My Dear Boy

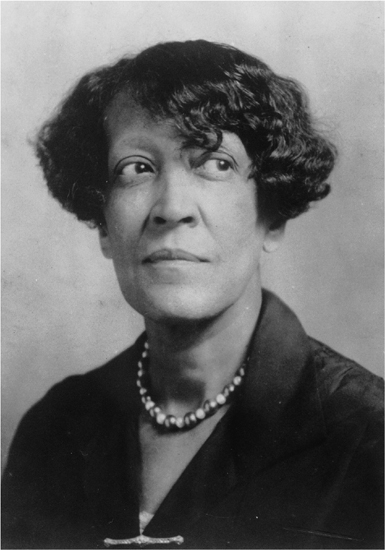

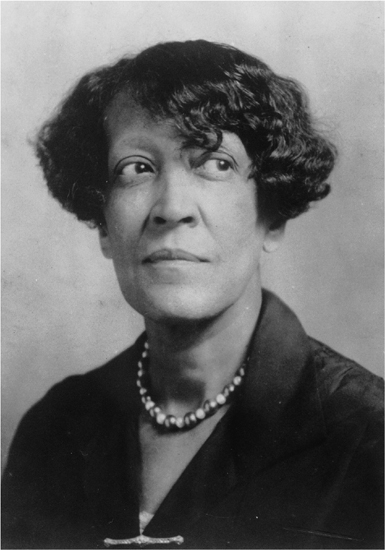

Portrait of Carolyn ClarkCaroline Langston Hughes Clark. Printed by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated. Copyright 2013 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

My Dear Boy

CARRIE HUGHESS LETTERS TO LANGSTON HUGHES, 19261938

Edited by

Carmaletta M. Williams

and John Edgar Tidwell

The letters written by Carrie Hughes are printed by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated. Copyright 2013 by the Estate of Langston Hughes.

2013 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Set in 11.5/15 Adobe Garamond Pro

Printed and bound by

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for

permanence and durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 13 c 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hughes, Carrie, 1938.

[Correspondence. Selections]

My dear boy : Carrie Hughess letters to Langston Hughes, 19261938 / edited by

Carmaletta M. Williams and John Edgar Tidwell.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-4565-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8203-4565-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Hughes, Carrie, 1938Correspondence. 2. Hughes, Langston, 19021967 Correspondence. 3. Mothers of authorsUnited StatesCorrespondence.

4. African American mothersBiography. 5. African American authorsFamily relationships. I. Williams, Carmaletta M., [birth] editor. II. Tidwell, John Edgar, editor. III. Title. IV. Title: Carrie Hughess letters to Langston Hughes, 19261938.

PS3515.U274Z48 2013

818.5209dc23

2013003511

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN for digital edition: 978-0-8203-4639-7

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO

Our Dear Mothers

The Late Doris Rebecca Grant

The Late Verlean L. Tidwell

AND

Our Dear Boys

Dwight Chief Williams

Jason John Williams

Nicholas A. Elias

Levert Tidwell

FOLLOWING LANGSTON

A Foreword

Late summer 1967. Sumter, South Carolina. Jet magazine has just arrived as it does each and every month. Mama sits in her chair reading through the current Black history news, holding the tiny Jet pages by their corners and reading aloud in her most operatic voice. She includes in her reading news of any deaths she believes should matter to us children, whether we recognize the names called out or not. She wants us to know that both things and people come and go. Mama and Daddy are lifetime members of the NAACP. They believe in supporting Black cultural institutions. They treat Black publications like modern-day North Stars. Jet, Ebony, The Crisis all arrive and take their proper place on the main coffee table like Black constellationsshining up at us. Until we can read for ourselves, we are read to every day of our young lives. I learn very early that there are Black people who must never be forgotten.

James Mercer Langston Hughes died when I was ten years old. The facts were surely read aloud: Joplin. Grandmother. Kansas. Class Poet. Dream. Harlem. Jazz. Race Pride. Mama called him a poet of note, reminding me that I had recited some of his poetry once, A Dream Deferred and The Negro Speaks of Rivers, at Emmanuel Methodist Church for Black History Month. I do not remember this moment as much as I have been reminded of this moment.

Langston Hughes followed me around like a great light. In my neighborhood Langston Hughes was called some variation of the Poet Laureate of the Negro Race. For mehe was exactly that. As a young Black girl of the segregated, then begrudgingly integrated South, he might as well have been the first poet of the whole wide world.

In seventh grade, I started keeping a journal and writing poetry. It would be several years before I would read somewhere, and marvel, that Langston Hughes had been the class poet of his own eighth grade. The Crisis magazine that kept arriving long after Hughes was dead was one of the places I began to check the pages oflooking for more from Langston Hughess many worlds: essays, librettos, plays, autobiography, childrens books, jazz histories, solo poems especially. Long after Langston had gone there were other things that kept him alive in me: reading The Big Sea and The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain in college, finding Fire!! in the Schomburg stacks one summer between graduate school sessions. I followed the life and work of Langston Hughes from discovery to study. I never knew quite where his bright words might lead me. I just knew I had to walk strong into the light.

I was a curiously sensitive, indeed sometimes melancholy Black girl living in the Civil Rights South. I belonged to the wide wicked world of the South yet I wanted to know more than anyone seemed to want to tell me. I listened to Daddys jazz records and wanted more. I listened to Mama read about the Black world out and beyond and wanted to know more. I had questions about the physics of life: Who got to move through the world with their head up all effortless and easy? Who had perfected the act of walking while bowed and bent and looking down? Who got to etch their initials into things like silver cups and write letters on cotton paper made with silk thread? Who wrote and hid their stories on paper bags and napkins? Who only had time to wash and wax? Who had to move on through the world with a sack of sorrow on their shoulders? Who got to dance and be the movie star? Who always died younger with the expected broken heart?

During my search for how to become the poet that I didnt know how to become, the poetry and life of Langston Hughes guided me from all four directions of the universe. I found in James Langston Hughess life a horizon line, a clear pathstepping stones to get from here to there. Here was a poet born and raised in another small town in Americajust like me, from a politically charged familyjust like me. A poet raised primarily by his grandmother, who had instilled in him an everlasting sense of race pridejust like me. Here was a poet who had found velocity in books and paper, who had been the class poet at a young age, who wrote dutifully and prolifically from that childhood forward, a poet who had found his way to a historically Black college, who kept honing his Afrocentric landscapes and portraits. Hughes was a poet who jumped freighters and wrote about laziness and labor, who left home and couldnt always be what his mama or his daddy or his people wished, but nevertheless wrote proudly all the way to the end, as a Negro artist. All along the way Langston Hughes picked up and moved mountains aroundinside one little Black girl born in the segregated, now integrated South, who held pencils as close as if they were candy canes. Langston Hughes was a blazing light in my wilderness.

Hughess deep love of his own Blackness, in a world that suggested he be less Black or more anything else, situated me. Langston Hughess deep love for his Blackness and his primal dedication to say the hard thing with great visual verve, unmasked the persnickety literary world with its constant and great warnings about color lines and political stop signs. Langston Hughes was unbowed. He wrote tirelessly about his affection for Black people. Black people were his study and his course in life. Through the prism of his pen, Langston Hughes taught me that Blackness held everything under the sun.

Next page