Contents

Landmarks

Page List

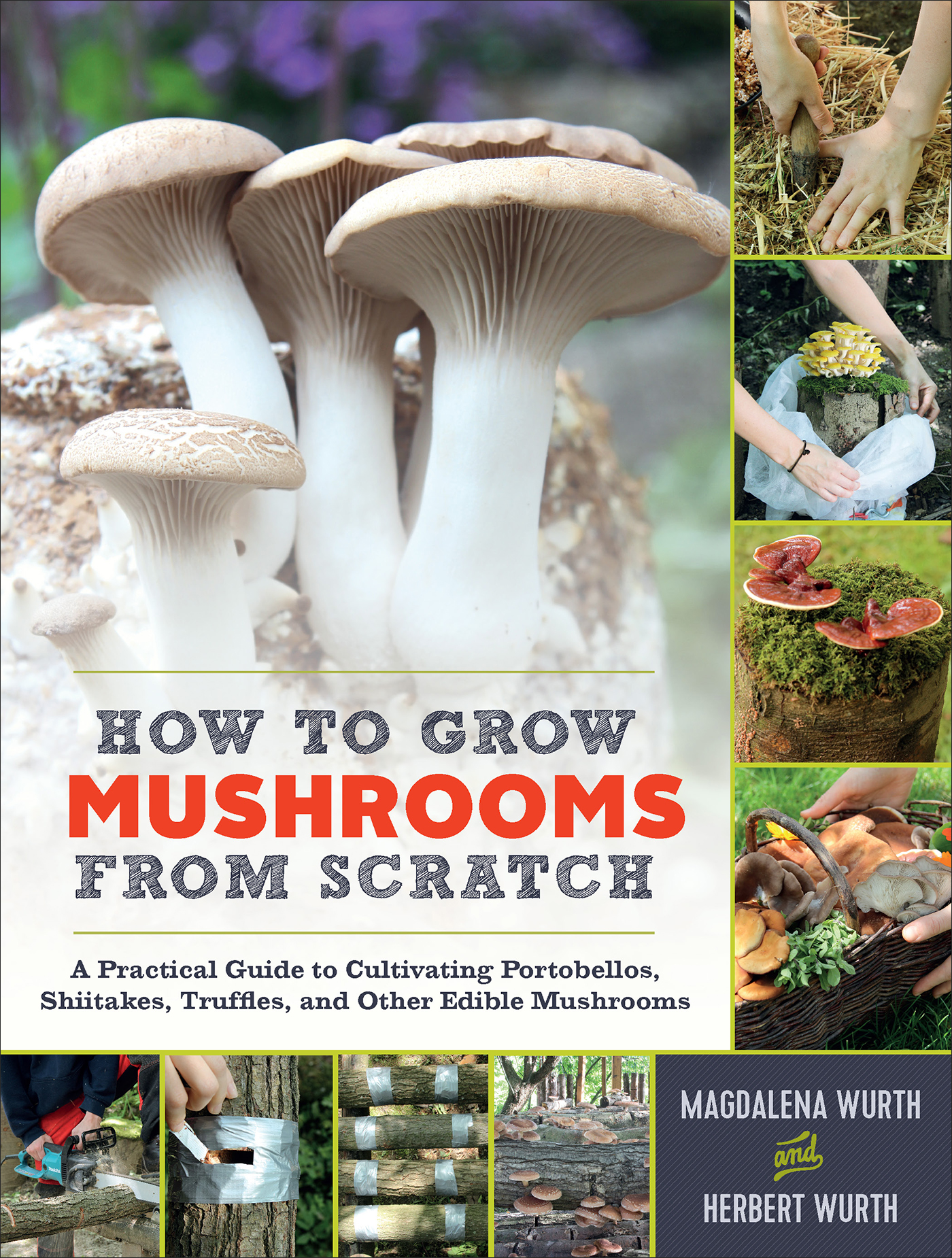

The Origins of Our Mushroom Garden

I spent a lot of time in the forest as a child, and even back then, mushroom hunting was a family tradition. Later, as I began my professional life as a chemist, I worked together with collaborators at TU Wien, the Vienna University of Technology, on a fascinating project that involved fungi that break down cellulose for the further processing of agricultural by-products. Because it involved similar methodologies as this project, cultivating mushrooms at home suddenly seemed very accessible. In those early years, commercial mushroom spawn was hard to come by, a situation that turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Over the years we accumulated a lot of experience in the fields of microbiology, mushroom spawn production, and the cultivation of edible mushrooms on myriad substrates. By 1984 we had inoculated 100 straw bales with king stropharia mushroom. More recently we have been focusing our efforts on cultivating and breeding edible mushrooms on logs, and we grow our shiitake mushrooms by emulating the traditional Japanese method.

Herbert and Magdalena Wurth

Photo: Benedikt Wurth

Twenty-five years ago we relocated and thus had the opportunity to establish a new mushroom garden and gain valuable experience in design. Through our cooperation with Arche Noah, we noticed great interest from gardeners in cultivating edible mushrooms using natural methods. Personally, Im most interested in the challenges presented by more difficult to cultivate mushrooms like reishi. Working with fungi has allowed for profound insights into the inner secrets of these fascinating organisms.

We have a family-owned business in Austria, the Waldviertler Pilzgarten. Were excited about the continuing development and implementation of new ideas in the field of fungiculture. We hope you will see this book as an opportunity to start growing edible mushrooms in your garden, cellar, or courtyard, on your patio or balcony, or even in the kitchen.

Herbert Wurth

Harvested mushrooms ready to cook and eat

Introduction: The World of Mushrooms

What are Fungi?

Fungi have no chlorophyl within their cells. Unlike most plants, they do not use photosynthesis to produce energy. Fungi have developed a fascinatingly large number of methods of obtaining nutrients, each characteristic of individual species.

Many species are saprophytes, that is, they feed off dead organic matter. Because they can break down components of wood such as cellulose, saprophytic fungi have an important role in the forest as decomposersthey break down dead wood and other dead plant material into simple organic compounds. Humus is thus created. So wood, straw, or compost are often used as growing media when cultivating edible mushrooms.

Saprophytes can be placed into two groupsprimary and secondary decomposers:

The former are fungi that are able to break down an unaltered raw growing medium. Examples of this group include oyster mushrooms and sheathed woodtuft.

Secondary decomposers, by contrast, require that their nutritional basis first be macerated by microorganisms. Button mushrooms and shaggy mane are included in this group.

Another group of fungi live parasitically. These species can be especially problematic in the fields of agriculture and silviculture, as in the case of honey fungus (Armillaria spp.), which is common in trees and woody shrubs. Parasitic fungi can also infect living (often already weakened) organisms and sap them of energy and nutrients.

The third group of fungi are the mycorrhizae, including, for example, burgundy truffle (Tuber aestivum var. uncinatum), porcini, and chanterelles. The word mycorrhiza comes from the Greek words mykos (fungus) and riza (root). We distinguish between three types:

Ectotrophic mycorrhizae attach themselves to the surface of the roots of certain higher plants.

Endotrophic mycorrhizae are widely distributed and have the ability to integrate their hyphae into root and bark cells.

Ectendomycorrhizae bridge the gap between the two groups described above. Likewise these live in symbiosis with plants.

Plants and fungi both benefit from this partnership. A fine, practically invisible network of fungal hyphae encases the roots of plants and solubilizes nutrients for them. In return, the plants supply the fungi with carbohydrates (sugar). The plants root system increases in effective size, which increases its capacity to take up nutrients and water. Such partnerships between fungi and plants are complex and in many cases have yet to be researched. This is also the reason for the low success rate in cultivating wild fungi such as porcini and chanterelles. Experiments with mycorrhizal fungi have often pointed to the conclusion that cultivation without a symbiotic partner is impossible. One of the few examples of successful mycorrhiza cultivation are truffles. Incidentally, a symbiotic mycorrhizal partner is also a requirement in orchid breeding.

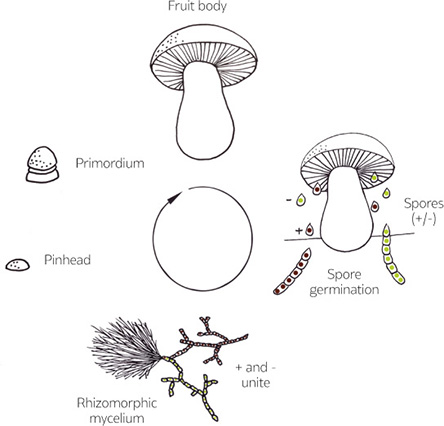

Structure and life cycle

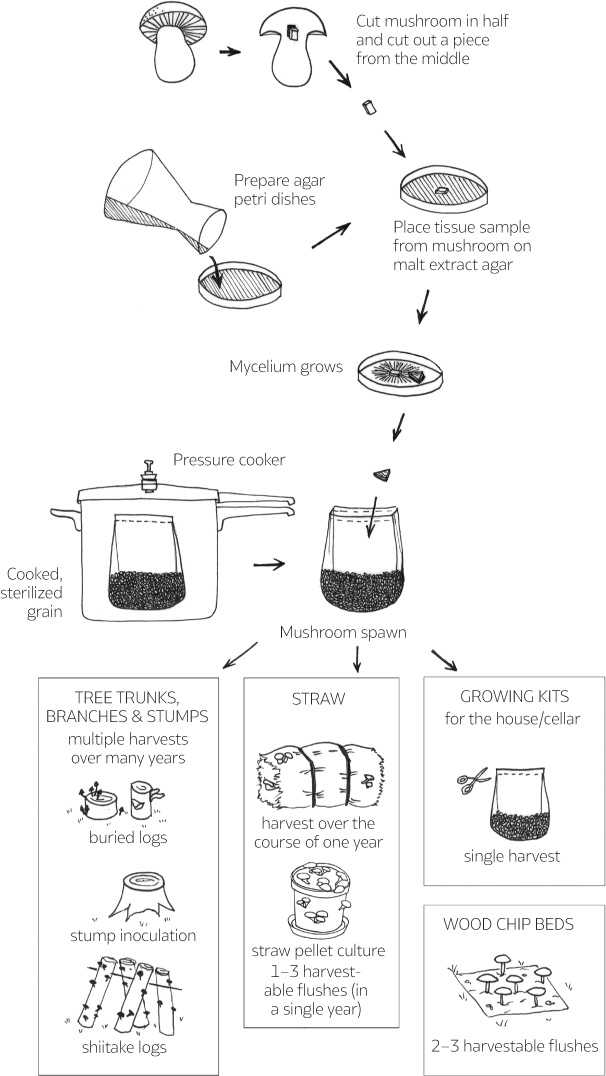

An overview of mushroom cultivation

The authors mushroom garden

Structure and Life Cycle of a Mushroom

When we talk about mushrooms, we mean the above-ground fruit body of the larger fungus organism. Indeed, the entire organism consists of far more than just the familiar cap, gills, and stem of the fruit body; it is mostly the mycelium that grows underground. Mycelium is made up of hyphae, which are somewhat like the fine root hairs on tree roots. Still, the outward appearance of the mushroom is an important distinguishing feature of fungi.

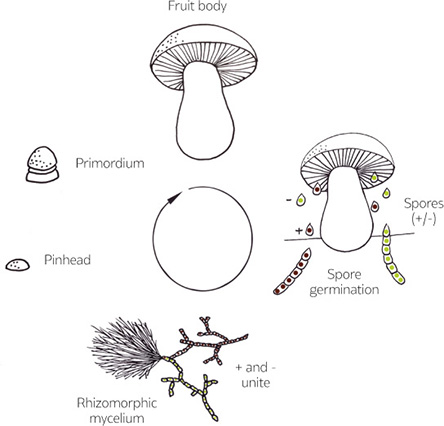

Spores, which are somewhat analogous to the seeds of plants, are produced and found in the gills, ridges, teeth, or pores of edible and medicinal mushrooms. They are microscopically small and, at the appropriate moment of the fungus development cycle, are disbursed into the surrounding area, often with the help of wind, water, or other organisms. Positively (+) and negatively (-) polarized spores germinate when they meet under favorable environmental conditions in a suitable substrate. Hyphae then proliferate and rhizomorphic mycelium is created. As development continues, dense networks of mycelia form, upon which nodules called primordia develop, from which mushrooms eventually emerge. Mushroom emergence represents the completion of the fungal life cycle, which can now begin anew.

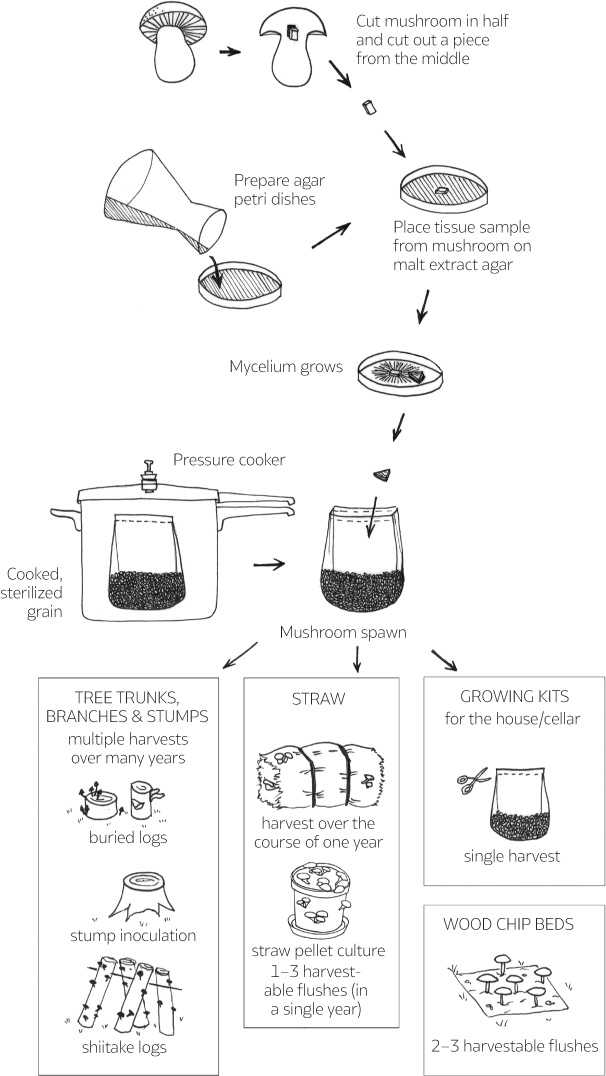

An Overview of Mushroom Propagation