to having been initially drawn more to the man than the commander. In studying his letters for my last book, Storm and Conquest , I was struck by their warmth. While his education was scanty and his hand so atrocious it can defy transcription, they have an intimacy and a sensibility that are strikingly modern. His love for his men, as well as his friends and fellow officers, was as transparent as his desire for glory and honour. His nature, like his courage, had nothing to do with English sangfroid. It was hot-blooded, elemental. Throughout a long life he campaigned on behalf of individuals he saw as victims of injustice.

His flaws were of a part with this emotional temperament. Left fatherless at the age of eight, with a mother and five siblings, Pellew fought his way from the very bottom of the Navy to the top, and then covered the tracks of his rise from penniless youth to fleet command and a viscountcy. But the scars of childhood distress were never erased and he pursued wealth almost as avidly as he did an enemy frigate. Although there was nothing unusual in this, Pellews awkwardness on top of his impoverished origins he was a clannish Cornishman attracted the wrong kind of attention. He had none of Nelsons gift for effortless politicking and, as an outsider with a talent for antagonising his better-born peers, he made many foes. Another boyhood legacy was a fierce protectiveness of his younger brother, a fellow officer whose fallibility he helped to conceal, just as he promoted his sons careers well beyond their abilities. In any matter of family, Pellew was blindly and dangerously partisan.

There are two previous biographies. The first was commissioned by his elder brother as an exercise in reflected glory soon after Pellews death and published in 1835 in defiance of his beloved wife Susan who denied its author, Edward Osler, access to his papers. Although pure hagiography, the book divided the family. Pellews most devoted son, George, scrawled objections on virtually every page, inserting corrections and observations gleaned from Pellews confidant and right-hand man, John Gaze. He then spent years transcribing his fathers papers and making notes for an approved biographer.

Almost a century passed without one being found. Eventually Pellews descendants passed his papers to the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich on the understanding that its director, Geoffrey Callender, would write the new, long-awaited life. Callender, however, was overworked and passed the task to a promising if opinionated graduate, Cyril Northcote Parkinson, just starting a career as a maritime historian. Within a year Parkinson produced a substantial book, Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth , which was published in 1934 and has remained the standard work.

Parkinson had a prodigious intellect though he is remembered today more for the aphorism of Parkinsons Law than his contribution to maritime studies but the life of Pellew, his first foray as an author, was far from his best work. Written in haste, it is wordy, condescending (particularly considering that it came from the pen of a 23-year-old) and simply wrong in some respects, notably in underestimating the difficulty of Pellews early years, his attitude to discipline and the nature of the resentment for which he became a target.

The materials for a reappraisal are extensive. The Exmouth papers at Greenwich alone run to thirty-three boxes, each containing hundreds of letters, left in the order in which Parkinson examined them eighty years ago and uncatalogued until recently. The Admiralty Records, the logs and musters of Pellews ships, were ignored by Parkinson but give insights into Pellews methods. The papers of his friends and enemies, scattered in archives around the country, illuminate the jealousies and feuds that dogged him.

Next page